Black cancer patients feel disconnected from mainstream support because of the lack of representation. How can the space become more inclusive?

When Nevo Burell attended a Macmillan support group meet to help deal with the aftermath of her cancer diagnosis and treatment, she noticed something strange. She was the only black person in the gathering.

“I thought this can’t be right. I know a lot of black people get cancer. Why were they not here?” says Nevo, who is of Nigerian origin.

When Nevo raised this issue in the group, she was told that the black community is hard to reach. “At that point, I thought it was such a strange thing to say. What did they mean by hard to reach?” she says.

Over the next few months, Nevo started making efforts to garner more participation from the black community in these groups. This was when she began to understand the challenges and barriers that prevent the community from reaching out for support from large cancer charities.

She found that many people from the community view cancer from a religious lens and see it as something that is ‘Not of God’. Most people felt that the disease should not be discussed and should be kept a secret.

She also noticed that a lot of people in the community believed cancer to be a white person’s disease. According to Nevo, this perception of cancer was reinforced by the fact that mainstream support organisations appear to have predominantly white participation.

“If all your campaigns have only white people, it it will naturally be perceived as if only white people get cancer,” says Nevo.

An NHS report on the experiences of cancer patients from ethnic minority backgrounds stated that patients from these communities found it difficult to find culturally appropriate support. The participants expressed the need to meet people from similar ethnic backgrounds and wanted an environment that would feel inclusive and welcoming.

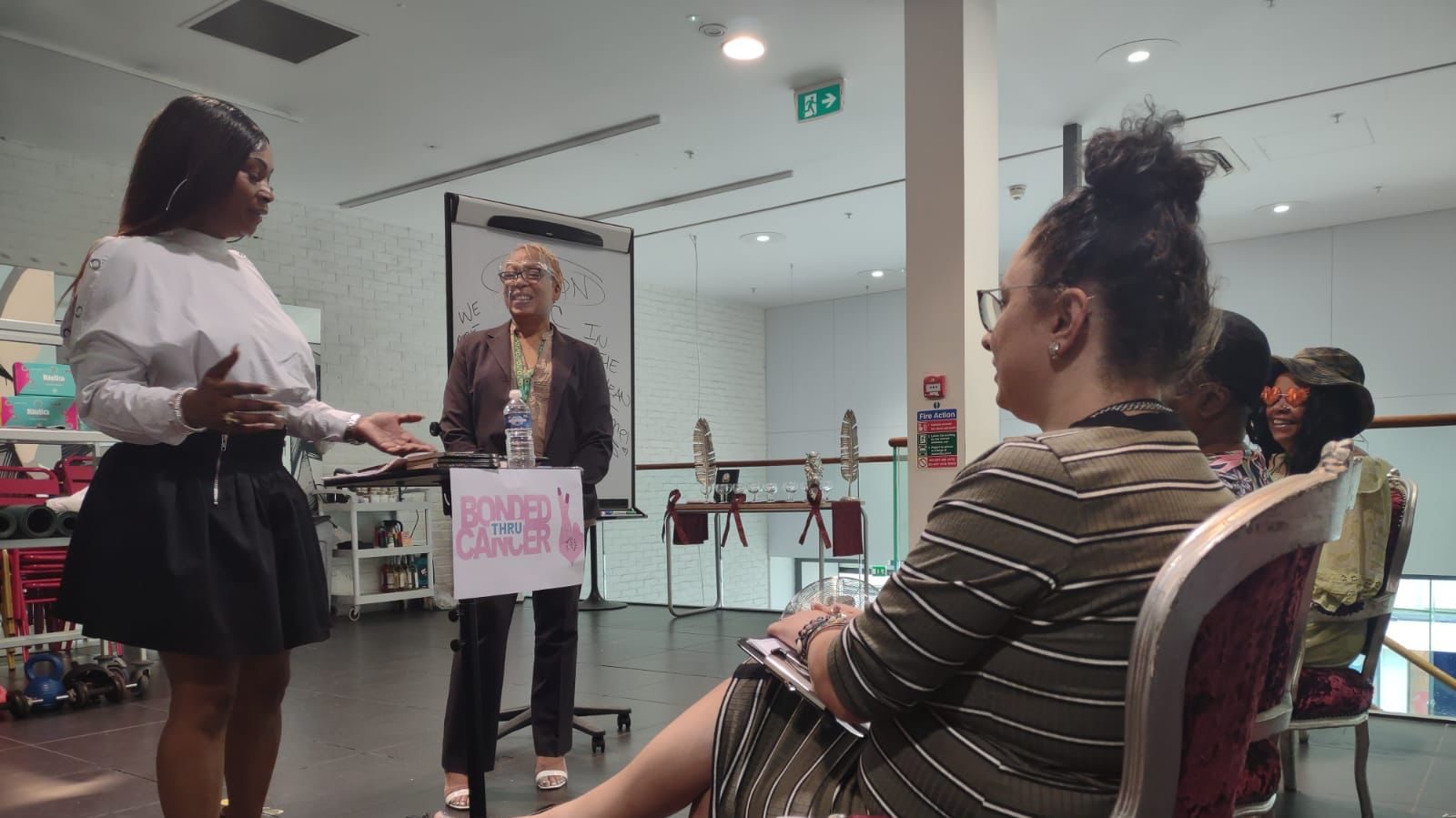

Natasha Veeraswamy of ‘Bonded thru Cancer’ raises this concern as well. Natasha’s charity supports cancer patients across minority ethnic communities and also works with other cancer support organisations like Macmillan, but she says that the presence of the black community in these charities is next to negligible.

“They are not coming through the doors, they are not there at the events, they are not filling out surveys. And that’s because there is nothing to relate to.”

According to Natasha, who is a cancer survivor of African-Indian descent, there is not enough awareness in mainstream support networks, about cultural sensibilities concerning the ethnic communities. There is also a lack of signposting from these organisations to guide people to the right services.

“Even when I was a patient back in 2014, I had no idea what a Macmillan nurse was and how to access the service. I asked other people from the community and no one knew anything about this.”

Macmillan nurses are specially trained nurses with experience and qualifications in cancer care, who can help patients understand their diagnosis, explain to them their treatment options, and support them throughout the treatment. They may work at hospitals, hospices, or in different communities.

Natasha says that even during treatment, patients are often left clueless about what is to follow after their diagnosis and don’t receive support from the doctors beyond physical treatment. A report by Macmillan on BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) cancer patients quoted black patients saying that felt that they were treated like a number rather than an individual.

“For the community, there is a lack of support of where to go, what to do,” says Natasha. “There is medical support in terms of treatment but there is a definite lack of emotional support and understanding for the community.”

Natalie Jones, a cancer survivor from Wales says that while her experience of treatment was mostly positive, there was an oversight during her radiotherapy where the medical team did not clearly inform her about how radiation could affect her skin as a black woman.

“I was burned very badly by the radiation and it was quite distressing. As a black woman I wish they had prepared me better,” she says.

Natalie says that this oversight happened possibly because her radiography team had no person of colour who could empathize with her or understand the issues she could face. “There was ignorance and a lack of understanding. I wish I had more support there.”

But she feels grateful for the support of the Jamaican community from her mother’s side who stood by her throughout treatment and made sure she never felt alone.

“I think Jamaicans love talking about illnesses,” says Natalie as she laughs. “Because so many of us work in the NHS as nurses and carers, they are keen to make sure that everyone from the community is being treated properly.”

Natalie considers community support to be extremely important in helping patients and survivors gain back a sense of normalcy. “Just to have someone to talk to and know that someone cares makes a big difference,” she says.

Laura Omonze, from Nigeria, runs an organization called Cancer Care Diaspora which is based in Manchester. Her organisation is focused on meeting the needs of cancer patients and their families from ethnic minority communities and raising awareness among these people about cancer to encourage timely diagnosis and minimise mortality.

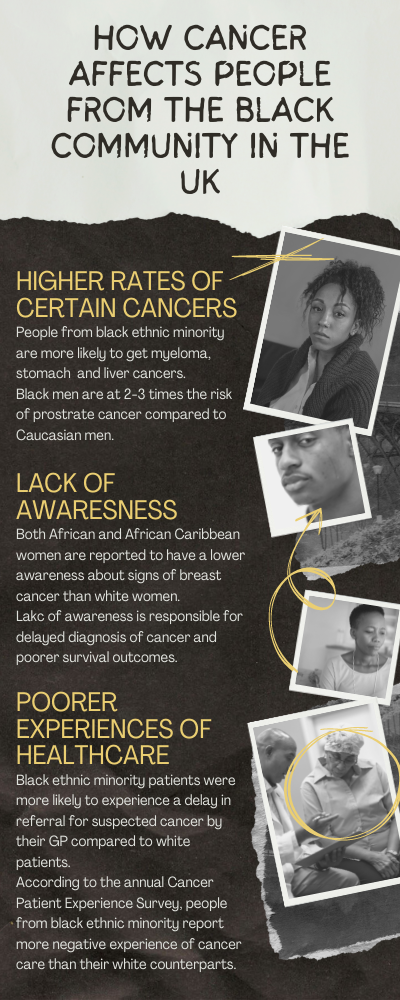

According to Laura, the black community is in urgent need of support but financial and cultural barriers prevent them from getting access to help. Recent reports have suggested that cancer awareness is among the lowest in the black community in the UK and they tend to have a delayed diagnosis compared to their white counterparts. Apart from cultural beliefs and lack of awareness, poverty and marginalization make it difficult for them to consider health as a priority.

“People in the black community tend to sideline their health because they have no time to see the doctor,” says Laura. “They are often in low-paying jobs and cannot afford to miss even a day’s work.”

Laura’s charity regularly holds awareness events to encourage people from the community to attend screenings and not ignore their health. She also provides financial and need-basedassistance to cancer patients.

The organisation arranges culturally appropriate food and other essential supplies for the families where the earning members have been diagnosed and are not able to work because of the illness. They accompany the patients to the hospital for treatment and schedule home visits to make sure that they have everything they require. The charity also provides private tutoring and online classes to children whose parents have been affected.

“People from these communities need this support. So often they have no one to look after them and their needs,” says Laura. “Many of them are migrants. They have big families back home but here they are all by themselves. Sometimes they just need someone to talk to.”

But this support is not easy to provide for a small charity. While the institution does get funding from larger organisations, it is often not enough to support the large number of patients and families that Laura wants to help.

“We don’t have the resources and we don’t have staff because we can’t pay them. If you get volunteers, they are all in full-time paid jobs so they don’t have the time to be available on call. We need more people,” says Laura.

While smaller community-based groups are trying to step up to close the gap in supporting black cancer patients, they struggle with issues like funding and staff shortages. The larger mainstream charities on the other hand have enough resources to provide the necessary assistance to these communities, yet these services only see limited participation from the black and ethnic minority. While they can take the load off the back of the smaller organisations, people are unwilling to reach out to them.

According to Laura a major reason for this is the lack of representation. “Sometimes when we are overwhelmed to capacity, we ask some people to reach out to the larger organisations like Macmillan or Maggie’s but they always refuse. They say there is no one like them in these groups.”

“They always tell me, ‘It’s not our place. No one will see us there,’” says Laura.

Natasha also recounts feeling alienated about often being the sole representative of her community in the cancer support events or groups that she attended. “If you are saying that you are advertising and promoting participation from the BAME community, then why are they not here? Where is this information being promoted?” she asks.

In 2016, research by the British Journal of Cancer stressed the urgent need for targeted campaigns about cancer in ethnic minority communities after finding low levels of awareness about symptoms related to the disease.

According to Nevo, for these campaigns to work, the service providers need to be culturally sensitive and address their unconscious bias. While working with one of the organisations on their campaign, she came across a poster that had a young, smiling, healthy-looking white woman, and next to her was an old black woman who looked sick and unhappy.

“She looked like she was giving up,” says Nevo. “I told them this will not encourage anyone to come and speak because it will strike fear in the people who have been diagnosed.”

She also stresses on the need for these organisations to be visible to the people they want to reach out to. “They need to go to the communities and churches, at the GPs, and put information there for the people to see.”

But Nevo believes representation is a two-way street. While mainstream organisations need to strive to get more participation from the community and increase outreach, the community also needs to understand that for being represented, their stories need to be shared. “There needs to be support for the community but for this support to work, people need to be willing to be seen,” she says.

“You can’t have representation in the mainstream if you are unwilling to stand up and be counted.”

For Natasha, cooperation between various stakeholders for increasing community engagement is the way forward. She feels that if larger charities capacity build with smaller community-based organisations, then these groups can serve as a connecting link between these people and the mainstream.

“They need to build new partnerships with organisations that understand what the black, Asian and minority groups really need,” she says.