According to the latest data, Chinese students in the UK are experiencing high levels of anxiety and insecurity during the pandemic. Why has the situation been more difficult for them?

Hey mom, how’s your day, says Paige, a graduate student majoring in linguistics. She had taken a deep breath and arranged her facial expressions before she picked up her mobile to Facetime with her mother in China. During the twenty-minute conversation, she occasionally dodges from the screen, stealthily wipes away tears and puts on a smile again.

Everything is super great, don’t worry about me, said Paige to her mother, but actually thought: I don’t want to live anymore.

Such scenes occur almost every time she Facetimes with her parents. “We all tell lies,” said Paige. “The old proverb ‘report good news rather than suffering’ is the tacit understanding of all Chinese international students.” In fact, she lost interest in life altogether for more than three months and was diagnosed with moderate depression by the National Health Service (NHS) two weeks ago.

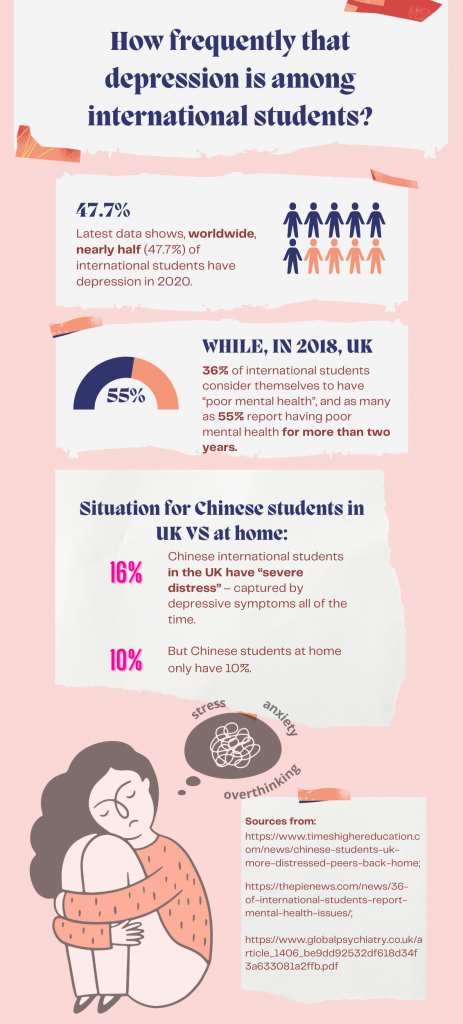

Everyone in the UK has been struggling with their mental health over the last 12 months. A report by the country’s National Statistics Agency says that depression rates have doubled since the COVID-19 pandemic began. For Chinese students who are far from home, the situation is even worse. According to the latest research, Chinese nationals at Western universities are experiencing alarmingly high rates of anxiety, depression and other mental health issues compared to local students.

Academic pressure is one of them.

“If I can’t get into UCL, my parents won’t pay for my further study,” said Jin, an undergraduate student from the University of Liverpool majoring in architecture. “This year, our education is entirely online anyway. Staying at home, I can at least avoid paying rent. My family has already sold a house to pay for my study, and I don’t want to disappoint them.”

From Kunming, Yunnan, a third-tier city in southwest China that borders Vietnam and Laos, Jin’s own pursuits and his parents’ expectations brought him to the North of England, 8,000 kilometres away from home. There, he is hoping to get the chance to have a better platform from which to succeed. But being stuck in a room with heavy academic pressure made him fall into a vicious circle. “The more anxious the more I want to go out and relax, the more I can’t, the more anxious I am,” said Jin.

In order to get good grades in his final year and enter his dream university, he stayed up late at night or studied all night. But anxiety got him. “I wake up in my sleep and tremble all over. I often feel that life is hopeless. But I don’t tell my parents and friends that as it would be too shameful,” said Jin.

The population of Chinese students who refuse to go to the doctor because of the same concerns as Jin is much bigger than the public data realized. As a student studying in the UK for three years myself, every semester I’ve had countless conversations with students who have been struggling with the cultural stigma of mental health problems. Like Paige and Jin, a number of them wear brave faces but actually may have dangerous consequences if they do not take action.

In March 2017, Miss Wang, a Chinese graduate student on accounting and financial management course at Lancaster University hung herself in her room while suffering from a major depressive disorder caused by the academic pressure that she imposed on herself. Nevertheless, as reported by the Daily Mail, what really drove her to her death was the underlying concept that anyone with a mental health problem who goes into hospital or takes medication ultimately brings shame to their parents. She refused to take medicines nor would she inform her parents, and she also refused to talk to university staff.

The idea is deep-rooted in traditional Chinese attitudes that mental health issues equate to being insane and mental health patients are a source of humiliation and unspeakable, rather than suffering in such a way being as normal as dealing with a bad case of flu. This makes it much more difficult for Chinese students to break through their imprisoning perspective on the matter and face up to their mental health problems.

But for the students who took that brave step forward did not get the empathy they had hoped for either. “I was even more helpless and wronged than before,” said Paige. She had called the student support centre to talk about her academic pressure and discrimination that made her feel depressed and hurt, but the staff just told her that racists were in the minority and do not take it too seriously.

“How can she make light of the fact? She is not the ones who are alone in a foreign country, studying and living independently without friends and being verbally abused,” said Paige. Under a series of pressure and challenges, her emotional wall finally collapsed when she was not understood.

“Being able to be in a space with people who would completely understand you without having to explain what your experiences like is very validating,” said Aashfeen Kamal, a member of staff from the Conscious: The Edinburgh Mental Health Charity Ball, which is a famous entirely student-led registered charity since 2019.

“Talking to people who have the same cultural background as you can make people feel a sense of belonging, which is what international students must lack. For people with mental health in a foreign country, this will give them hope,” said Aashfeen.

Last year, she created and ran a Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME), support group, giving students a secret base where they can relax and talk about their thoughts and experiences. The most important thing is to give them enough respect and understanding and to actively provide them with suggestions as well as follow up on the students’ current respective situations.

“It would be so much better if I made friends who respected me,” said Yujie Wang. “Interpersonal relationships are the cause of my pain.”

Far from the vast Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in northern China to Southampton, the southernmost city in the UK, her loneliness is not only because of the foreigner identity or the isolation of being trapped in their room since the lockdown but the limitation of social relationship choice.

“I can’t fit into other people’s social circles at all, but because of the Covid, especially after the lockdown, it’s hard to meet new people even if you find out that the people you are not good with,” said Yujie.

Yujie was fully focused on her studies plan before going to the UK but did not seriously consider her choice of accommodation and roommates. “This is the most regretted thing I did and directly led to my depression,” said Yujie.

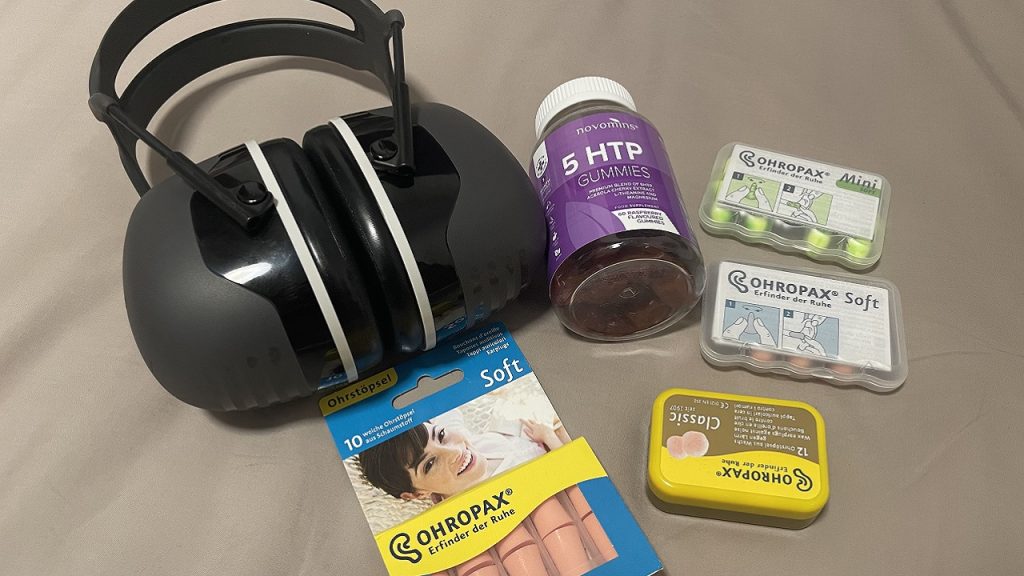

The continuous talking and occasional yelling coming from next door at four in the morning kept pouring into her ears and shattered her brain. Eventually, she could not help but hold the quilt tightly and burst into tears.

“It would be easy to move a new apartment before Covid, but now I have no choice,” said Yujie. Due to lockdown, all student apartments strictly controlled the flow of students and the hotels were closed.

Nights soaked in tears like this have long been the norm for her. Long-term lack of sleep has also made her restless and collapse emotionally. Extremely trivial things can make her cry hard, and her whole neck and face turn red.

“I’m not me anymore,” said Yujie. Coupled with insomnia she has no motivation to do anything. “Even eating makes me feel extremely tired,” said Yujie, who self-tested a moderate depression online in May, only half a year after she came to the UK.

But their equal communication was directly ignored, and tough conflicts only made her roommate retaliate in disguised form. More than five times Yujie negotiated with her roommate and ended with nothing. Even the reception’s warning can only change for one week’s relative calm, she finally couldn’t bear to quarrel with her when she woke up again wearing earplugs.

“I wore headphones to sleep, but I got acute otitis externa. My ear hurts to death. It happened that during that time I had to rush assessment. Just let me die in place, even make things easier.

“She brought a group of men to a party next to my room the next day, and they laughed loudly from 11 p.m. to 5 a.m.,” said Yujie.

However, according to Yujie, the worst part is the lack of outline – everyone is busy, no one really listens to her. With remote study and isolation, she vents online by starting a forum and meeting new people from her university.

“That comforts me more or less,” said Yujie. “We ranged a chat group and to gathering as many people as we can.”

Being a good listener probably is more important to mental health than anything else, especially in terms of support, said Aashfeen.

“It’s great to have a sense of been support,” said Aashfeen. “We also would invite people to even they didn’t want to talk if they just wanted to listen and experience that was also something you were able to.”

“For a while, I feel that all alone in the foreign land, keep-alive is my biggest task,” said Yujie. “I don’t know how long that would be, but having someone understand me made my life better.”