In China, stable and prestigious jobs are seen as the reward for years of education, but some graduates are now voluntarily quitting after experiencing these ideal jobs. What motivates these young people to abandon “success” and pursue a different kind of life?

As night falls on Changsha, the warm lights cover a corner of the snack market, and sweet scents drift from steaming pots, mixed with the soft whispers of the evening customers. Meili Wen, 31, sings lightly while organizing the tea jelly, fruits, and sweet wines on her trolley, and waits for the next customer to arrive.

Her life wasn’t always at such a cozy pace. Three years ago, Meili was an ordinary white-collar employee in Changsha. She used to carry a laptop bag and a cup of coffee to work. Sometimes, she would get out of a taxi and run towards the office building in high heels to avoid being late. At that time, she struggled to meet the company’s goals, and her daily work made her incredibly tired and exhausted.

“In my final job, I was thinking every minute of the day about how to prove my value and what I had to do to make my boss satisfied,” Meili said. She finally decided to quit when she realized she wasn’t able to celebrate the business she worked for in the way her boss wanted her to. “My boss disliked me for being too rigid, too clumsy, and for not knowing how to read the room. When he made a boastful statement that ‘We are the best advertising company in Changsha’, I couldn’t say anything to support him.”

Meili is typical of lots of young Chinese people. According to the Hudson Global Employment Trends Report 2024, China’s annual employee turnover rate has reached 18.9 per cent, one of the highest in the Asia-Pacific region. Meanwhile, the 2025 China Human Resources Market Monitoring Report shows that among Chinese youth aged 20 to 35, the typical length people stay in their jobs is just under eight months down from almost 22 months seven years ago. This sharp decline reflects a growing trend of job instability and frequent career shifts among young people.

Meili may not be a career person, her current life selling snacks in Changsha might look like a step down, but she is happy with the decision she made. After resigning, Meili began to think seriously about what she wanted: “I decided I wanted to do something for myself.” In the summer of 2023, Her first product was egg waffles to avoid competing with the dominant spicy snacks. But soon she switched to sweet wine, which was produced faster and more popular. A year after leaving the office, Meili found the new direction in her life: “I found a path I hadn’t imagined.”

There are increasing numbers of highly educated young Chinese deciding to abandon stable and even enviable jobs. A Chinese buzzword is “naked resignation”, which means quitting job without finding the next one. On China’s popular Internet forum Douban, a group called “Naked Resignation People’s Small Communication Organization” has more than 210,000 members. On China’s Instagram, Rednote, the hashtag “naked resignation” has received more than 2.5 billion views.

Behind the rise of “naked resignation” is a growing disappointment with the realities of working life. Some were suffering from exhaustion, with overlong working hours leaving them feeling constantly worn out. Others mentioned that their work was too repetitive, disconnected from reality. Some were unable to deal with their colleagues because the workplace they were in was bureaucratic. Even those who were once confident in their careers are gradually losing their sense of purpose. A Douban user said: “Quit my job was the end of the vicious cycle that I can’t stand anymore.”

Beyond dissatisfaction with job content and working environments, mental health issues have also become a key factor driving resignations. A 2023 study by Frontiers in Public Health found that young Chinese employees who work over 60 hours a week are 22% more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety than those with regular hours. The risk is particularly high among workers under 35.

The psychological problems caused by the work pressure endured by these young people have also drawn the attention of medical professionals. “Overwork usually refers to a series of physical and mental health problems that affect work efficiency due to factors such as long working hours, high labor intensity, and great psychological stress.” This situation is more common among workers who work overtime under the “996” schedule,” said Wei Sun, president of the International Society for Medical Shockwave Treatment.

For people who are overwhelmed with mental stress, quitting a job is not only a way to escape a high-pressure workplace, but also a way to protect their health. Not everyone makes a smooth transition to their favorite job, and some young people chose to go back to campus and find a new direction by retraining.

Yun, 27, is a second-year graduate student at a university in northern China. She now has a more urgent reality besides the pressure of her studies: after quitting her journalist job three years ago, she is approaching graduation again and facing the same uncertainty about job search.

In 2020, Yun graduated and worked as a newspaper journalist in Liaoning Province. To many people, this is a respectable job. However, only she knows that her career choice was largely influenced by her classmates and that she never really had a passion for it. After entering the industry, dealing with multiple people on a daily basis as well as revising drafts repeatedly left her feeling exhausted. She soon realized it was not suitable for her.

For Yun it was a combination of stress and lack of pay that made her make the decision to leave. “I aspire to a regular routine more than I do when I was scheduled to go out with my friends on a weekend, but was called back by a leader with a phone call to revise the article,” said Yun. “There are actually many people with a journalistic ambition, but I didn’t have that motivation in the beginning. I was more concerned about whether my hard work matched the rewards.”

Yun still vividly remembers the day she decided to quit her job three years ago. The interviewee she had arranged to meet canceled at the last minute and didn’t show up. She kept negotiating with her supervisor, hoping to delay the publication, as she couldn’t find a suitable replacement interviewee. At that moment she made up her mind to leave the job and go to pursue postgraduate studies. She said: “I must leave, I don’t feel a sense of fulfilment or joy in this job.”

Yun’s experience reflects a deeper contradiction faced by many young people in China: even if they find a desired job that doesn’t seem to be a waste of university knowledge, they may find after a while that the job doesn’t match their personal pursuits.

In China, higher education has long been viewed as the surest path to upward mobility. For decades, students have been taught that studying hard and getting into a university guarantees a stable, respectable job. This perception is particularly strong in lower-income families, where parents often invest their life savings in their children’s education. For Chinese parents, having a child graduates from college and obtains a stable and prestigious job, such as teachers, lawyers, or white-collar in a technology company, is not only a sign of the child’s personal achievement, but also a symbol of the success of the family education.

As a result, many young Chinese people grow up with an entrenched expectation that years of academic effort must be rewarded with social recognition and financial stability through obtaining a stable, decent job.

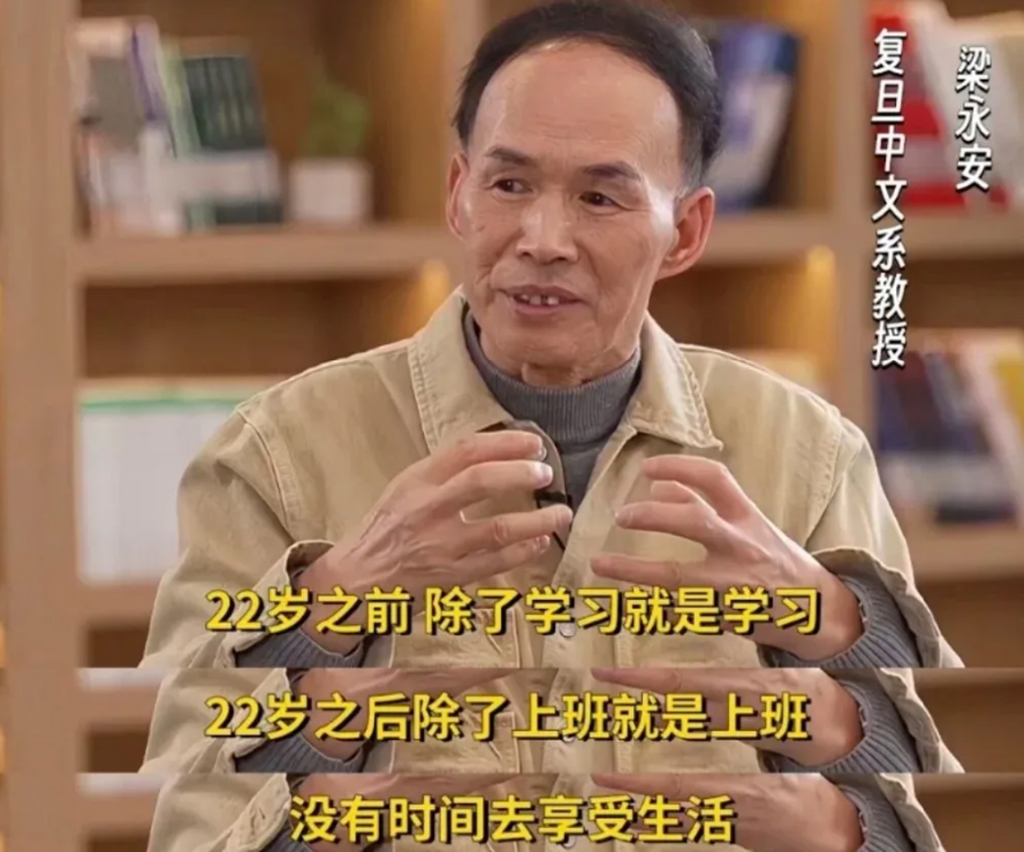

Fudan University professor Yong’an Liang believes this is due to a fundamental difference in worldview between the generations. When speaking to The Paper, he said: “The previous generation is more biased towards the cultural psychology of the farming society, the desire for stability and security, many parents’ expectations of their children remained at obtaining a stable job, buying a house to get married. But the young people are more inclined to the way of thinking of the Age of Sail and are more adventurous.”

So when a young person abandons a decent job that carries all the hopes of their parents, the uncertainty of the future is only part of their difficulty. The bigger challenge often comes from family, with disappointed and confused parents struggling to understand why their child would willingly give up a seemingly stable career to pursue the unknown.

26-year-old Wu Lin has experienced this intergenerational dilemma. After graduating with a degree in Public Administration from a top Chinese university, she obtained what many would consider a perfect first job: working in a disciplinary inspection role at a state-affiliated public institution in Guangdong.

She once had high hopes for the job because she will be able to participate in the development of the country. Her parents were also proud, in Chinese society, working in a government department is something that earns the admiration of friends and relatives.

But the actual job duties quickly smashed Wu Lin’s expectations. Her daily routine involves dealing with disciplinary reports and supervising complaint, was physically and mentally exhausting. The complaint-handling work also requires her to report colleagues’ mistakes to superiors, which put her in conflict with her colleagues and even ostracized by them. As time passed, Wu Lin had psychological problems. “I started to feel anxious and even depressed,” she admits. “I couldn’t sleep all night. I thought I couldn’t do this anymore.”

However, resigning wasn’t as simple as she thought. “The biggest resistance came from my family. In my parents’ eyes, quitting that job was like throwing away everything they had worked for.” Wu Lin said. Her parents couldn’t understand why she’d give up such a prestigious position, and were more worried about losing face. She recalled: “I once joked that I could work at the milk tea shop, and they said, ‘Fine, but you have to do it somewhere far from home.’ They were more concerned with what the neighbors would think than how I felt.”

Even after she moved back home and decided to take the postgraduate entrance exam, her parents couldn’t accept her decision. “I had explained countless times why I resigned, but they questioning me further about it,” Wu Lin said. “They still don’t understand why I left and are unwilling to talk about it with others.”

Being a young woman in China makes this problem even harder, according to Yun. When she resigned and prepared to return to campus, her mother developed new worries. Yun recalled: “My mom said, ‘You’re near 30, and you’re going to study for a three-year master’s degree? How old will you be then before you can get married and have children?’ She even said, ‘A woman’s natural duty is to have children,’ which shocked me.” This disagreement led to a fierce argument, but it only strengthened Yun resolve to finish her postgraduate studies and pursue a new direction in life.

While many parents find it difficult to understand or accept their children’s career changes, the expert believes that parents should offer emotional support rather than control. Professor Yong’an Liang said: “Contemporary Chinese parents should act as a harbor, watching their children leave home and being prepared to welcome them back from any hardships or setbacks they may encounter on their journey, helping them to heal and rest before they set out again.”

He also believes that quitting is not giving up, but a pause for young people to rediscover themselves and the world: “ If young people simply follow the traditional path from graduation to employment, there’s a ‘missing link’ in the process, which is the phase of self-exploration. If they haven’t experienced the world, they won’t be able to understand its vastness and diversity, and will lack competitiveness and growth potential.”

In his view, it’s reasonable for young people to quit unfulfilling jobs and search for a life that truly suits them. “You only need to work half your life. You live in this world, you must try to live the life you love, ” Professor Yong’an Liang said.

This mindset has begun to resonate with many young people, who are no longer content to accept unhappiness as the cost of a “decent” job. While the uncertainty of leaving a job and the pressure from family can be overwhelming, for many young people, resigning becomes their first step to actively moving away from rigid systems and societal expectations.

“Although I haven’t thought about what job I’m going to take after I complete postgraduate studies, I know that if I continue that job as a journalist, that kind of pressure and anxiety would never have disappeared,” Yun said. She now spends her spare time in public service activities and volunteer work. Instead of being obsessed with financial rewards, she has gradually found inner peace in these ordinary contributions. Yun said: “These things won’t bring me success or money, but it makes me feel that my life is more valuable.”

For Meili, running the snack stall didn’t just change career, it transformed her mindset. “I used to be passive at work, only doing what was assigned to me and never really wanting to do it,” she said. “But when I started running my snack stall, I became proactive. It was something I chose, so I wanted to make it better. I started noticing problems, thinking of solutions, and trying to improve.” She described this transition as going from “just waiting to die” to truly engaging with her life.

“To put it simply, I think success is living the life you want. Even if you haven’t fully achieved it, as long as you’re on the way, it’s success,” she said. “If you compromise with yourself and do things against your heart, that’s what makes life feel hard.”