Global streaming platforms are failing Welsh-language artists. Can a homemade gig map give the scene the visibility it deserves?

On a summer morning, Ceridwen Hughes-Jenkins sat over her laptop in a café, a familiar frown creasing her brow. Her mission was to find a good Welsh-language gig to travel to for the weekend. But she gradually realised it was a chore.

She has spent hours scrolling through different social media feeds and checking the individual websites of scattered venues. Sighing in frustration, she pushed the laptop away to take a break. As she looked up, her eyes caught something on the cafe’s notice board. Tucked between local ads was a small paper flyer for a gig happening that Saturday.

This is a familiar story for many Welsh speakers. In an age of digital connectivity, the search for their own culture often relies more on luck and paper flyers. This frustration is not just an inconvenience for fans but a critical barrier for the artists themselves.

Martha Owen and her brother Jonna were once among them, caught in this frustrating cycle. As a musician herself, playing in the Welsh-language indie band Brwmys, she felt this disconnect from a dual perspective.

“Welsh language gigs are a big part of our lives,” she says. “But we kept finding ourselves saying to our friends, ‘Oh, I didn’t know about that gig!’ We realised there was so much happening that we, and others, were missing out on.”

She claimed that the disconnect between creators and consumers stemmed from a lack of information flow. The fundamental problem was a failure of marketing rather than a lack of quality content.

For her, the ultimate mission was to change perceptions and show the world that the Welsh language is not a historical relic, but a vibrant and living culture. The sister and brother team decided to create an interactive platform to solve this issue.

“Live music is the best way to promote a language, because it can do something school policies can’t, it can make it [Welsh language] cool,” Martha says with a grin.

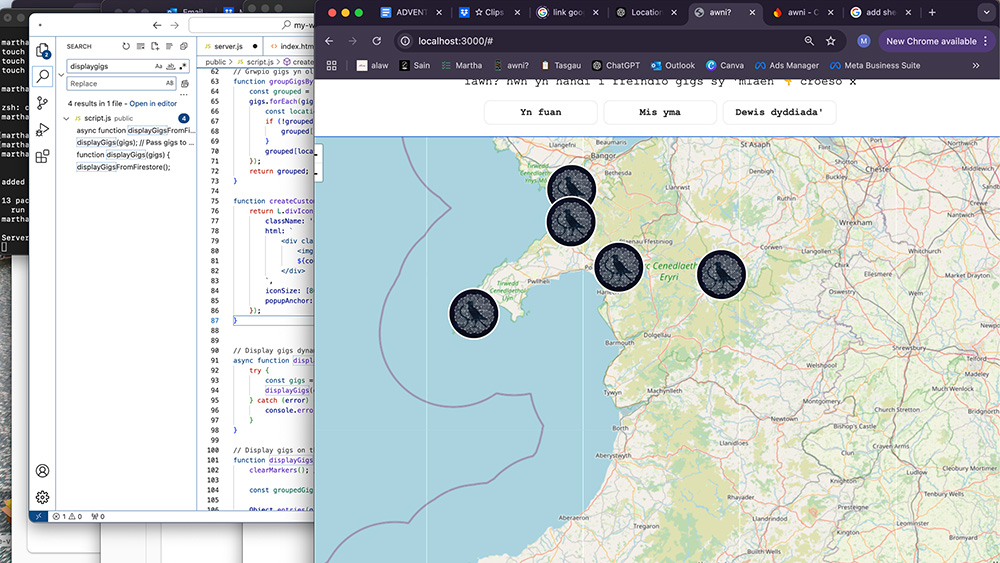

But the path from idea to reality was daunting as neither of them had coding skills and the budget was too small for a professionally built app. They subsequently decided to build the website themselves with the help of ChatGPT.

“I had no idea of how I wanted it to look, just sort of a wireframe layout type of idea. I would describe the layout I wanted, and then it would come back with the code, more or less,” Martha says. “There were a lot of improvements to be done and going back and forth, so it did take a long time.”

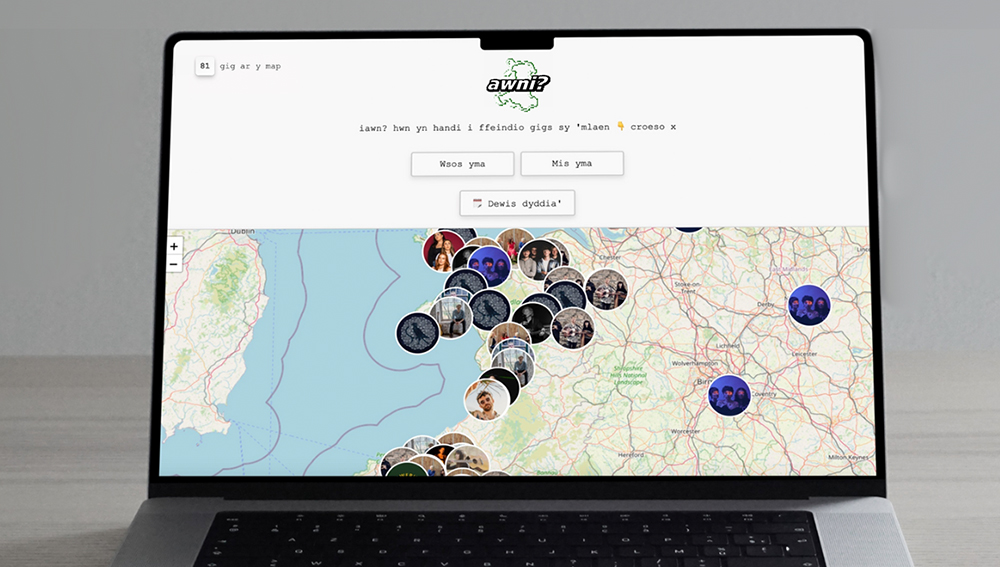

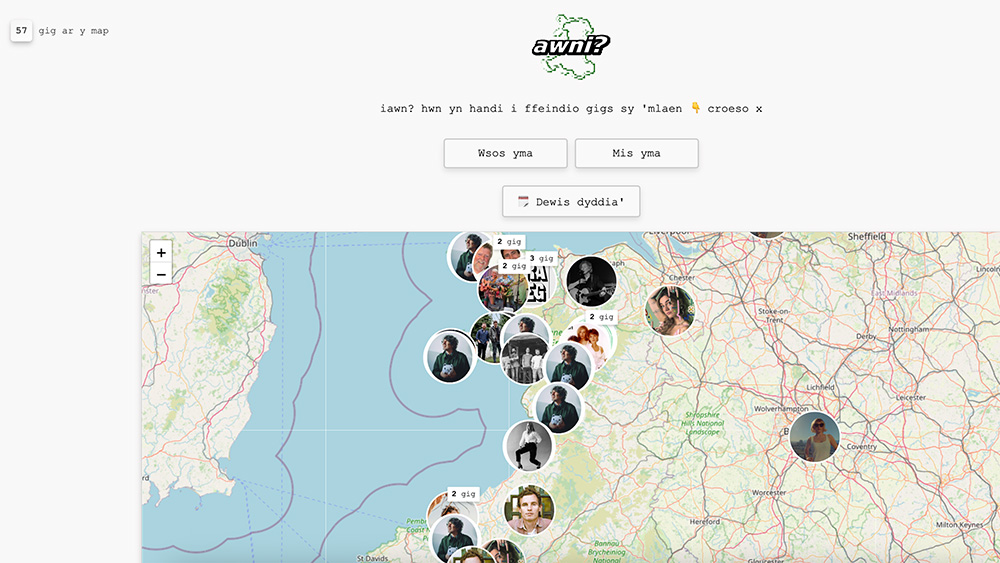

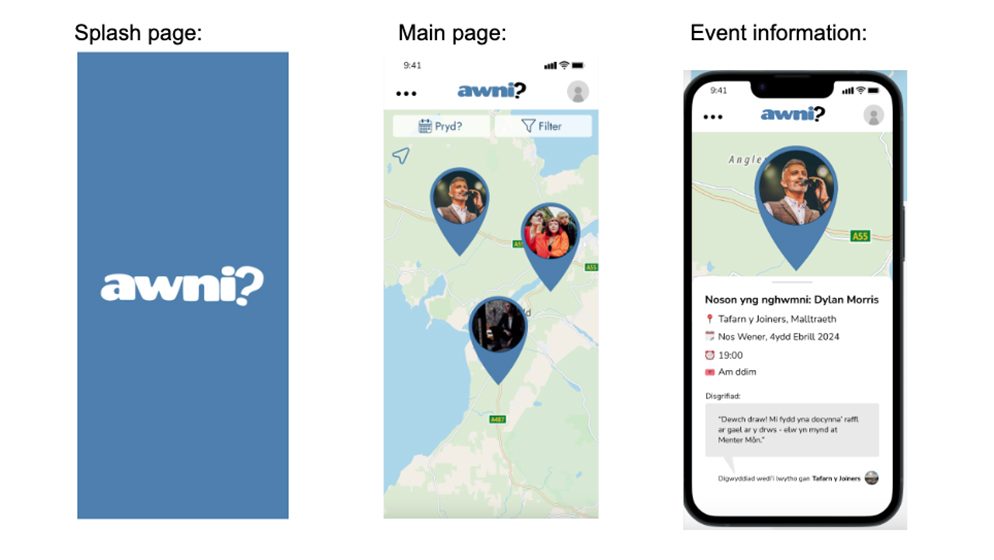

The learning curve was steep, but Martha found herself gradually absorbing coding concepts through this AI-assisted approach. After months of trial and error, the brother and sister team finally designed a website called Amni [we will go], a homemade website that maps Welsh-language gigs across Wales and beyond.

The platform’s design is intentionally simple, but its features are thoughtfully tailored to the needs of the Welsh community. Users can click on a pin to access all essential details, including the date, time, venue address, artist lineup, and a direct ticket purchase link.

“The organisation of the gigs was great, but they weren’t getting the word out enough to push tickets,” Martha says. “So we thought it would be a great idea to have one central platform that you could go to to see everything in one place.”

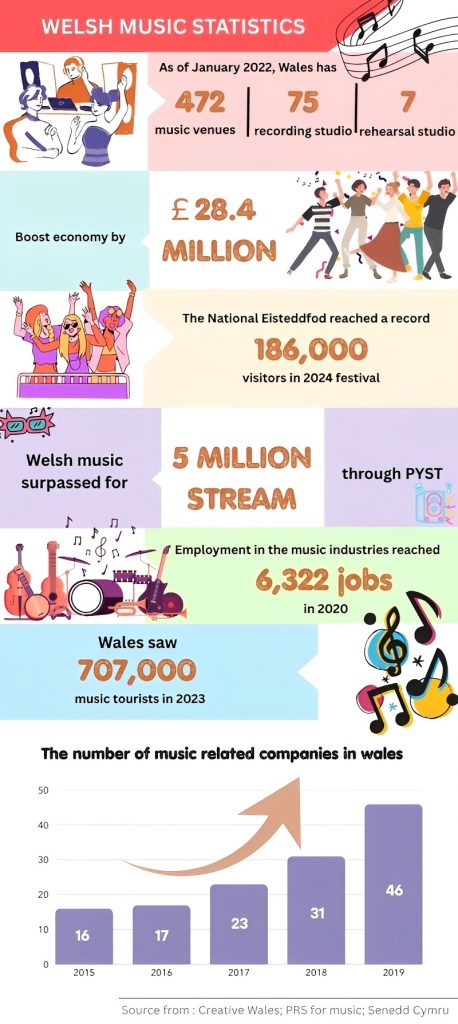

The need for a platform like Amni highlights a deeper, more systemic problem facing all minority-language music in the age of streaming and algorithm-driven discovery, such as Spotify and Apple Music.

Dr. Joseph O’Connell, a music lecturer at Cardiff University, argues that the algorithms of giants like Spotify and Apple Music are not neutral. He thinks a critical issue is that the platform does not allow a user in Wales to set their language preference in the same way as other dominate language users can.

This seemingly simple feature difference has profound implications for music discovery and cultural exposure.

He uses the example of an Icelandic user. He claimed that they can set their profile to Icelandic and receive around 50% of their initial suggestions in that language. But a user in Wales does not have the option to set up their account as Welsh.

“Spotify often just lazily groups all the Welsh language artists together,“ Dr. O’Connell says. “They ignore that these artists play all sorts of different music—rock, pop, folk. To me, that’s just problematic.”

This algorithmic bias not only affects discovery but also perpetuates stereotypes about minority-language music being somehow less diverse or sophisticated than English-language music.

According to a 2023 UK Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (CDEI) report on music streaming, algorithms can inadvertently reduce exposure for local and niche genres, creating a feedback loop that further marginalises already underrepresented music.

This creates what some describe as a “digital ghetto,” where a culture is visible to itself but isolated from the wider, genre-based conversations happening online.

The digital struggle on streaming platforms is only the first hurdle. The battle for visibility continues when they try to translate online listeners into real-world audiences for their gigs.

Welsh local musicians like Morgan Elwy feel the digital struggle daily. The fight for attention online is compounded by real-world pressures, like the cost-of-living crisis makes it even harder to convince people to promote his reggae music and gigs.

“I use social media all the time and I try and push my gigs as much as I can,” he says. “But you know, there’s so much traffic, so it’s hard to get your message through.”

The fight for attention online is compounded by real-world pressures, where economic factors like the cost-of-living crisis make it even harder to convince people to attend live events, regardless of the quality of his reggae music and performances.

This is where the two digital struggles intersect and compound each other in particularly damaging ways. The failure of streaming platforms to build a dedicated, genre-specific audience for Welsh artists makes the task of promoting a specific gig on social media even harder.

Artists are left shouting into a void and trying to reach a scattered, undefined group of potential fans who might not even know they exist.

However, the challenges facing Welsh-language music extend beyond digital platforms to the physical infrastructure that supports live music. Music venues in Wales are facing their own existential difficulties, creating another barrier for artists trying to connect with audiences.

A report from industry body UK Music in 2019 highlighted a crisis in the city’s live music scene. Nearly 35% of live music venues have closed in the past five years due to financial pressures, rising rents, and post-pandemic economic challenges.

Each closure represents not just a business failure but a cultural loss, these venues serve as community gathering places, artist development spaces, and cultural hubs.

In November 2024, the Moon, one of the most renowned venues in Cardiff, closed its doors for the last time. The venue had been operating for over two decades, hosting everyone from emerging local acts to established touring artists. Its closure sent shockwaves through the community.

What makes it worse is that it follows a series of other beloved Cardiff venues, including Gwdihŵ, Buffalo, and 10 Feet Tall, all of which have also ceased operations in recent years.

Each closure shrinks the ecosystem that supports Welsh-language musicians. This makes it harder for emerging Welsh-language musicians who relied on venues for their early gigs to perform.

It is against this backdrop of algorithmic invisibility and disappearing venues that platforms like Amni become not just helpful but vital for cultural survival.

On the day of its launch, the website attracted over 7,000 visitors, a remarkable achievement for a completely homemade platform created by two individuals with no prior web development experience.

Many independent promoters and artists took to social media to praise the platform, celebrating that it finally solved their long-standing problem of having to “go it alone.”

But the platform’s impact has gone far beyond just connecting fans to gigs. It has also revealed unexpected and valuable insights into the geography of Welsh culture that were previously invisible to policymakers, funding bodies, and cultural organisations.

“When we first launched the platform, one thing that was really obvious was just a gap of gigs in Powys in mid-Wales,” Martha says. “And that’s something when we realise it’s actually quite a handy tool as well to have, like a heat map, to see where more funding maybe need to be put.”

This grassroots success soon attracted official support. Sain, Wales’s oldest and most respected record label, quickly saw the platform’s value. They came on board to provide crucial support through the ARFOR Challenge Fund, a Welsh Government programme aimed at strengthening the economy in Welsh-speaking communities.

This partnership provided Amni with both funding and a massive promotional push on national radio and television.

“Through them, we had a lot of PR,” she says. “We got the word out on Welsh radio, Welsh Television, and the news. Sain really helped us to get the word out.”

The journey of designing digital platforms for cultural preservation is just beginning for Martha and her brother. She sees the current website as a starting point with a more ambitious plan for the future.

“The end goal of having an app is still in the pipeline. It would be great to have lots of other features like notifications and saving gigs, and sharing them with friends and things,” She says.

But the technological expansion is only part of the vision. Martha has also identified another gap in the ticketing market.

“There used to be a Welsh language ticket website, so similar to Eventbrite, but it was all in Welsh,” she says. “It’s a shame that that’s not running now. And that’s definitely a gap that maybe we can step into.”

Additionally, Martha hopes to expand the Amni brand itself by taking it offline. “I think in the next year or so we hope to branch into organising our own events,” she says.

She also recognises that the platform’s potential extends well beyond Wales. Minority language communities around the world confront strikingly similar obstacles.

“I think the model could work in any country,” she says. “We already list gigs happening outside Wales, in England and across Europe. So I don’t see why other minority language communities, like the Catalans in Spain, couldn’t use the same model.”

Music is a universal language, breaking down barriers rather than reinforcing them. For her, the platform is not just about serving existing Welsh speakers, but also about creating bridges between communities and inviting newcomers into the fold.

When Alffa’s “Gwenwyn” became the first Welsh song to exceed 2.5 million Spotify streams, it proved Welsh music could compete on global platforms without compromising its language.

“You don’t have to speak Welsh to enjoy the music,” she says. “You don’t have to understand the lyrics. There’s always something on, so just have a look on the website and try something.”