With the rising cost of studying in the UK, should British universities worry about the loss of Chinese students who contribute massively to their revenue streams?

We talk to people studying in the UK right now to find out whether they would recommend UK university life to their friends back home.

Three months ago, Sun first heard about the private tutorial classes from his classmate.

“The classes were run by the Chinese tutors, the same ones who usually help the professors communicate with the students at school. Every student who attended paid more than one hundred pounds,” Sun said. “The tutorials were about what we learned in school lessons. They would help students summarize the course content and teach you how to deal with the exams specifically, but not cheat.”

Sun did not attend the class because he was concerned about its legality. “These courses don’t seem to be run openly, but behind the scenes.”

But the worries about not passing the exams may have overridden a few students’ concerns about the legality, making them willing to pay extra for tutorial classes even after paying a tuition fee of over £20,000.

“I guess there are probably dozens of people taking the tutorial classes,” Sun said. He is studying for a master’s degree at Cardiff University’s business school and has more than 100 classmates in his course.

About 90% of Sun’s classmates are Chinese, part of the over 144,000 Chinese students studying in UK universities. The majority of them pay double the tuition fees of home students.

According to The Economist, Chinese students make up one-third of the non-EU international students at UK universities and together pay around £2.5 billion each year, accounting for around 6% of overall university income.

Some of them are concentrated in what are called “Oversea students oriented” majors, like Sun’s course. He said: “There’s not much opportunity to interact with other nationalities in the classroom because there are not many foreigners.”

In these majors, some universities provide Chinese or Chinese-speaking tutors, which makes it possible to run extra tutorial classes. And for students, apart from the language barrier, another reason why they pay for it may be that the school’s lessons hugely rely on self-learning skills.

“I would say a lot (of it relies on the self-learning skills). After coming to Cardiff University, the difference I feel from my undergraduate course is that it comes more from my self-study,” Sun said. “I think having reached the postgraduate stage, self-study is something you need to train for.”

“One of the reasons I didn’t go on the tutorial classes was because I felt I could study on my own … I was able to cope with the exams,” Sun said.

Many Chinese students at various British universities feel that the value of their postgraduate courses, for which a high tuition fee is charged, depends on the ability to learn on one’s own. Sun believes this is a skill that postgraduates should have, but some students are seeking more help from their school.

“At the beginning of this semester, my classmate openly stated in class that there were too few class hours, and the tuition fee I paid was not worth it,” said Qiu, a Chinese student from the Edinburgh College of Art. “I believe that many people have the same feeling.”

Due to the pandemic, Qiu’s course was changed from two years to one year, and as a result, most internship opportunities were only offered to undergraduates who had more spare time. However, in the last semester Qiu had only about 10 hours per week of required classes, and with the outbreak of the strike at the University of Edinburgh, more and more free time is becoming available.

“When the strike started, students wrote an email to the school. The school decided to let us find relevant courses online to study on our own and they could offer compensation, but there were only 2,000 places available.” Qiu said.

As well to the small amount of course time, Qiu is uneasy about the teachers’ lax requirements. “We can book the workshops, but it depends on if you want to, there are no requirements. The weekly task is also okay if you don’t finish it. Our teachers are always very gentle when advising on the work and there doesn’t seem to be strict criteria, so I’m not sure how my work is really doing.”

Feng, another student studying Global Journalism at the University of Sheffield, also agrees that self-learning ability determines the value of the course. She said: “Because you still could smoothly graduate even not attend the lessons as long as you finish the assessments. And the course contents don’t seem to have too much to do with the assessments.”

However, although Feng is unsatisfied with the quality of her course, she is enjoying the leisurely life here. Because this was the reason she came to the UK, to get a postgraduate diploma with relative ease, rather than taking part in the increasingly competitive postgraduate entrance exam in China.

“After all, I didn’t expect much from it before I came,” Feng said. “This mindset should be quite common. It feels like most students don’t come to learn anything, but just come to get a diploma and experience life in the UK.”

Due to the recession in the job market, In 2021, more than 4.5 million students took part in the Chinese postgraduate entrance exams, double the number five years ago. Many students will prepare for domestic exams as well as apply to UK universities to make sure that they won’t ultimately nowhere to go after graduation.

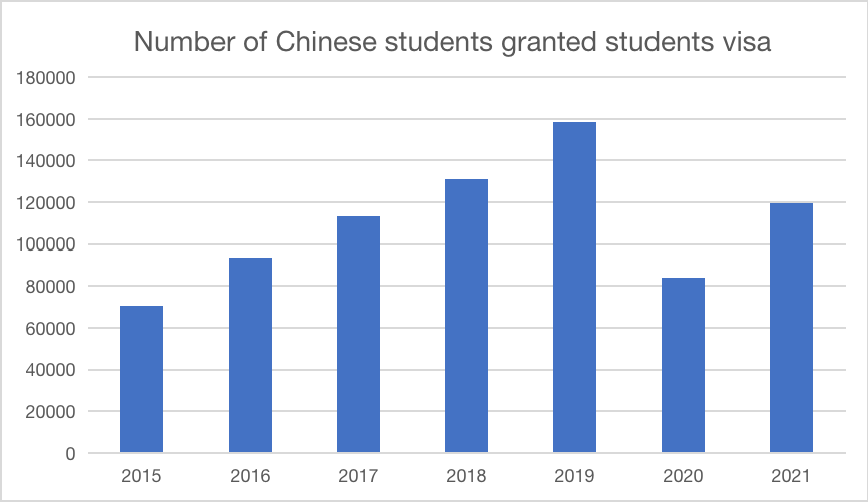

Escaping the cruel competition at home is backing up the steady flow of Chinese students coming to the UK. 2020 saw the first decline in new Chinese students since 2007/08 due to the pandemic, but this finger soon rebounded strongly. More than 28,000 Chinese students applying to UK universities in 2021, 16.6% higher than the previous year and, for the first time in history, more than the total of applicants from EU countries.

For Chinese families willing to pay a higher tuition fee in exchange for a postgraduate degree, studying in the UK remains the preferred option due to the simplicity of entry. Feng said: “I would recommend (others to study in the UK). If you want to save on rent, have fewer things to do, and convenient transportation, then you come. It’s especially good for people who want to experience a happy life.”

However, for students from a modest financial background rather than the stereotypical wealthy Chinese families, with flights from the UK to China rising from £600 to £6,000, such a deal is increasingly not worth it. Qiu is one of the students who think so.

“A postgraduate degree will definitely help you get into better companies. But now, many companies are focusing on undergraduate degrees. My Chinese classmate who studied in Edinburgh was brushed off for Tiktok’s company because his undergraduate degree wasn’t from a first level Chinese university,” said Qiu.

Another student, Chen, gave up his plans to study in the UK last year. He said: “Human Resources are also aware that the threshold for studying in the UK universities is lower than do postgraduate studies in China. It’s easier for recruiters to know information about universities in China, but UK universities not, so they are not sure how much the student has learned.”

As British universities’ diplomas become less recognised, many students are thinking of moving to other countries. Qide, one of China’s largest study abroad consultancies, reported a 126% increase in enquiries about studying in Hong Kong. While the UK remains the most popular destination, its share has been declining.

“You feel that there’s not much point in taking classes here, but the diploma seems to work a bit, but then when the society starts to question the value of master’s degree from UK universities, it’s useless again,” Qiu said. “I wouldn’t recommend coming to the UK to anyone else because how much you learn really depends on self-learning.”

Qiu said that if she could choose again, she would go to another country with better education quality. Like her, many Chinese families with a desire to study abroad are reconsidering the value of studying in the UK.