What happens when young players are introduced to rugby culture through the clubhouse before they’re even old enough to drink?

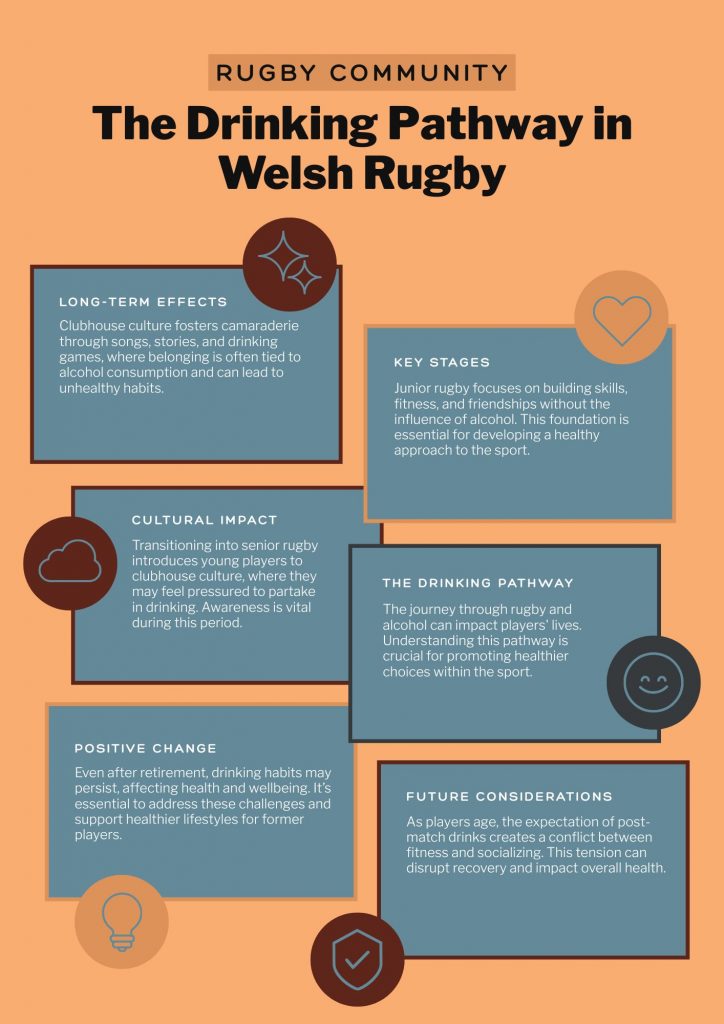

For many young players in Wales, joining a rugby club is about far more than the game itself. It’s about belonging, finding a place in a team, in a community, in a tradition that stretches back generations. But for decades, that tradition has been intertwined with another, more complicated legacy: alcohol.

The clubhouse is at the centre of this culture. It’s where players gather after matches, where the stories are told, the pints are poured, and, for better or worse, the bonds are built. For some, it’s a place of mentorship and camaraderie. For others, it’s the first step into a drinking environment they may not otherwise have encountered so intensely at such a young age.

Rhydian Collins, current chairman of Abercwmboi RFC, an amateur club, says that while socialising is a vital part of the game, it’s important to recognise the dynamics at play when teenagers make the jump into senior rugby. “I would much rather see 10 or 12 of our players sitting here having a couple of pints, being supervised, than being in a field somewhere drinking themselves silly.”

Anthony Meredith, a long-serving committee member and safeguarding officer also at Abercwmboi RFC, echoes this point but stresses that awareness of alcohol often begins much earlier than many assume. “Children up to the age of nine or ten probably don’t even realise what their parents are doing, but around 11 or 12, as they move into adolescence, that’s when they start to notice people drinking and the effects alcohol has.” For Meredith, the issue is less about exposure in itself and more about how clubs create safe environments. “In a rugby club, you look after your own. It becomes like an extended family, and people will try to intervene before things go too far.”

Andrew Misell, director for Wales at Alcohol Change UK, has spent years examining the relationship between sport and alcohol, and says the two have become “deeply woven together” in public perception. “There’s something about letting go,” he says. “When you go to watch a sport, it’s leisure time, you’re away from responsibilities. That can be a great thing, to relax, to cut loose, but there comes a tipping point when the drinking dominates, and it starts to spoil the game for those around you.”

This tipping point is something Misell says can be observed both in the stands and in the clubhouse. He recalls being told by officials that complaints about drinking games in community clubs are a regular occurrence. “There’s that tension between the people who love it and the people who really aren’t enjoying it,” he notes. “I’ve spoken to people who genuinely believe they’re introducing young players to a ‘sensible’ drinking culture, and then in the next sentence, they’re describing the drinking games. Those two things don’t quite match up.”

The idea of introducing younger players to alcohol in a controlled environment is a divisive one. Collins understands the arguments but stresses the importance of balance. “I think it’s just giving them a bit of ownership and allowing them to be treated as adults.” Meredith is more pragmatic, recognising the legal line but also the reality that many young people will have their first drink inside rugby clubs. “My personal view is that in a controlled, safe environment, a sip now and again is far better than drinking behind a shed in secret.”

Misell, however, points to research showing that early exposure to alcohol is not necessarily protective. “All of the research indicates that introducing young people to alcohol early is not the best way to get them to use it carefully,” he says. “The most important thing is building relationships of trust, explaining what alcohol is, why adults drink it, and what the boundaries are.”

This, he suggests, doesn’t mean stripping away the social side of rugby, but it might mean rethinking how that social side is built. The ‘bonding through the bar’ mentality is still deeply embedded, with players and coaches often convinced that a few drinks together is essential for team cohesion. Misell isn’t so sure. “Exactly the same issue comes up in the armed forces,” he says. “Units that drink together can be more effective, but the question is, does that bonding always have to be around alcohol? There might be other ways to build friendship and trust aside from drinking together.”

For some young players, the clubhouse is a safe space to grow into the sport, to meet older teammates and learn from them. For others, it can be intimidating, an unspoken expectation to join in, to keep pace. Collins acknowledges that not everyone will thrive in that environment. “With support, it’s just managing and identifying those who are not comfortable being surrounded by drink and putting an arm around them.”

Meredith suggests that while drinking was once a “rite of passage,” the culture is shifting. “Twenty or thirty years ago, it was seen as essential, you did your yard of ale or your pint, and that’s how you became part of the team. I don’t think it’s essential anymore, and if someone doesn’t want to drink, they’re not forced.” This generational shift is something Misell also identifies, pointing to a group of 18- to 25-year-olds who simply aren’t that interested in alcohol. “If your club is heavily focused on alcohol,” he warns, “there’s a risk those young people won’t come near you, or they’ll feel pressured to join in when they do.”

The persistence of rugby’s drinking traditions is partly down to history. As Misell points out, “The historian John Davies identified a point around the mid-1970s where the stereotype of the typical Welshman went from being a teetotal chapel-goer to being a heavy drinking rugby fan. Rugby union in Wales, unlike in England, was always a working-class game, associated with the pits, with masculinity, and with traditional notions of being able to hold yourself on the pitch and also hold your drink.”

That stereotype, born in an era when coal mining and heavy industry shaped both the economy and the community, has survived long after the collieries closed. On an international match day, Cardiff still transforms into what Misell describes as a “carnivalesque” environment. “You’ll see people who would normally be quite straight-laced, but a big event like that gives them permission to relax. I can totally understand why people want to do that, it’s just that every now and again it goes a bit too far, and someone gets hurt, someone gets abused, someone falls over.”

The same mindset filters down into community clubs, where the match-day ritual often extends well into the night. For a 17- or 18-year-old moving up from youth rugby, the culture shock can be as much about the bar as it is about the standard of play. Collins says that the club environment should offer guidance, not pressure, and warns that the wrong kind of introduction can alienate players before they’ve had a chance to settle in. “Letting them know it’s okay if they don’t want to drink.”

Meredith sees this cultural evolution clearly, especially among parents and younger coaches. “People under 35 are far less oriented towards drinking culture, but they’re also less oriented towards rugby club culture as a whole. They just turn up, coach, and go. That lack of buy-in is as much of a challenge for clubs as alcohol ever was.”

Part of the challenge, Misell suggests, is recognising that alcohol is not the universal “includer” it’s often assumed to be. “We think of it as the thing that brings people together, but it can also be a big excluder, for families with young children, people whose religion or culture doesn’t allow for alcohol, or those who just don’t like being around drunk people.”

The conversation about moderation is slowly growing, helped by generational shifts. Misell highlights that younger adults in Wales are already drinking less. “There’s a fairly substantial body of young people who are just not very interested in alcohol,” he says. “If your club is heavily focused on heavy drinking, you risk putting them off entirely.”

This isn’t about tearing down the clubhouse tradition. Both Collins and Misell recognise its value as a social hub, a place where players can connect with each other and the community. Meredith adds that the “ideal” culture is one where choice is protected. “In a perfect world, people would come in after training, enjoy each other’s company, and decide for themselves whether that means a pint, a coffee, or a soft drink. The key is that nobody should feel forced.”

For some clubs, steps are already being taken in that direction. Misell recalls one that installed a coffee machine and “were pleasantly surprised that people were turning up who didn’t previously show up at the club very often, because they liked socialising there but didn’t really want to drink beer.” It is a small example, but one that points to how social spaces can adapt without losing their sense of belonging. Other clubs have trialled family days, alcohol-free socials, or partnerships with local health bodies to promote wellbeing alongside the community. These experiments suggest that the bar need not be the only entry point into rugby life.

But there is also an institutional layer to all this. The Welsh Rugby Union’s role in shaping the drinking culture is complex. While not the focus of this feature, it looms in the background, the governing body balancing sponsorship income from alcohol brands with efforts to make the game more inclusive. Misell says he believes “there’s a lot of goodwill” in the WRU to improve rugby’s image, but admits “it’s going to be a long job, managing the relationship between the game and alcohol is part of that.”

Collins, however, was blunt in his assessment: “We don’t get a lot out of the Union at all. There’s nothing I’ve ever heard of or seen regarding drinking culture. There’s no training or workshops available. I’ve never been asked if I’d like to attend or if I’d want any training, especially as chairman or head figurehead of the club, to broaden my horizons on it. I’ve never received anything.”

Meredith agrees that the WRU’s alcohol ties are difficult to ignore. “If the Union plasters kits and posts with alcohol branding, it puts it in your face all the time. Rugby shouldn’t be tied so tightly to breweries; there are other sponsors out there.”

It is a sentiment that highlights a gap between national ambitions to grow and protect the game and the reality on the ground. While the WRU promotes family-friendly initiatives and community engagement, there appears to be little formal guidance on managing alcohol within clubs, leaving most to set their own standards or to carry on with the traditions they’ve inherited.

What that might look like in practice is still unclear. Misell references the “Good Sports” programme in Australia, which worked with clubs to make alcohol less central without banning it outright. He says similar initiatives in Wales could help clubs keep the best of the clubhouse tradition while making it more accessible to those who don’t drink.

For now, the responsibility lies with individual clubs to shape their own culture. Collins argues that the strongest teams are those where every player feels equally included, regardless of whether they drink or not. Meredith imagines a club environment where players “have a laugh, enjoy each other’s company, and then go home safely,” with choice, not pressure, at its heart. Misell offers a sharper warning: “If the only way you can build a team is by drinking together, then your team will only ever include people who are willing to drink at that level. And you might be losing out on some really good players because of it.”