Many LGBTQ+ asylum seekers struggle with trauma and isolation during the asylum-seeking process. How are queer people seeking sanctuary in Britain getting the help that they need?

Mark paces around after he has set the pot of tea and arranged the cushioned chairs to face the television. It’s the fourth Saturday of the month, which means his mentees are expected to arrive at the little room in the church at noon, and for the day, Mark has decided to screen The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, the iconic drag musical of the 90s.

He doesn’t know how many will show up today; sometimes it’s 20 people, sometimes five and on occasion, just one. The uncertainty of their arrival does not faze him. He knows that at least someone will turn up.

In no less than an hour, the room is filled with people chattering about, with the DVD player set up to screen the movie. But for Azi*, these meetups are more than just Saturday afternoon movie sessions.

As a queer refugee from Nigeria who spends most of his time at Cardiff’s City Reformed United Church where Hoops and Loops is situated, Azi says, “Maybe to others it could be an organisation but to me personally, it’s more like a family.”

When Mark Lewis took over the support group that was founded in 2014 to help LGBTQ+ people seeking asylum, there were only eight members at the time. The organisation has grown since, and Mark has helped over 90 people through the tedious asylum-seeking process that they must go through.

“Since I’ve taken over, the group has been evolving. Hoops and Loops is supporting LGBT asylum seekers and refugees who’ve been persecuted and tortured in their country of origin. Now, we are providing a safe space for them to come and we’re supporting them through their mental health problems,” says Mark Lewis.

Although the support group gathers once a month to discuss their ongoing asylum claims and partake in activities to interact with one another, they offer daily drop-in sessions for LGBTQ+ asylum seekers who are struggling with their mental health, one of the prime challenges faced by people seeking asylum on the grounds of their sexual and gender identity.

Salim*, a gay asylum seeker who fled Afghanistan upon being persecuted by the authorities for his sexual identity, expresses that if it weren’t for Hoops and Loops, he wouldn’t have been able to socially interact with people, and talk openly about his mental health. “I can’t explain it, but this has really helped me, and I see them as my family. Everyone is really nice, and it’s helped me a lot with my anxiety,” says Salim.

When there are moments where his post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is triggered, he finds solace in Hoops and Loops.

However, according to a report, despite the mental health needs of asylum seekers being complex, many have difficulty accessing healthcare and support groups in the UK. And queer asylum seekers do not have it any easier.

There is a lack of signposting towards support groups for LGBTQ+ asylum seekers and refugees from the Home Office, according to Numair Masud, a gay refugee and activist. Numair, who campaigns for more mental health services for queer people seeking asylum, also thinks that the government should provide training for them in order to be well-integrated in British society.

Ahmed* is one of many queer asylum seekers who did not get adequate mental health care when he first arrived in the UK. He says that although Plymouth, where he was sent to claim asylum, did have support groups, he was unable to express himself as there was a lack of engagement. But when he moved to Cardiff, he joined Hoops and Loops, which he believes helped him regain his confidence that he had lost when living in Guinea as a closeted gay man, fearing discrimination from his family and society for expressing his sexual identity.

Struggling with PTSD and anxiety, Ahmed believes that the daily drop-in sessions have helped him open up more. He says, “Mark is like a father to me. The way he talks to me, the way he encourages me; he tells me to forget about the past and think positively about the future. He’s done a lot for me.”

Many of those who come to the support group wrestle with PTSD. Mark, who tries to support them until they get medical help, says, “There is a two-year waiting list to see a trauma specialist. So, we have to look at what we can do as a group to manage the individuals through this period of time.”

Having grown up in Nigeria where he faced homophobia from the community, Azi was unable to access healthcare in detention for his mental wellbeing. Battling trauma in the UK, Hoops and Loops is where he found an LGBTQ+ community where he can express himself without fearing being discriminated against.

As he spends most of his time at the support group, Azi says that Mark’s approach of not forcing anyone to open up at group sessions while organising meetups every day, has helped him feel supported without the pressure of having to talk about what he is going through. “When you’re ready to speak you speak. That’s what family is meant to be,” says Azi.

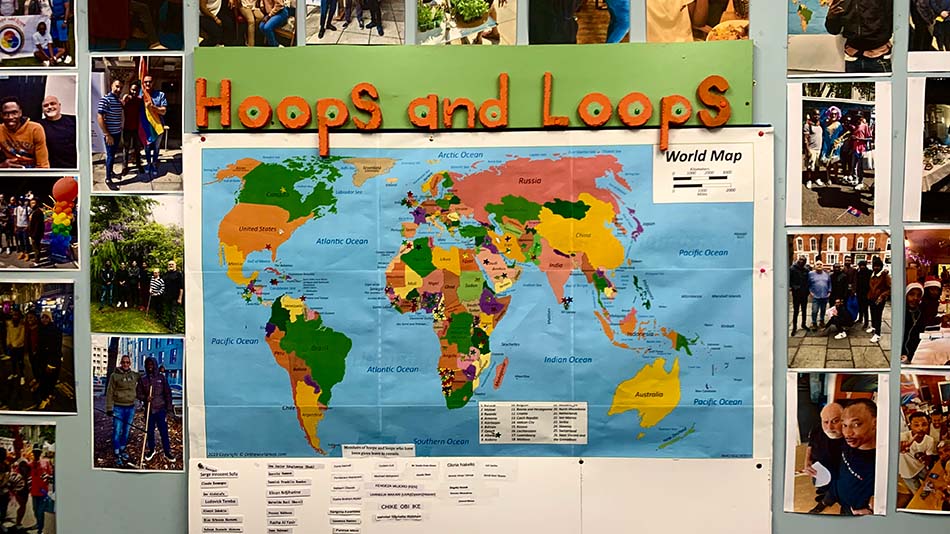

The organisation has members from across the globe which Mark expresses is a melting pot of cultures and identities. “It doesn’t matter where you’re from… Afghanistan, Uganda, Nigeria, Guinea. We’re all one people. There are no boundaries,” says Mark. “As long as they respect each other and are able to spend time with each other, it is important to have that experience which they wouldn’t have possibly in any other organisation in Cardiff.”

The tight-knit community stays connected through their WhatsApp group. Mark encourages them to socialise with each other online, and the idea is for them to talk about their day and develop bonds with each other. “Just for them to say hello or good morning gives them that sense of belonging and that they’re not alone even though they are alone,” he says.

Nevertheless, queer asylum seekers still find it hard to seek mental health support in the country. Moreover, they find it challenging to receive legal assistance during their asylum process.

The cutbacks in legal aid have made it more difficult for queer asylum seekers to get the necessary guidance to claim asylum. In a report by Refugee Action, the number of legal aid providers dropped by 64%. Additionally, queer asylum seekers who require solicitors who provide advice that is tailored for LGBTQ+ claims often do not get the guidance that they need because of a lack of understanding of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) claims.

Circumstances have been made worse as the Home Office demands proof of their SOGI claims, which many struggle to provide as they had to leave their home countries overnight to escape harassment and couldn’t have gathered evidence as they had to conceal their identities their whole lives.

Many are forced to provide proof and back their claims without legal guidance as it quite hard to get legal aid in the country, according to Khakan Qureshi, former Stonewall LGBT Diversity Role Model.

As the decrease in not-for-profit legal counsel providers is concerning, Say It Loud Club, a London-based support group works with legal teams for LGBTQ+ asylum claims. The organisation, which is run by Aloysius Ssali, a queer refugee who campaigns for more support services for queer refugees, says that many solicitors are not well-versed with SOGI claims. This has led to LGBTQ+ asylum seekers having to represent themselves without much knowledge of the system, making it harder for them to successfully claim asylum.

“They rely on legal aid. But legal aid has been cut. A number of firms have stopped receiving people on legal aid. So, all these kinds of policies, they come back to impact those who are already vulnerable,” he says.

Aloysius recalls that back when he was claiming sanctuary in 2010, due to poor signposting, he couldn’t find support as a queer asylum seeker who was also coping with the trauma of having been detained and tortured in Uganda.

“When I was in asylum, I struggled really badly because there wasn’t any source of information for an asylum seeker on the grounds of LGBT identity and that was one of the challenges I faced. So, shortly after I was granted asylum, I wanted to do something about this,” says Aloysius who founded the support group soon after he was granted refuge in the UK, to bridge the communication between queer asylum seekers and solicitors.

In addition to being unable to obtain legal aid, LGBTQ+ individuals also face socio-economic challenges while in asylum. Forced to survive on £40 a week, only a few queer people seeking sanctuary in Britain manage to obtain financial support from charities. Glitter Cymru, which is the only other organisation in Cardiff that supports LGBTQ+ migrants, provides them with financial aid.

The organisation not only caters to the emotional needs of the members but also takes care of the grocery expenses for LGBTQ+ asylum seekers and covers the cost for private counselling, which would otherwise not be feasible for them to pay for, according to Numair, who is part of the team that leads Glitter Cymru.

“A group like Glitter that is trying to support marginalised individuals who might otherwise be overlooked, is something we should be encouraging. Just being able to provide them with socio-cultural opportunities to be part of the UK is important,” he says. “Doing so, particularly for marginalised individuals who have additional challenges and amplified issues is something that we should always support. It is something that I am always trying to support,” says Numair, who advocates for the visibility of queer people of colour in the country.

Funded by Tesco and other private donors, Glitter also provides a social platform for LGBTQ+ ethnic and marginalised minorities to come together and meet people who have shared experiences.

In a panel discussion during Glitter Pride 2022, Chimdi, a queer asylum seeker stated that the support group encouraged them to partake in volunteer opportunities. “As an asylum seeker, I would say it is the best place to be. You are accepted. There is no form of discrimination,” says Chimdi.

Yet, there is a need for more support services in the UK to ensure the wellbeing of LGBTQ+ asylum seekers, many of whom have trouble integrating in British society because of cultural differences and language barriers.

Mark recalls an instance where a queer refugee who went to work ill only for his sickness to worsen, was unaware that you could avail paid leaves if you produced a sick note. Seemingly trivial things like ‘sick notes’ and ‘universal credit’ may be foreign concepts to some of them, and sometimes, they need help to understand it.

In order to help them integrate, Mark wishes that other LGBTQ+ organisations supporting asylum seekers would come together and form coalitions to provide better services. He says, “It is important for them to have the integration and part of what I try and do is give them that. This is why we have an open-door project; It gives them this opportunity to come and be a part of a safe space and to meet people from other countries.”

(Names of the queer asylum seekers have been changed to protect their privacy.)

Below is a map of organisations across Britain that support LGBTQ+ refugees through their asylum journey.