With volunteer organisations sending more Chinese volunteers overseas every year, what is driving their growth and mission? is it altruism or for profit?

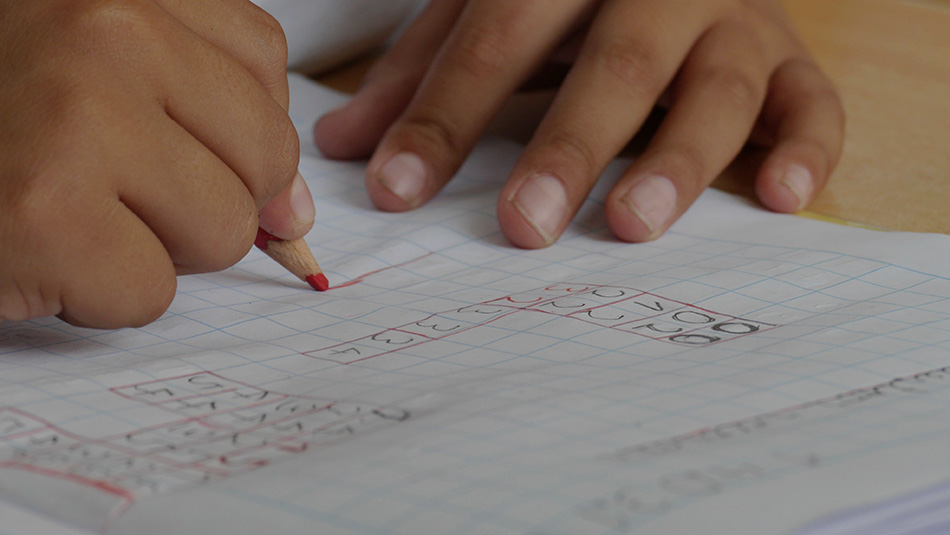

As the bell rang for the end of class at a primary school in Sri Lanka, the children couldn’t wait to run up to the podium and surround the volunteer teacher. With pen and paper in hand, they asked the man to write down his email address so they could contact him, even though most of them had no internet access.

It was the last day for Yuhao to volunteer overseas. During the past month, he has taught the children many things that are not in the textbooks. He believes that the arrival of his volunteer groups not only helps the children to learn more about the outside world but also encourages them to aspire to explore it in the future.

Yuhao decided to participate in volunteer tourism to Sri Lanka for the first time in the spring of his freshman year. And the trip has been a valuable experience for him.

I could see in their eyes a desire for new things and a curiosity about the outside world, which makes me feel that volunteering is something worth doing

Yuhao, now a CEO of a Chinese volunteer organisation

Originating in Western countries, participants of volunteer tourism were usually well-educated young white people. They headed to underdeveloped countries to do something good and help the local communities.

However, as alternative tourism, volunteer tourism has started to gain popularity among young Chinese people during the last decade. According to LeanIn, one of the world’s most famous volunteer organisations, since 2002, more than 92,100 Chinese students have participated in their volunteer tourism, contributing nearly 14,000,000 hours of service in 16 countries.

A search for “volunteer tourism” in Baidu, China’s largest search engine, yielded 21,600,000 results. The first page of results includes the official websites of some well-known Chinese voluntary organisations such as LeanIn, OCVIA, WWB, and Gapper.

These organisations offer volunteer tourism projects at home and abroad for Chinese students. Their projects usually include teaching, animal conservation and environmental protection in remote rural areas in south-western China or underdeveloped Asian countries like Sri Lanka, Nepal and Cambodia. The cost of overseas projects usually ranges from £400 to £500 per week.

Although the industry has seen a boom in China, some experts have begun to question the purpose of these Chinese volunteer organisations. They believe that organisations in China aim to make a profit and neglect the nature of volunteer tourism – altruism. Organisations are usually profit-oriented and make money by selling volunteering experiences to students who want to boost their CVs or experience foreign cultures, according to Xuewei Li, an expert on volunteer tourism in China.

However, Yuhao, now the CEO of one of China’s most famous volunteer organisations WWB, suggests that because Chinese organisations are not supported by the government or any foundations, making a profit is a means to keep these organisations afloat. Being a profit-making enterprise does not mean that they are motivated by making money, according to Yuhao.

“As far as I know, the volunteer organisations in China are currently operating as commercial organisations, which means the organisation needs to have a profitable income to maintain a stable operation,” says Yuhao.

Balancing commerciality and public interest is now one of the biggest problems in China’s volunteer tourism industry, according to Liu Liangbin, the founder of another Chinese volunteer organisation offering projects in Africa. He claims that sectors such as volunteer tourism, which involves a public service nature, operates differently in China than abroad.

“In China, volunteer organisations are questioned whether they are commercial or public interest organisations. There may not be many such concerns in foreign countries, but in China, business and charity, each in its own way,” says Liangbin. “I always think that Chinese volunteer organisations are business enterprises, and we need to survive before we can think about helping others.”

Although volunteer organisations need to make a profit to survive, Yuhao suggests that his organisation was not motivated by making money. During his volunteer teaching activities in Sri Lanka, the children’s thirst for knowledge and the lack of local teaching resources made him feel that volunteering was worthwhile. “The positive feedback I got from the children and their curiosity about the outside world gave me a sense of achievement and brought me great touch,” he says. “That is why I decide to set up my business.”

Besides sending volunteers to underdeveloped countries, Yuhao’s team has also helped some recipient communities improve their education systems in other ways. They delivered “science boxes” to children, giving them access to fascinating natural science and donated equipment such as projectors to enrich local teaching formats.

However, volunteers also have different views on the motivations of Chinese volunteer organisations. According to Wei, who took part in volunteer tourism to Thailand offered by a Chinese volunteer organisation in 2017, the organisations are scamming people with good deeds gimmicks, and profit is what motivated them.

I now look back and think that the so-called overseas volunteer was a bit of a money scam

Wei

She claims that it was more like an ordinary tour with a group as she felt the so-called volunteer teaching did not bring substantial help to the children over here.

The reason for it was that these organisations do not fulfil their duties after receiving money and even issue certificates to volunteers who do not complete their voluntary service, according to Wei.

“They had promised certificates. But it’s funny that they gave us a certificate even though we didn’t finish the teaching task. And I think these projects are something you can get involved in as long as you pay your money, as long as you’re a college student and you’re an adult,” she says. She failed to finish the teaching task because she and her friend had a car accident during the trip.

According to Wei, questions about Chinese voluntary organisations also include the lack of pre-trip training, which leads to some participants being unclear about what they need to do. “We had no pre-trip training, and the organisation had not planned for this volunteer teaching task. They didn’t even tell us what we needed to teach the children,” she says.

Pre-trip training is essential for those who lack teaching experience but want to participate in a teaching project, according to Liangbin. But some organisations do not provide pre-trip training on how to teach while the volunteers are most students and have no teaching experience.

“Most of us were students, and we had no teaching background. So how do we know the teaching methods that local students adapt to? They didn’t tell us any of these details,” says Wei. She believes that neglecting pre-trip training is irresponsible for the volunteers and recipient community.

Liangbin suggests that volunteering requires a certain level of expertise depending on the project’s content. If professional support and training are lacking, volunteering is less effective.

“If a local NGO like the African Wildlife Conservation Foundation wants to recruit a volunteer, they don’t want a novice, and they definitely want someone with some industry experience. So, we need to send volunteers with professionalism in specific fields,” says Liangbin, quoted by Tencent News.

However, some Chinese volunteers cannot meet even the basic requirement of English language skills to participate in overseas projects, according to Ranganath de Silva, an assistant lecturer at Kelaniya University in Sri Lanka. He was responsible for receiving Chinese volunteers from 2015 to 2019.

“Some Chinese volunteers cannot speak English properly, and also sometimes they can’t understand English,” says Silva. “It can be a problem at some time because we cannot communicate well if they don’t understand properly. Because English is important to exchange our ideas.”

According to China International Volunteer Opportunities Research Report 2021, some Chinese voluntary organisations are still unaware of the importance of pre-trip training. The report suggests that some Chinese volunteers provide fewer effective services due to a lack of professional support training.

As a new industry, volunteer tourism is facing a lot of scepticism in China, and there are still many problems that need to be solved, according to Liangbin.

However, for Yuhao, who has participated in volunteer projects and is now running an organisation, volunteer tourism is something worth doing, and he hopes to encourage more young people to join. He believes that volunteer tourism will have a better future in China.

Yuhao is now working to build an online platform to provide volunteers with online volunteering activities. By building networks and donating equipment to local communities, he has enabled Sri Lankan children to continue learning with Chinese volunteers even during the pandemic.

Yuhao believes that these online teaching projects will continue to help the children and provide them with more opportunities. “I hope to bring them a better teaching service and an international environment by interacting with foreign volunteers. Especially for those from difficult families, they have fewer opportunities than those from well-off families,” he says.