As young Chinese graduates struggle to find jobs in a challenging job market, many have had to completely change their plans and abandon their previous dream careers to pursue new path. How do they deal with the gap and rebuild their confidence?

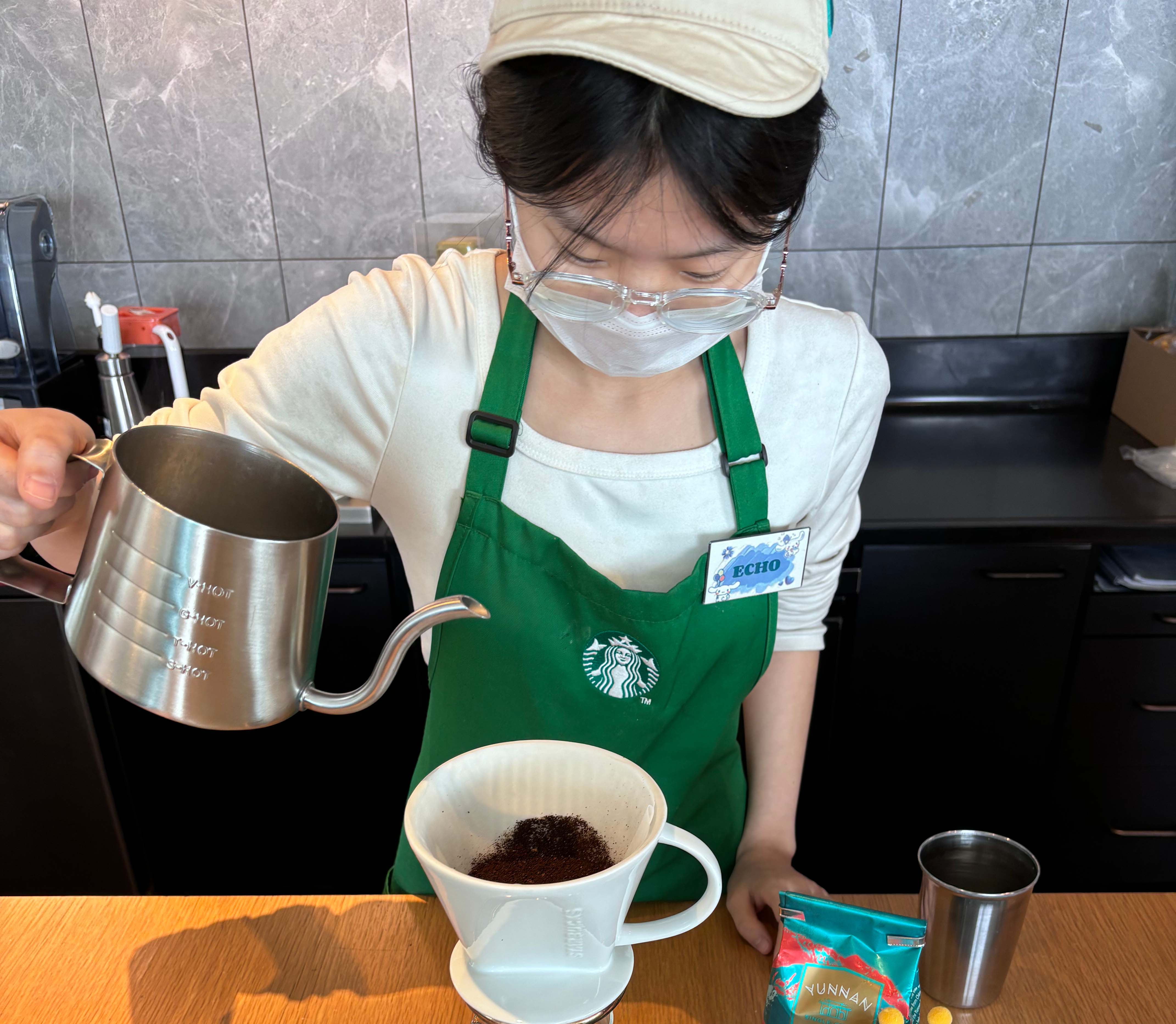

At 6:00 AM, the Starbucks at Yinchuan Hedong Airport was already busy. The smell of baked pastries and boiling coffee filled the air. 22-year-old Xuanxuan, wearing a green apron, stood behind the counter, defrosting the pastries and weighing the ingredients, then preparing a cup of aromatic latte to hand to the customers. Passengers rushed past with heavy suitcases, but she remained focused, greeting each customer with a warm smile.

But a year ago, Xuanxuan was still sitting in her university accounting lecture, buried in ledgers and balance sheets all day. At that time, she thought that after graduation, she would follow the expected path: pass the junior accountant exam, become a certified public accountant, and spend the rest of her life dealing with numbers and financial reports.

“I know some people might think I’m wasting my degree,” Xuanxuan said. “But honestly, many people choose a major in college that they don’t fully understand, simply because others told us those majors were good. It’s only when we start looking for a job that we discover that’s not true.”

Xuanxuan chose this job because the salary was high: “The accounting jobs in our city pay very little. My classmates who are doing internships only earn between 2,000 and 3,000 yuan (Approximately £200-300) a month. By comparison, Starbucks is paying me pretty well.” She works eight hours a day and her salary is around 6,000 yuan (about £600) a month.

Xuanxuan’s story is not unique. In China, many university graduates’ first jobs are unrelated to their field of study. This isn’t because they have abandoned their ambitions, but because the job market has left them with no other choice. According to China’s Ministry of Education, 11.79 million college students graduated in 2024. However, according to a report by Zhilian Recruitment, the employment rate of Chinese college students in 2024 was only 55.5 percent, which means that nearly half of the graduates cannot find jobs.

Even for those graduates who do manage to find work, it remains difficult to realize the career dreams they formed at university, as many are working in jobs that do not match their academic training. According to research from Peking University’s Graduate School of Education, approximately 40% of Chinese university graduates in recent years have worked in jobs that do not match their majors. This mismatch between education and employment reflects a growing disconnect between the promise of a university degree and the reality of China’s evolving job market.

For Xuanxuan, working at Starbucks may not have been part of her original plan, but it also shows that Chinese graduates are looking for instant income in a tight job market, rather than just sticking to the path of finding a job that matches their major. But not all graduates can accept the compromises they have made. It is inevitable that some will feel frustrated and resentful about finding themselves settling for a job that requires little formal education after so many years of hard study.

Young people need options, according to 24-year-old parcel sorter Kun Wan. “I don’t think it’s the students’ reason that we eventually do these jobs. Who doesn’t want a decent job? If we could have other options, we would definitely do. But society hasn’t given us enough jobs to choose from. We feel like mere chess pieces on a chessboard, manipulated by others and powerless in the face of society’s realities,” said Kun Wan.

Kun Wan studied Logistics Management at university, and he had hoped to work in supply chain coordination or business operations after graduation. But after submitting more than 400 job applications before graduation, he was only interviewed by five companies. Four of the companies were actually deceptive “scam companies” and the only legitimate company did not hire him in the end. Finally, he chose to work at a parcel sorting station near his home as a way to cover his expenses.

Kun Wan works every day from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. His daily routine begins with sorting the large sacks of parcels from the distribution center, applying barcode labels to them, and then placing them on the correct shelves. Kun Wan needs to repeatedly squat and stand for hours. Throughout this time, customers constantly come in to collect their parcels, and he helps them as well.

This repetitive manual labor leaves him feeling exhausted. But what wears him down even more is the constant sense of disconnect between his education and his current reality. Kun Wan said: “What I’m doing now has nothing to do with what I studied. It’s simple work, sometimes I think anyone could do it. I didn’t go to school for all those years to carry parcels every day like a machine after graduation. My parents don’t want to see me doing that either.”

As more graduates take on jobs unrelated to their university majors, a new buzzword has emerged on the Chinese Internet: “taking off Kong Yiji’s long shirt”. It represents those Chinese graduates who choose to do low-skilled jobs unrelated to their university majors in order to pay for their living expenses. Kong Yiji is a character in Chinese literature who wore a long shirt and starved to death, because of his stubbornness to only do work related to his specialty.

In March 2023, a Chinese Internet user posted on Weibo (Chinese Twitter), that “Education is not only a knock on the door, but also a high platform that I can’t get off, it is the long shirt that Kong Yiji can’t take off.” This sentence triggered a great deal of empathy among young people. On China’s Instagram, Rednote, the hashtag “Kong Yiji’s long shirt” has received 78 million views and nearly 400,000 discussions.

In the same month, the Chinese official media outlet CCTV published an article on the trending topic, stating: “The reason Kong Yiji fell into hardship was not because he was educated, but because he couldn’t let go of his pride as a scholar and was unwilling to improve his situation through labor.” This implied that university graduates who are still picky about jobs are “unwilling to work.” This statement raised objections among some young people.

The government needs to do more to help young graduates, said Kun Wan, who believes that the statement reported in CCTV is completely wrong. He said: “The government doesn’t explain why the current situation has been caused, they also don’t say how to improve it. They just criticize us, but our efforts in four years of university have been wasted, higher education is like a deception for us.”

It’s time to value all forms of work and rethink how society supports young people entering the workforce, according to Dr. Christian Yao of Victoria University of Wellington. He said: “To help graduates adjust to the sense of failure that their education has been wasted, we need to highlight the value of all types of work, and encourage seeing career change as growth rather than defeat. It is also important to openly discuss the changing job market and the need for adaptability so that young people can build transferable skills and explore new directions with greater confidence.”

Long-term solutions may require wider social change, but many graduates still have to deal with the social gossip that comes with their current jobs now. For some graduates, taking a job that doesn’t require a formal education also means facing misunderstanding and even being laughed at by others. 23-year-old Xiaosu experienced such a humiliating moment.

Selling cocktails at a street stall seems a long way from a degree in Digital Media and Arts, but for Xiaosu, it became a practical choice. After graduation, she worked for a company as a short video editor, but the company unexpectedly closed down after only one month of work. After that, she had trouble finding a suitable job and finally returned to her hometown and started selling self-made cocktails. But she had a conflict with a woman selling noodles because of the stall’s location, who used Xiaosu’s university degree as a point to insult.

“That woman mocked me in front of my customers,” Xiaosu said. “She yelled, ‘Did your parents pay for you to go to college just to let you sell drinks on the street? If you were my child, I would be ashamed of you.’ It wasn’t just the conflict itself that upset me, it was that she believed someone like me didn’t belong there, simply because I had a university education.” Xiaosu still remembers the anger and embarrassment from that moment.

Despite the humiliation, Xiaosu didn’t let it stop her. She changed the location of her stall to avoid seeing that woman again and gradually found strength in doing things on her own way: “I used to be confused about the significance of a degree, but I now feel that a degree is something that gives you a wider range of options. I can choose to set up a stall now, or when I become unable to do this in the future, I can rely on my university degree to find a job again.”

Although Xiaosu has not yet found a clear long-term direction, her words reflect the growing flexibility of some graduates. Experts believe that this mindset change is key for young people to cope with an uncertain job market and career change.

For graduates seeking to rebuild their self-worth after a career change, Dr. Christian Yao offers the advice: “Career changers can focus on the skills they are gaining and the value they bring to their new role, rather than comparing it to their previous academic achievements. Whether through mastering a new craft, helping others, or contributing to a team, finding purpose in their work helps shift their sense of identity.”

This perspective resonates with the experience of Tianjiao. 22-year-old Tianjiao majored in Chinese Language Education at university. However, due to a change in teacher recruitment policies in her region, she was unable to become a middle school Chinese teacher as she had originally hoped upon graduating this year. But instead of falling into frustration, she started trying to do different jobs, even if they were unrelated to her academic background. Now she works as a flower arranger in a florist shop.

Working at the flower shop has not only given Tianjiao income, but also helped her shift her mindset about the academic qualifications. “I have stopped seeing what I can do as so limited,” Tianjiao said. “I used to believe that my academic qualifications would guarantee me something in return. I was once terrified, wondering how I could possibly support myself if I couldn’t become a teacher. But now, what I’ve come to realize is that as long as a person is willing to try, it’s actually not that easy to starve.”

Unlike other graduates who think switching careers means wasting their university time, Tianjiao sees her educational experience in a more positive perspective: “I think I should accept what I’ve learned. Maybe I can’t apply it quickly in my current job, but I don’t feel a strong sense of pain or dissatisfaction. I don’t think my major was useless or my university was bad. I’ve had many joyful moments there. The things our teachers passed on to us during class were a great source of encouragement and spiritual support.”

This shift in mindset is seen as a positive sign of young people’s maturity, according to Dr. Christian Yao. He said: “When young people realize that a degree no longer guarantees a stable or well-paid job, and see a career change as a sign of resilience and growth in adapting to the realities of life, rather than as a setback. It is a sign that they are rebuilding their self-worth.”

This change in mindset came gradually through daily work experience for Xuanxuan, although she initially worked at Starbucks for purely financial reasons. Especially after a customer called the head office to praise her service, she became even more passionate about the job. Xuanxuan said: “When I get the customer’s appreciation, I feel that my work is worthwhile. I don’t really care if I’m successful or not, I think it’s fine to be happy every day and to be able to satisfy your own subsistence.”

Despite feeling upset from being mocked about her university degree, Xiaosu maintains enthusiasm for trying new things: “I’m still young. I’ll try something now and change direction later if needed. Some people love stability, that’s okay. But if you’re someone who loves life, who dares to explore and create, then you should give it a try too.”

Tianjiao hopes that more Chinese graduates will learn to be less anxious about their future path: “Sometimes the pain comes from overthinking and taking too little action. I think many Chinese students easily fall into distress because we’ve been raised in an educational system where we’re expected to simply follow instructions step by step, like little robots completing tasks. But the truth is that the script for what life is really like to live is different for everyone. Our degree is not a ‘Kong Yiji’s long shirt’, but a flexible vest. It’s warm to put on, but not cold to take off.”