As Chinese graduates find it harder than ever to find their ideal job, universities are struggling to provide them with the career advice, social media influencers are trying to fill the gap. Is this really the answer for young people looking for their first job?

Qiyue Ling never thought she would become a career guidance influencer. But after she resigned and shared some insights about job hunting on her social media account, she was flooded with questions from her followers: “How can I get a job at these well-known companies?”, “How should I write my CV?”, and “What should I do if I feel nervous during an interview?”

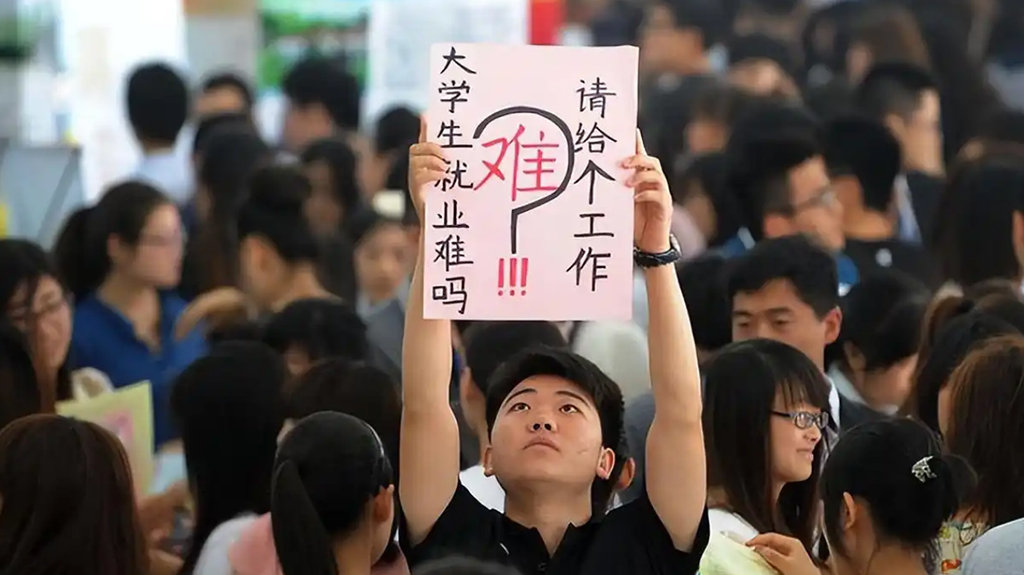

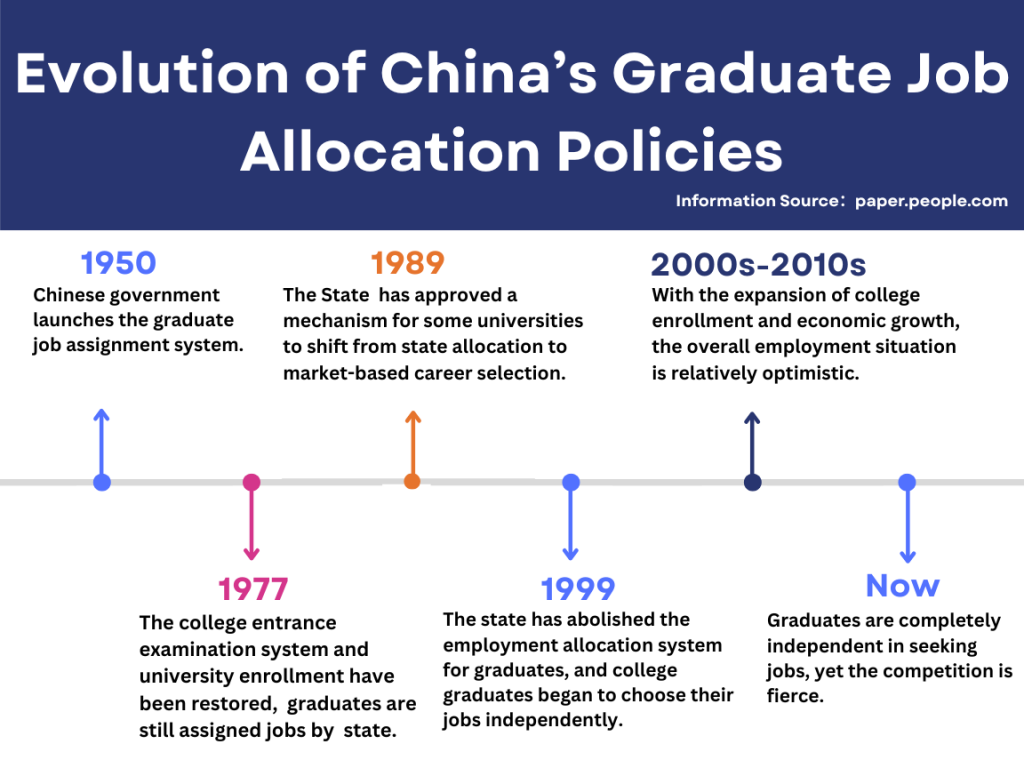

Behind these questions is a wave of anxiety among graduates in China. According to China’s Ministry of Education, 11.79 million college students graduated in 2024. However, according to a report by Zhilian Recruitment, the employment rate of Chinese college students in 2024 was only 55.5 percent, which means that nearly half of the graduates cannot find jobs. Despite earning strong academic records, many of them feel unprepared for the realities of job hunting, because they have difficulty dealing with the current changes in the job market.

What surprised Qiyue most was that some students were still stuck in an outdated mindset about employment. “Some students’ thinking is still stuck in the period of waiting for the government to assign jobs after graduation, I think the university should make students realize the reality as early as possible,” Qiyue said, “A lot of students who can’t find a job, I don’t think they’re not good enough, but they don’t get enough career guidance from universities. What is not taught, how can the students understand?”

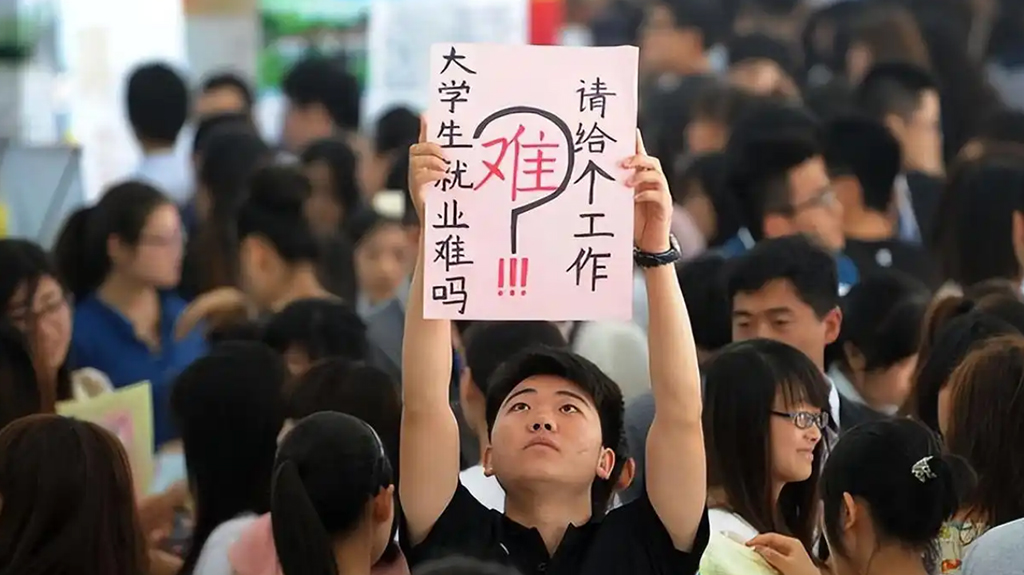

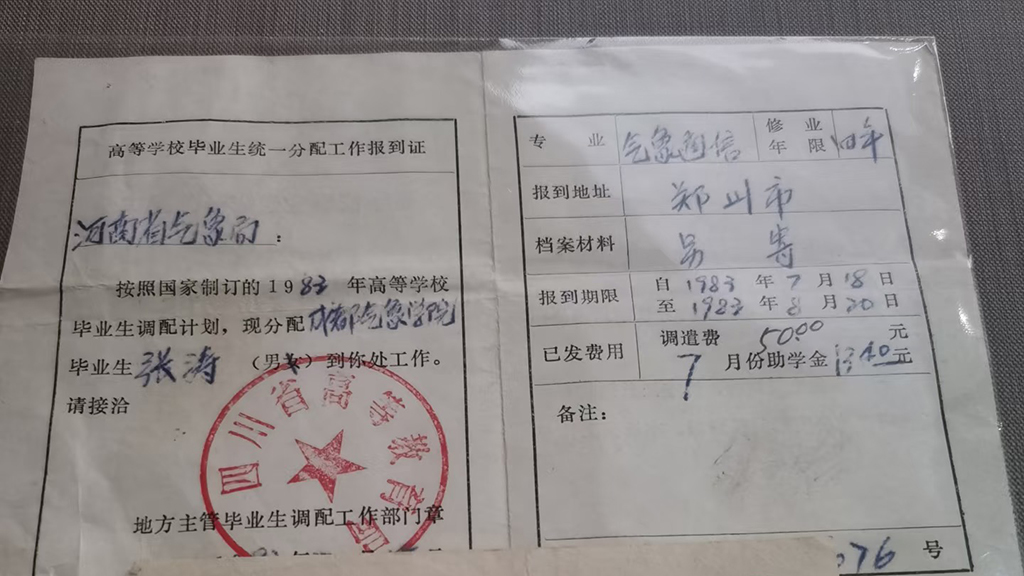

What Qiyue mentioned about the belief of waiting for the government to assign is not just a personal misunderstanding, but a cultural shift that many students and universities have yet to fully adapt to. This disconnect from reality is rooted in a generational shift in China’s job market. Just a few decades ago, the concept of “job hunting” barely existed. From the reinstatement of the National College Entrance Examination (Gaokao) in 1977 until the 1990s, China implemented the principle that “jobs for graduates of higher education institutions should be allocated by the government”. China’s official newspaper People’s Daily once emphasized that “youth should unconditionally obey the state’s assignments.”

This government-led approach meant that graduates moved almost effortlessly from campus to career, which is unimaginable in today’s highly competitive job market. As soon as students graduated, they would receive a formal job assignment notice and often start working within the same month. These jobs were typically in state-owned enterprises, government departments, or public institutions. Employers at the time were required to accept graduates according to the state plan and had no authority to select or hire them independently. This policy supplied China with 12 million specialized talents during its implementation.

Even after China gradually phased out its state-allocated employment policy in 1999, the overall employment environment in the early 21st century remained far less challenging than what today’s graduates are facing. The booming Chinese economy at the beginning of the 21st century has meant that all industries are experiencing rapid growth, and opportunities are still plentiful. For graduates in the 2010s, a higher education degree was often sufficient to secure a stable and respectable job. The concept of “job search” was only gradually being introduced into campus and was seldom perceived as an obstacle.

The employment rate of Chinese graduates remained stable at over 90% between 2010 and 2015, according to the China College Student Employment Report released by the MyCos Institute. But in 2024, that number has plunged to just 55.5%. This proves how difficult it is for graduates to find jobs after China’s economic slowdown. The once large number of elementary jobs has been reduced, and millions of highly qualified graduates are now competing for only a limited number of positions.

This dramatic decline in employment outcomes reveals a deeper issue: a cultural disconnect between what students are taught in universities and the realities of job hunting. As Qiyue explains, many students still expect job opportunities to arrive passively, unaware that today’s labor market demands initiative.

This is related to the Chinese education pattern. For generations, the focus of the Chinese education system has been on academic achievement above all else, and students graduate from universities with no knowledge of job-hunting skills. However, their parents and grandparents cannot offer useful advice because they have experienced in different eras.

Many young graduates are the first in their families to face such a harsh job market. Because their parents grew up during the period of state-assigned jobs, and their advice is often outdated for today’s job market. These helpless parents often want universities to provide help. “My parents are still stuck in the past,” said Liu, a university graduate from Henan. “They think that my inability to find a job is because I didn’t study hard enough, and they also think that the university should arrange every student’s future pathway, the school instructors should be responsible for the students’ inability in finding a job.”

But facing this situation and parents’ expectations, the universities are also not able to provide useful vocational education to these young people. Although China’s Ministry of Education issued a policy in 2008 requiring that universities include career guidance courses in their mandatory curriculum, the actual student experience has been far from satisfactory.

The best place to find those feedback is on Rednote (China’s Instagram). When searching for the keyword “university career guidance course”, the majority of related posts are from students complaining that their teachers just read content from PowerPoint slides from start to finish and offer empty slogans like “stay optimistic during your job search.” The course’s textbook materials often focused on the theory and “significance” of vocational education, rarely touch on practical tools like interview training, CV writing, or real-world career path planning.

These online complaints are not isolated cases. This issue was highlighted in a 2021 survey by China Comment, a Chinese government news magazine, which found that many students find career guidance course’s content is often monotonous, outdated, and failing to keep up with the changing job market. The survey also pointed to a key reason behind students’ dissatisfaction: many universities assign career guidance duties to academic staff who lack industry experience or relevant professional backgrounds. These guidance instructors often have limited time and insight to provide meaningful, targeted advice.

The findings of this survey closely align with the observations of education experts. A Henan vocational education researcher, Professor Zhiyou Zhang points out that there is a disconnect between academic teaching and reality in vocational education in higher education. “Many teachers lack firsthand industry experience. Those teaching the career guidance course may even hold multiple other roles and have no specialized training for the subject. So their classroom teaching remains highly theoretical,” Professor Zhiyou Zhang said.

In this context, even high-performing students can struggle after graduation due to the lack of university instructors’ support. 24-year-old Weining Du is one of them. She is proficient in achieving high marks in exams and has a bachelor’s degree in Health Services and Administration and a master’s degree in Social Work. But since last autumn, she has received fewer than five interviews and no offers, despite submitting more than 500 job applications. During her two years of postgraduate studies, she said, she received “virtually zero professional guidance.”

“Because there were too few professors in our major, the university assigned us supervisors from other majors. Therefore, my supervisor had almost no understanding of the Social Work major. My supervisor didn’t even ask about my dissertation, let alone provide any career advice,” Weining said.

Lacking proper guidance on how to adapt to the job market, Weining’s approach to the job search relied more on guesswork than strategy. Before she graduated, she did internships in three industries unrelated to her major, which she thought would make her seem experienced. However, none of these experiences pointed her in the direction of her future and instead became a hindrance in her job search. “The employers thought my CV was disorganized. As I did a lot during my internship but wasn’t skilled at anything,” said Weining.

One of the biggest frustrations she encountered was misjudging employers’ understanding of students’ internship experiences and academic backgrounds. “I thought having two degrees would make me more competitive, but that became the reason I was rejected,” she explains. Because employers questioned her professionalism and consistency, believing that her change of major from undergraduate to graduate studies was due to a lack of a clear career plan.

“I wish lecturers would teach us how to revise our CVs, how to assess and analyze our personal abilities, and some techniques we could use in interviews,” said Weining Du. “I also wish our lecturers would inform us of the various career paths associated with our major at an earlier stage, rather than leaving us to figure it all out by ourselves.”

Weining’s story is not unique. The gap between what universities teach and what employers expect is pushing many young people into blind decision-making. One of the most obvious results is that many graduates are keen to get into “Internet giant” companies, not because they really understand the positions, but because the major media overstates the concept that getting into these companies represents “career success”.

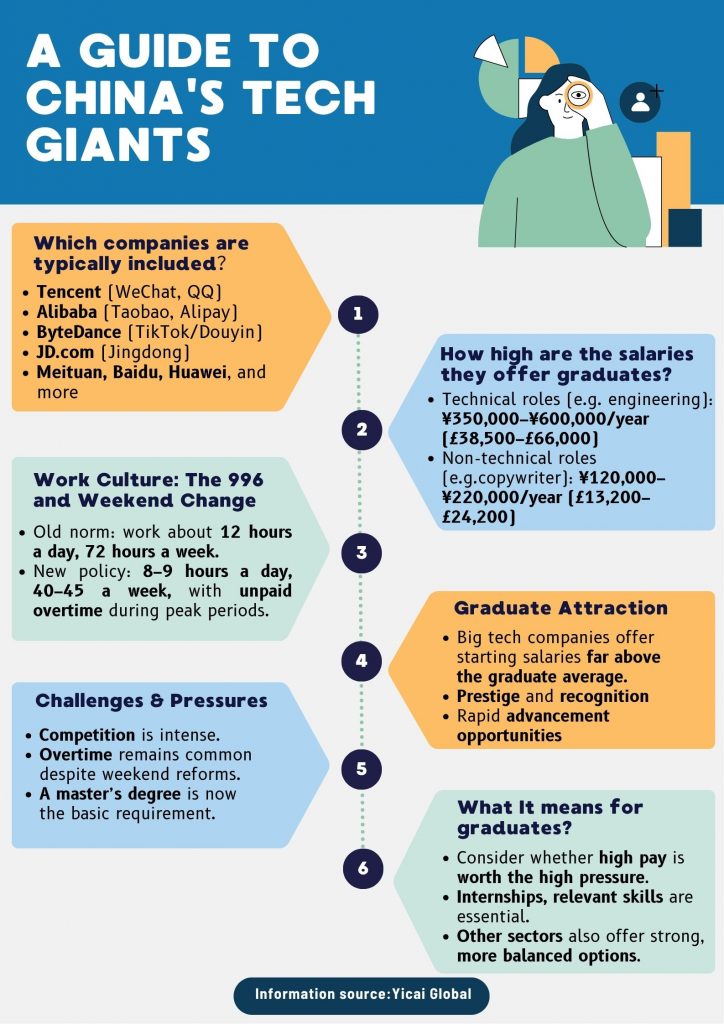

A report by Zhilian Recruitment in 2023 reveals the job search preferences of Chinese graduates: among the many considerations, “salary and benefits” and “social recognition” are the two most important aspects for graduates, with 69.3% and 40.7% of graduates choosing them respectively. In the Chinese job market, these important factors are usually associated with Chinese Internet giant companies such as ByteDance, Crypto, Tencent, Alibaba, and Jingdong. On China’s TikTok, Douyin, the hashtag “Experience of working in the Internet giants” has received nearly 2.7 billion views, which prove that the topic receives a lot of attention.

However, hiring at these companies is highly selective and the competition is intense, with some firms having offer rates as low as 1% to 2%. Facing fierce competition and general confusion about how to get into these companies, and receiving little practical guidance from their universities, many graduates are seeking help from experienced people through social media.

This is how Qiyue Ling, a former ByteDance employee, became a career guidance influencer on Rednote. Unlike some students who don’t have a plan for their future employment while studying in university, she had several internships at Chinese Internet giants while studying at university. After graduation, she worked as an HR at ByteDance, which gave her the firsthand insight into the hiring standards of major Internet companies.

After quitting job to care for her sick mother, Qiyue casually shared some past work experiences online. Initially, she just wanted to help recent graduates who had a passionate desire to work for these companies but lacked a clear strategy. To her surprise, her account quickly became popular and had more than 40,000 followers. These followers left comments on her posts, asking for help with job search strategies. “One follower told me that what I taught was making up for the lack of the university career course,” Qiyue said.

In the process of guiding followers, Qiyue discovered from their stories that the heavy course load and strict school regulations are also key reasons for their lack of experience. “The teachers believe a student’s main priority is to study, so they schedule loads of school classes. Furthermore, many universities fear being held responsible if a student has a safety issue off-campus, so they often don’t permit students to take external internships. But employers often pay great attention to internships.”

Qiyue’s thoughts reflect a broad reality of the job market: academic qualifications alone are no longer enough. With an increasing number of graduates, employers are looking for graduates with both qualifications and employability skills. According to a survey conducted by BOSS Zhipin in 2023, more than 60 percent of Chinese employers ranked “job-related internship experience” as the top criterion for hiring, even higher than GPA or university degree.

Although Qiyue cannot offer students real-world experience like internships, she is doing her best to address the gaps in job-hunting skills through guidance based on her own limited experience. So far, her public posts on Rednote about job-hunting tips for graduates have received over 800,000 total views and guided countless students in their career search. And her one-to-one mock interview tutoring has helped nearly a hundred graduates get offers from their dream Internet giant companies.

In recent years, many career guidance influencers like Qiyue appeared on Chinese social media platforms. While their presence can fill a gap in formal education to a certain extent, they are also limited in their ability to truly prepare students for the world of work. Most of these influencers rely on personal experience rather than professional training, and their content, while well-intentioned, cannot fundamentally solve the problem.

Although because such individual efforts are not a fundamental substitute for the responsibilities that universities should undertake, education experts are also calling on universities to take a systemic approach to assist students’ employment dilemmas. To address this issue, Professor Zhiyou Zhang suggested that universities should transform their teaching methods and strengthen collaboration with corporations to help students lay the foundation for their job search after graduation.

He said: “Universities should offer more practical courses and reduce the proportion of theoretical ones. Moreover, universities often fail to establish deep partnerships with businesses and are unable to provide good internship opportunities for their students. They also need to establish close partnerships with companies to jointly develop talent development plans. They can run joint training projects, allowing students to master real-world work skills through practice.”

In addition, Professor Zhang also suggested that universities actively organize various vocational skill competitions to help students enhance their understanding of and preparation for formal employment. He said: “This allows students to understand the actual working environments and requirements of different professions through hands-on experience, enabling them to choose their career paths more rationally, adapt to market demands, and achieve their own career aspirations.”

While experts are calling for systemic reforms, until these reforms take complete effect, young people will have to keep experimenting in this uncertain environment. For China’s new generation of graduates, the job search is no longer just about submitting a resume, it is a test of their adaptability and flexibility.

Although what Qiyue offers is not a fundamental solution, her story also reflects the fact that some young people are learning to be more active in finding their own way, rather than passively waiting. Qiyue wants that graduates get more from her than just job offers and job-hunting help: “I hope they also gain confidence in themselves and learn to truly approve of themselves from within. The biggest misconception is thinking your academic qualifications determine everything. As long as you’re working hard in the right direction, you absolutely deserve a good job.”

She also advises graduates who lack a clear plan to think carefully before following the crowd: “Not everyone has to work for an Internet giant. The key is whether your own career plan is clear enough. If so, then you should firmly follow the path you want to take instead of blindly following others.”