With a revolution in cycling technologies underway to replace cars, how are cyclists and active travel campaigners advocating for these new rides’ place in modern transport?

It wasn’t until Covid that Sarah Berry started cycling regularly, spurred by the low-traffic neighbourhoods in Railton, a flat area in south London where she used to live until 2020. But when she moved to Tulse Hill last year, what used to be a quick 10-minute trip started feeling like a treacherous task.

“Sometimes you want your commute to be a workout and that’s nice. You can combine exercise and travel,” she says. “But sometimes you just want to get where you’re going and not be sweating.”

That was until she had the chance of trying out e-bikes. “It’s been a game-changer. It felt like what I used to imagine cycling would be in my childhood,” she says. “It was like flying, as if I had incredible strength. A 10-15 mile trip would’ve earlier left me tired, now I won’t bat an eyelid with an e-bike, it’s a breeze.”

Pedalling up steep hills is far from the list of enjoyable things for a cyclist, but living in a hilly region, as Sarah discovered, turned out to be even more of a challenge. It all changed with the arrival of Meredith (the name she chose for her electric bike), making her a part of the 50,000 other people who bought an e-bike last year. In fact, marketing intelligence agency Mintel found that one in every seven regular cyclists now owns an e-bike.

An e-bike, or an electric bike is not much dissimilar to a regular cycle. The rider still has to pedal to get going, but with battery and motor assistance, lesser effort is required. Sarah says that while that’s obviously a help to her and her peers, it can prove to be even more of a difference-maker for others.

“You don’t have to be physically strong or have really good knees to ride a bike,” says Sarah. “I have a family member who has fibromyalgia, which means that they get really bad pain in their joints. But they have an e-bike and they can get around really well.”

Dr Adrian Davis, an expert in transport and health from UWE Bristol, says that e-bikes are absolutely essential in the transport revolution, especially for older people. He says, “As people get older, they believe that they’re not fit enough to cycle. Well, e-bikes are much less of a toll on your body. Elevation changes are also not a problem as they flatten out hills, so you can go wherever you want.”

People still aren’t as familiar with how easily they could replace driving for short trips.

Sarah Berry, cycling campaigner

Although so far, most of the early adopters of this new technology have been under-45, research from Mintel shows that future purchase intentions are strongest amongst older groups. A senior analyst at the company said that among those who are looking for a new cycle, three out of every 10 people aged over-55 wanted an e-bike.

This could be an outcome of an ageing population becoming aware of the importance of physical activity and constantly seeking ways to stay fit, according to Dr Davis. “From being on the plains of Africa to coming where we are now, homo sapiens need to stay physically active. That is just the way our DNA is structured,” he says.

Dr Davis says that people who are least active are at the most risk of dying prematurely, and cycling regularly is a great incidental dose of the prescribed weekly 150 minutes of MVPA, or moderate-to-vigorous-physical activity.

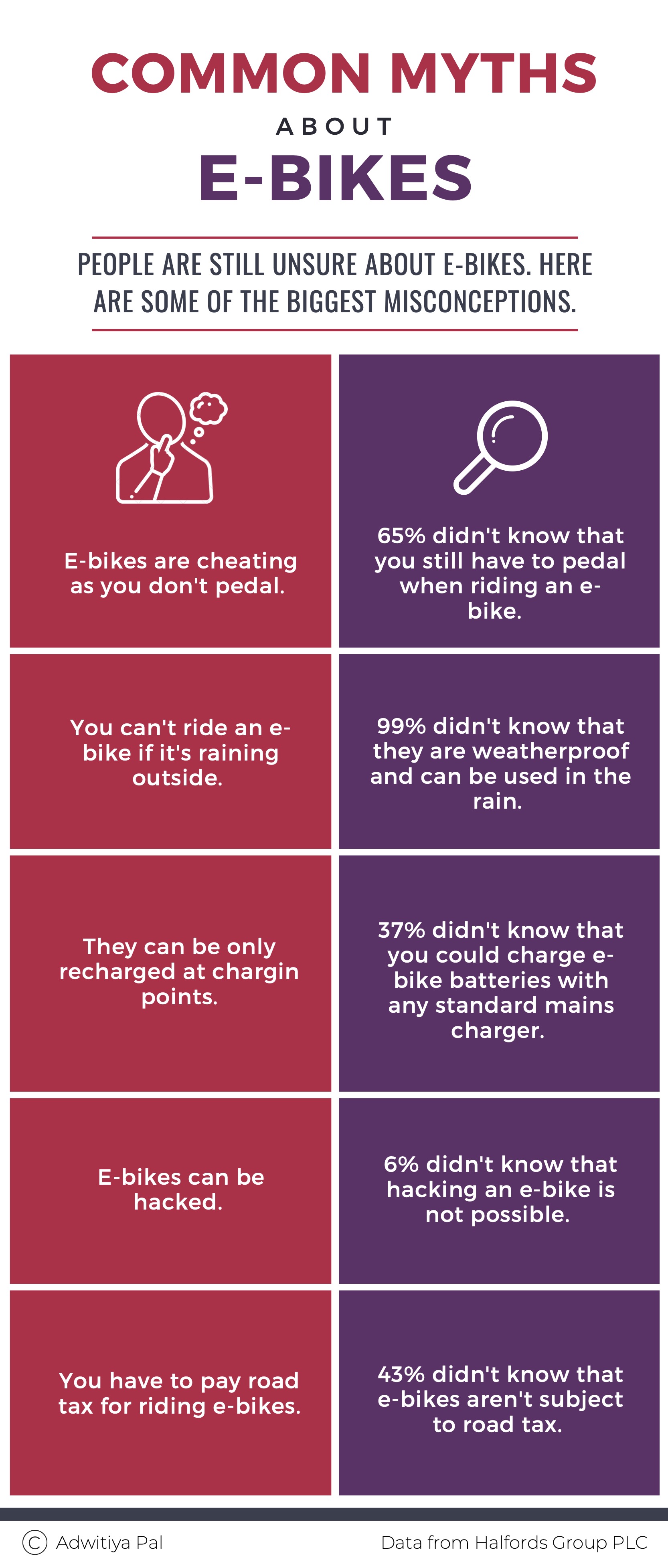

However, a lot of people doubt the health benefits of e-bikes, says Dr Davis. A study from the UK’s biggest cycle retailer Halfords found that 65% people did not know that you have to pedal e-bikes. One columnist wrote in Outsider, “By doing the hard work for you, e-bikes cheat people out of that accomplishment and ultimately make them lazier. They enable entitlement to motion and a sense of false accomplishment.”

Cyclist and journalist Peter Walker says that while cyclists worrying about the lack of physical activity is valid, the concern can be quite easily put to bed. “The battery [in e-bikes] can take up some of the strain, but it doesn’t mean that they pedal themselves. The good news is that people are still participating in physical activity,” he says.

Research has shown that although riding an e-bike burns around 22% fewer calories than riding a non-powered bike, e-bikers tend to travel for longer durations and distances, putting the net physical output on par with regular cyclists,. “It cancels out because by going longer, they are exerting themselves the same as those on non-e-bikes. From my experience, they end up cycling so much more,” says Peter.

While e-bikes offer an alternative commute for most cyclists, they can’t be the direct switch for a lot of drivers, says Peter. However, he believes that cargo bikes, especially those equipped with batteries, are another solution that can take up a lot of the strain from cars on urban roads.

Cargo bikes are usually three-wheeled cycles with a large carriage in front, which can be used for activities ranging from carrying supermarket groceries to dropping children at school. Peter says that cargo bikes are not only incredibly practical for short trips to the markets or deliveries, but his own experience with them has also been quite fun. “The first time I drove my children around in it, they kept insisting on more rounds. This hadn’t happened with a car before,” he says.

But these innovations don’t come without challenges. The most glaring one is the cost. While electrification is aiding the cycling community and making it more convenient and accessible for all, it also comes at a hefty price. E-bikes typically start at around £1000, and e-cargo bikes can cost up to £4000.

But Peter thinks that people need to start looking at them as replacement for cars, instead of an upgrade on bikes. “I’m not saying everyone should ditch their Renaults and Peugeots,” he says. “But small families looking to buy a car should at least consider the thousands of pounds they can save by getting an e-bike or a cargo bike, not to mention all the other benefits cycling provides.”

When shifting her house from one side of Brockwell Park to another in Lambeth, Sarah Berry got the opportunity to witness cargo bikes replacing not just cars but also vans and lorries. “We were able to move beds and sofas just by cycling our way through the park rather than driving all around it,” she says. “The amount of stuff you can transport using these devices can really surprise some people.”

However, Sarah says storage is another problem that has put people off from getting cargo bikes, including her. She says, “They present a really convenient and probably quicker solution than being stuck in traffic, but where do you store it unless you’ve got a garage, which you probably don’t in a city. You can’t just park it in a parking spot.”

Sarah says that to make the switch from cars to bikes as natural and feasible as possible, there needs to be an improvement in the bike shed systems across the whole country. “Hangars or other storage areas need to be normalised both in public spaces as well as flats and houses,” she says.

For now, a number of bike sharing schemes have emerged to help tackle this. One such service that launched in Hackney, London in September last year logged up 500 miles driven in just four months. In February, the Department for Transport offered a £1.2 million fund to 14 local authorities in the country as part of its eCargo Bike Grant to build more sharing schemes and encourage businesses to use them for deliveries.

Sarah, now living in Bristol, has to come to appreciate the assistance of electric bikes even more. “It’s way hillier than anywhere in London,” she says. But that’s not deterring people in the city from trying out new technological innovations to navigate their way around.

Although car is still the primary mode of transport, the increase both in usage and interest in alternative modes in Bristol is something to be proud of, says Sarah. She says that people are becoming aware of the benefits of switching to active travel, with some even attaching trailers to their bikes to come up with a makeshift cargo bike. “I’m blown away with what I’m seeing. It’s really exciting,” she says.

The final barrier that remains to be taken down, according to Sarah is the idea that people are supposed to get into a car even for making the shortest trips. “It’s because people still aren’t as familiar with how easily they could replace driving for those sorts of journeys,” she says.

Sarah thinks that there’s a sea change coming, and that campaigners need to challenge the status quo in the public sphere so people are not afraid to consider giving up cars. “You often find a lot of people saying not everyone can ride a bike or you can’t ride a bike everywhere, but to that I say not everyone can drive a car or that you can’t take a car everywhere,” she says. “It’s not a valid argument, and not good enough to keep people in cars.”