The UK is currently experiencing a wave of anti fast fashion. Are British environmentalists sewing in public spaces boosting awareness of fast fashion?

Suzi sat in the bustling Oxford Street, spreading out a slightly torn yoga pants on her lap. She gently inserted the needle tip into the crack of the leggings, tightened the thin thread, and slightly gathered the fabric, each time accurately threading through the fabric surface, sewing the tear bit by bit.

This behavior attracted the attention of many passersby, including security personnel. Interestingly, she was not driven away; instead, someone came forward and asked her to help mend the hem of her shirt.

The origin of street patching was actually an accident, “Suzi said.” At that time, during the pandemic lockdown, I accidentally heard a podcast that interviewed Orsola de Castro, co-founder of the Fashion Revolution movement. She mentioned that fast fashion clothes are called ‘cheap garbage’ because they are quickly thrown away as disposable items. ”

Suzi Warren is a handicraft artist who advocates for sustainable fashion. She was influenced by Orsola to launch the “Street Sewing” campaign, aiming to raise public awareness of sustainable fashion by sewing old clothes on the streets. Unlike radical protest methods, street patching is more like a gentle initiative, conveying her ideals through quiet yet powerful actions.

This concept is a continuation and interpretation of Orsola de Castro’s advocacy. Orsola de Castro is an international leader in sustainable fashion, pioneering the upcycling concept and actively promoting the “Loved Clothes Last” philosophy. She advocates reducing purchases, extending the lifespan of clothing, and helping the public change their way of wearing through education, media, and social movements. In her opinion, although cheap clothes allow more people to pursue fashion at low prices, they often use inferior materials and fast production processes, which are prone to damage, fading, and deformation, causing a vicious cycle and wasting a lot of resources.

The ultra-fast fashion that originated on TikTok continues the characteristics of fast fashion, such as low prices and fast updates, but at a faster pace and with more frequent updates. It not only inherits the problems of poor quality and easy disposal in fast fashion but also uses social media and algorithms to accurately place advertisements, constantly stimulating people’s impulsive consumption habits of “buy and wear,” making shopping faster and more addictive.

To reduce the impact of fast fashion, citizen movements such as “Say No to Shein” have emerged in the UK. They have joined forces with many British politicians and retail consultants to launch a petition to the government, demanding a thorough investigation of SHEIN’s labor and environmental disputes before its listing.

In addition, the charity organization Fashion Declarations, in collaboration with the law firm Bates Wells, will release a white paper titled The Future of Fashion Regulation in the UK in May 2025. They put forward three major reform proposals: closing tax loopholes for speeding “extremely fast fashion” products, implementing the “Extended Producer Responsibility” (EPR) system, and deploying “Digital Product Passports” to enhance industry transparency, sense of responsibility, and circular economy mechanisms.

Besides policy advocacy, social media also plays an important role. A report titled The Online Movement Against Fast Fashion points out that the emergence of ‘green influencers’ has made platforms an important channel for promoting, protesting, and advocating sustainable fashion. They promote zero waste and sustainable fashion, raise public awareness, encourage slow fashion, oppose fast fashion, and guide people to think before consumption, thereby reducing impulse buying.

Suzi believes that although the poor quality of fast fashion clothing and rapid updates are indeed factors causing waste, what really makes the fashion industry unsustainable is actually the consumer’s own consumption concept. She said, “Many people place their happiness on buying new clothes, thinking that only brand-new and shiny clothes can reflect their value and identity. So I think the key to truly solving this problem is to completely change people’s perception of clothing. Anyway, we have to start with small things. And one way to make an impact is to remind people that wearing the clothes you already have can also be a meaningful and powerful choice.”

To illustrate that “repeated dressing” does not mean giving up fashion and elegance, Suzi cited the example of Kate Middleton: “She often wears formal dresses and eye-catching clothing repeatedly. From the weddings of Prince Harry and Meghan to multiple royal visits, she has worn the same set of dresses repeatedly. Her behavior has made people realize that repeated dressing can also be beautiful.”

Influenced by this example, people are starting to rethink the meaning and value of what they wear. Suzi believes that this shift in mindset is the key to triggering real change. She pointed out that encouraging people to accept repeated dressing and repairing old clothes may quietly spark a small revolution about “fashion thinking.”

Although the UK has not yet enacted relevant laws, people’s consumption behavior and habits are gradually changing. The UK Sustainable Consumer Report states that 55% of adults in the UK have attempted to repair items rather than purchase alternatives in the past year, and 76% have expressed a willingness to try repair services—indicating that repair is gradually becoming an accepted way of consumption.

Behind this trend, it cannot be separated from the promotion of handicraft artists and fashion designers who advocate environmental protection concepts. Represented by Suzi, they have launched a series of public welfare knitting and sewing activities, encouraging people to extend the service life of clothing through repair rather than purchasing it at will. Street Stitching is a very successful example of this, bringing sewing behavior that originally belonged to family spaces into public places, making sewing not only a practical skill but also a way to openly express a sustainable lifestyle attitude.

In the “Street Sewing” event, participants sit on commercial streets where fast fashion brands such as London and Edinburgh gather, publicly repairing old clothes and demonstrating sewing techniques. They actively teach simple repair methods to passersby and encourage everyone to extend the lifespan of their clothes. There is a hand-sewn banner hanging behind each chair, prominently reading #StitchItDontDitchIt. They carry sewing baskets, sew clothes on site, and teach interested pedestrians.

To attract interested members of the public, each repairer carries a QR code linking to a free online tutorial resource library, covering various clothing renovation, patching, refurbishment, decoration, and upgrading tutorials. Practice has proven that this effectively breaks the excuse of “I don’t know how to sew” and allows people to get help without saying much.

As Suzi shared the video of their first event online, more and more people were inspired and joined in. In just a few weeks, people from 50 to 60 towns around the world responded one after another. They sat down on the bustling commercial streets of their respective cities, sewing clothes in public, hoping to arouse the curiosity of passersby and engage them in conversation.

This seemingly simple act of sewing is gradually changing people’s perception of fashion and consumption. It not only encourages people to repair old clothes but also raises awareness of resource waste and environmental responsibility. Suzi and her sewing partners convey a concept through their actions: fashion does not equal novelty; repetition and renovation can also showcase beauty and self-expression.

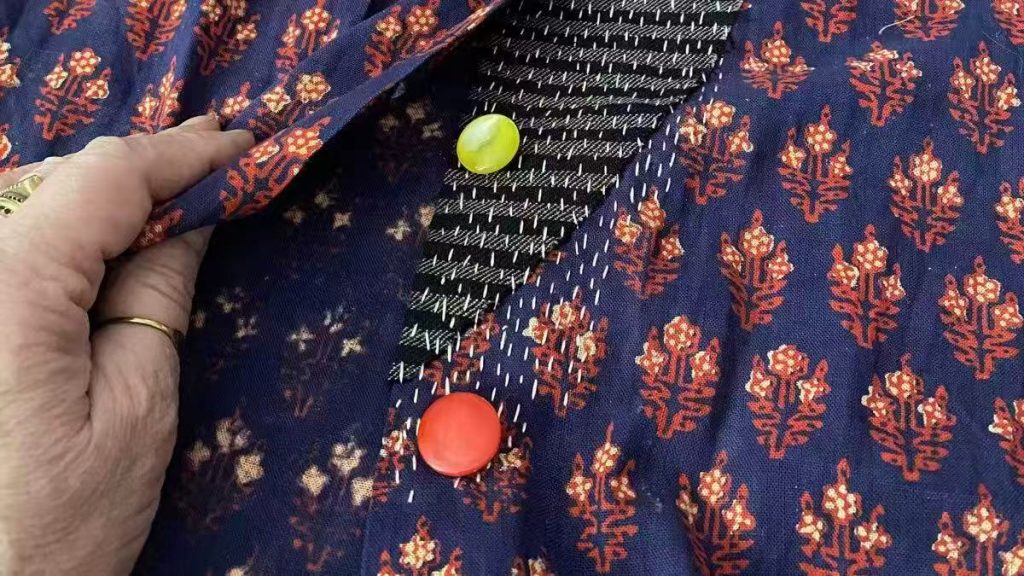

This concept coincides with the popular “Visible Mending” concept among young people today, which involves adding personal creativity to damaged clothing and decorating it into a unique design. As this trend grows, more and more people are joining the ranks of repairing old clothes. This approach is not only an environmental behavior, but also an attitude expression: not covering up the damage, but actively showing the “scars” of the clothing and giving it new life through creativity. It no longer pursues “seamless” repairs, but intentionally highlights the repair marks, even transforming them into unique decorations.

Across the UK, from community repair cafes to street patching, more people are challenging fast fashion by repairing clothing and embracing a more sustainable lifestyle. Sewing is gradually evolving from a practical skill to a cultural expression with goals and beliefs—it is a silent resistance that unfolds needle by needle.

Nevertheless, according to a survey released by the British Heart Foundation in the “Big Stitch Campaign,” about 57% of Britons said they would not sew or lacked confidence. Street patching “is a response to this reality, helping the public master the basic skill of patching through inclusive and friendly means.”

“With the development of the times, sewing is no longer a necessary skill in life but has become an ‘extra skill.’ The situation now is completely different from before,” Suzi said. “In my grandmother’s era, people had strong sewing skills and could only save money by repairing due to financial difficulties. But now, sewing is only a small part of the school curriculum, and many children will hardly use it again when they grow up.”

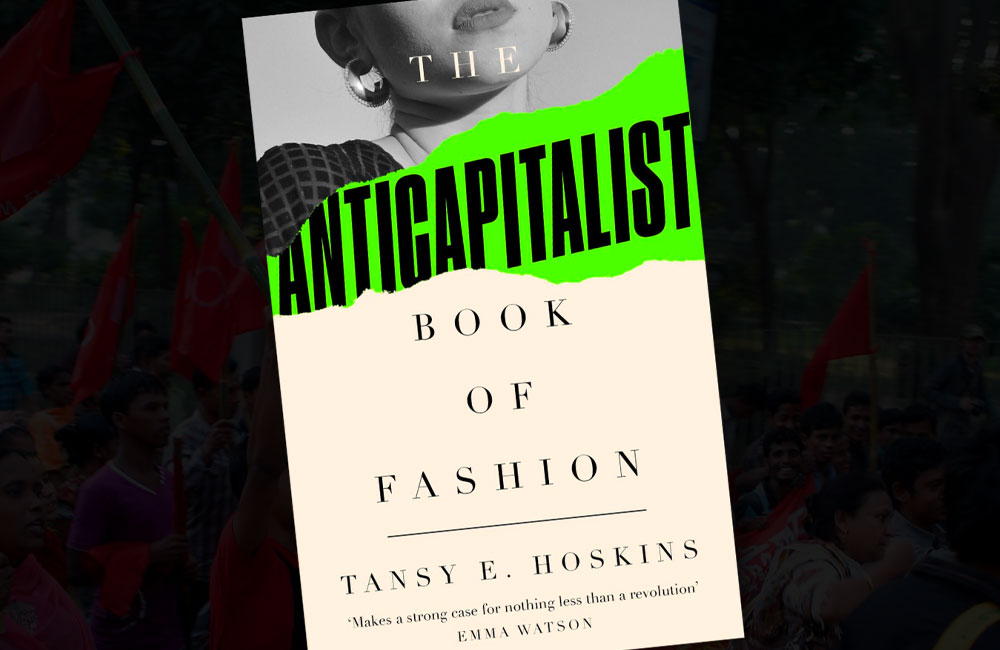

Fashion psychologist Tansy Hoskins analyzed that the fashion industry intensifies society’s pursuit of “perfection” by constantly spreading idealized body and clothing images. This mentality leads people to view wear and tear or marks on clothing as flaws, believing that once clothing is damaged or has holes, it loses its value, and therefore tends to discard it directly rather than attempt repairs.

Moreover, in the clinical research report “An examination of emotion dysregulation in maladaptive perfectionism”, it is also pointed out that those who have a tendency towards “negative perfectionism” tend to fear failure if they fail to meet ideal standards in their work. Therefore, they often choose to avoid it in various ways, such as not trying. This is why they know clothes can be repaired, but when they think about the possibility of imperfect repairs or errors during the sewing process, they would rather throw them away than take action.

But Suzi believes that the process of repairing itself contains the important concept of “accepting mistakes.” She said, “We are always told to be brave enough to make mistakes because that is the way of learning. True learning cannot be smooth sailing; only through making mistakes can people grow and learn to solve problems in different ways.”

In her view, repairing clothing is a process of embracing imperfection and learning from mistakes. When we face a damaged or stained piece of clothing, choosing to use creativity to repair, decorate, and reshape its appearance is not only restoring its function but also giving it new life and story. “I hope more and more people can understand this, especially young people,” said Suzi.

This shift in mindset actually echoes the trend of the entire fashion industry increasingly emphasizing sustainable development. In recent years, the concept of circular fashion has gradually become a focus of industry attention. From fashion education to design practice, sustainability is no longer a peripheral issue, but has been incorporated into the core value system. Suzi said, “Nowadays, most fashion schools are incorporating sustainable fashion courses at the undergraduate or graduate level. Many designers and students are actively addressing this challenge: they will consider how to make the clothing they design easier to recycle, or how to turn waste into fabric. Some people even choose more traditional but environmentally friendly production methods to reduce carbon emissions or waste.”

“Despite the challenges, creative workers have the ability to find solutions, and universities are also cultivating a new generation of designers to prepare for a more sustainable fashion future. We see various efforts happening from all directions. Universities are doing a great job in cultivating the next generation of designers who will shape the future fashion industry. But to be honest, I don’t think the problem lies in creativity, at least not what I see. Creative workers are usually good at solving problems,” said Suzi.

In the era dominated by fast fashion, Street Stitch is like a quiet rebellion. It reminds us that fashion doesn’t always have to be brand new; on the contrary, it can be revitalized through repair, reuse, and recreation. This movement not only brings environmental issues into the public eye, but also inspires more young people to pick up sustainable living skills and reshape the relationship between people and clothing with creativity and action.

Driven by this philosophy, “street patching” is not only a movement about fashion and sustainability, but has gradually evolved into a warm practice that connects people with themselves and society.

“I don’t think clothes themselves are that important; what really matters is the part beneath them, the part within us—we should focus our energy on that. At the same time, I firmly believe that sewing has a strong healing power. Sewing is not just about repairing clothes; when we help others, we are also healing ourselves. Whenever I feel the need for self-care, sewing always brings me peace,” said Suzi.