In Karchi’s heatwaves, expecting mothers are suffering due to poorly designed buildings that trap heat. What must change to make housing cooler in a city with over 20 million people?

When a heatwave hit Karachi in 2022, Faiza was in her final trimester. It’s blistering heat seeped into every corner of her house, clinging to her skin and making the weight of her unborn child almost unbearable to carry.

Her home, an old bungalow from the 60s in one of Karachi’s oldest neighbourhoods, wasn’t built for the kind of heat that struck the city, a heat that few could have imagined, let alone designed for, back then.

Faizah didn’t have air conditioning, which made staying cool harder. “There was a bucket filled with water in the bathroom,” she says. “Whenever I’d feel too hot, I’d just go and pour water on myself, all over my clothes. The feeling of wet clothes on my skin felt so good, at least until the clothes dried up.”

When the government warned people that temperatures would spike even further, Faizah was only a few weeks away from labour. She begged her husband to book a private room at the hospital, one with air conditioning, so she and her newborn could rest properly after the delivery. She gave birth to a healthy boy in June.

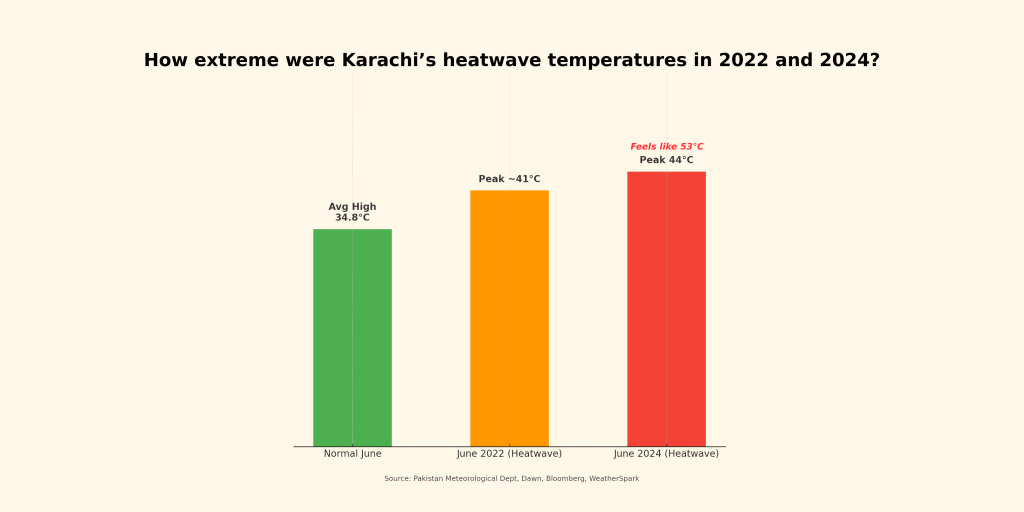

Pakistan’s largest city has experienced severe heatwaves driven by climate change over recent years. One of the deadliest ones occurred in 2015, when temperatures rose above average, resulting in at least 1,200 deaths and many hospitalised.

The effect of a heatwave is amplified by the city’s lack of green spaces, such as parks, and the presence of buildings that trap heat. Whether it’s homes, offices or schools, the materials used to build them, as well as the methods of construction, turn these spaces into ovens when the mercury rises.

Homes heat up quickly, and women are particularly affected. Research shows that Pakistani women spend most of their time indoors, busy with tasks like cooking, cleaning, washing, and caring for children or the elderly.

If a woman is pregnant, she may be more vulnerable to heat in a stiflingly hot home. Intense heat can have a profound impact on a woman’s pregnancy.

Dr Jai Das, a public health researcher at the Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, is currently studying these impacts on pregnant women. “There is immense impact, from the very start, because the child is not developed enough,” he says. “Heatwaves can lead to low birth weight, stillbirths or premature births.

“Low birth weight can impact a child’s cognitive development., which can affect their future potential. Some evidence is also coming up, which suggests that because of low birth weight, children are more prone to infectious diseases very early in their lives.”

The mother, too, may suffer from severe dehydration, hormonal issues, high blood pressure or gestational diabetes.

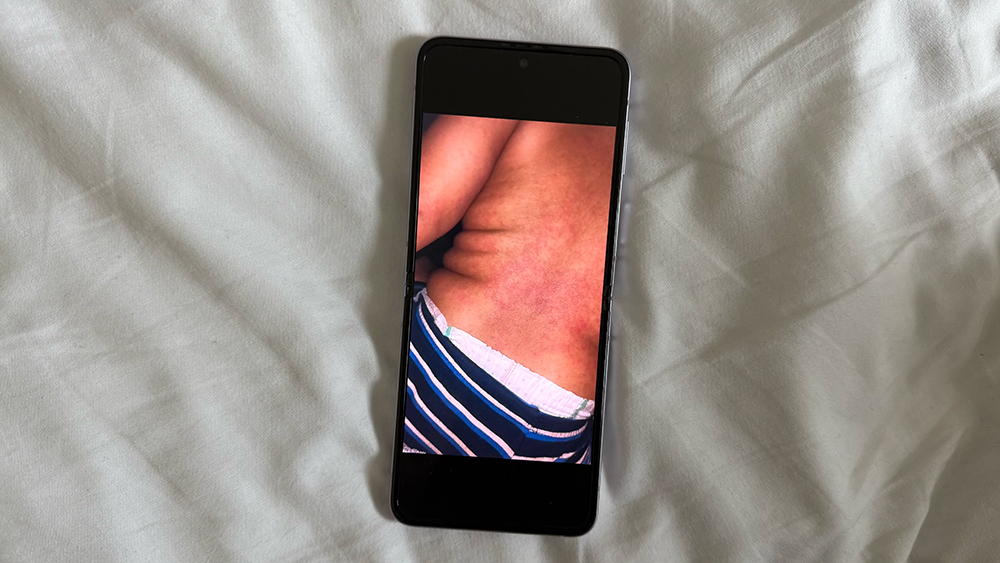

Faizah remembers how overwhelming the heat grew for her during pregnancy. “I’d start crying because of how hot it got,” Faizah says. “My back was covered with heat rashes. I’d get them on my face and my neck. The only solution we’d have for that was prickly heat powder.

“I can’t even remember how many bottles of powder I went through. My husband would try to stop me, saying we don’t know if the prickly heat powder is harmful to the child, but I wouldn’t listen. I’d tell him, ‘Don’t talk to me because you have no idea how difficult the heat is for me right now.’”

Why are the indoors getting hotter?

Karachi sits on the edge of the sea in Sindh, a province that has always known hot summers.

Traditionally, communities dealt with the heat through architecture that utilised the sea winds. One practice was building windcatchers, or Manghs, that brought the cool air inside homes. These were commonly found in coastal towns, including Karachi, before the British colonised Sindh.

Arif Hasan, a Karachi urban planner and architect, talks about how there was also a conscious practice of placing windows in specific places during construction to help cool air come indoors.

“To keep homes cool in the summer, you always had an opening to the west from where the cool breeze came in, and you had a slightly larger opening to the east so that the warm air could go out,” he says.

These practices have largely been abandoned today. “The developer wants to get as much money out of a piece of land as he can, and so if you disregard these old manners of construction, of design rather, then you get more space to sell.”

While the traditional ways are being cast aside, newer, climate-smart building methods remain ignored as well. “Heat affects all the construction in Karachi because we have not built them to withstand high temperatures,” says Arif. “What these buildings are missing is insulation designed to protect against high temperatures while slowing down the transfer of heat.

“In addition to that, there is a dearth of plantations, because where you have trees, temperatures are considerably lower than where you don’t have trees.”

With a population exceeding 20 million and insufficient housing, real estate developers have resorted to building high-rise buildings to maximise occupancy in a limited space. Apartments with two or three rooms will sometimes have up to 10 people living inside. These structures are frequently poorly ventilated and lack proper insulation from heat.

Faizah used to live in a high-rise apartment before her marriage. “It was a very congested apartment building,” she says. “It had a very tiny kitchen. We had a huge exhaust fan in the kitchen to suck the heat out while cooking, but it barely helped.

“It felt like you couldn’t breathe in the heat because other tall apartments surrounded us, and no breeze could come through. The only way to feel the breeze was to exit the apartment complex and head to the main road.”

Densely packed settlements

High-rise apartments aren’t the only buildings impacted by severe heat. It also affects poorer neighbourhoods where small settlements are closely packed together, separated by narrow passageways that prevent the breeze from flowing through and reaching indoors.

When a family outgrows these settlements, many cannot afford to purchase larger houses. They often find it more cost-effective to add extra floors to their current premises. However, this is frequently done without following government-regulated planning and design to keep indoor areas cool.

During the 2015 heatwaves, most of those who died or suffered heat strokes lived in such a neighbourhood. In one area, Rohri Goth, more than 15 people reportedly passed away, most were women and children.

Many women in Pakistan face cultural restrictions that limit their access to public spaces compared to men. So, if their homes become too hot, women will have little choice but to stay inside the settlements and endure it.

“What you see in cities like Karachi is that there are electricity shutdowns for 8,10, or 12 hours at a minimum in these areas,” says Dr Jai. “If you go there, you will see men sitting outside, trying to cool themselves down in the open air. The children will be playing outside too, but the women, because of various factors, cannot go out.

“Even in extreme heat and humid environments, without any electricity, they are trapped inside their houses. Our social and cultural settings make women more vulnerable to heat stress.”

Whether it’s apartments, small settlements, or old bungalows, pregnant women inside don’t only face the heat; they also cook in it. Many spend hours in the kitchen, standing before a hot stove, often not just for themselves but for their baby, who needs proper nutrition to develop.

This was Faizah’s motivation for stepping inside the kitchen as well.

“It was a really difficult thing to do,” she says. “I’d splash water on myself repeatedly to keep cool while cooking. I’d cook food in mustard oil or ghee, and that created a lot of heat as well, but I did it because if I ate something good, then the baby would benefit from it. So, I cooked despite the difficulty.”

Faizah may have mustered up the strength to cook in the heat, but she lost her appetite for piping hot meals. “During my pregnancy, I preferred making cold sandwiches,” she said. “I didn’t want hot tea anymore. I wanted to eat and drink cold things. I’d make sharbat or mango shake, or banana shake.

“I started drinking a lot of ice water. Even today, if anyone comes and sees my freezer, all they’ll see are bottles and bottles of frozen water. That’s the extent to which we need cold water to beat the heat.”

Heatproofing homes

Something must be done to keep Karachi’s homes cool during a heatwave. The solution lies in renovating old buildings to keep them cooler inside. As an urban planner, Arif believes this is as important, if not more, than constructing new buildings that are heatproof.

“One thing that has to be understood, and which is normally not understood by climate experts who keep visiting us, is that the issue is not what you build in the future, but how you retrofit that which already exists,” he says.

“You need to create cross ventilation, and you need to create insulation. This is for both upscale houses and poor settlements.”

Universities can play an essential role in creating this awareness of retrofitting homes amongst the public. But the onus of making the city more resilient against the heat doesn’t just fall on the public. It falls on the authorities as well.

Although the local government has developed a detailed plan that outlines emergency response measures before, during, and after a heatwave hits, retrofitting buildings for heat resilience is not a central part of the strategy.

Making homes heat-resilient doesn’t always require expensive or complicated fixes. Dr. Jai has studied how homes, especially in densely packed, low-income settlements, can be modified, and he’s seen how even simple changes can make a noticeable difference.

“We have seen a 2 to 3 degrees decrease in the temperature inside homes,” he says. “We’ve done this by installing reflective panels on the roofs, which absorb the light to create electricity but also reflect it away. We used chuna on the walls, which is the local word for lime paint, to keep homes from absorbing less heat.

“We have also tried shading roofs with frames made from locally available bamboo, and covering those with green nets. This also helps to shade the roofs from the heat.”

Allowing Karachi’s breeze into homes is crucial for making them as heat-proof as possible. “We’ve tried to create cross-ventilation in homes. That means creating windows in walls that didn’t have them before so that air can move in and out,” says Dr Jai.

But not every window in a house helps keep the space cool. “We’ve actually asked families to keep certain windows completely covered,” he says. “These windows have glass panes that are directly exposed to the sunlight, and they let in a lot of heat. At least with the windows covered, the sunlight won’t come inside as much.”

Faizah has little hope that the authorities will implement measures like these to help make homes more resilient against heatwaves. It’s every man, woman and family for themselves, she says, just like it has been during every other heatwave that’s hit the city these past years.

Her son, Tehmeed, who is now three, struggles with the heat alongside her at home when summer temperatures spike.

“Tehmeed feels really stressed because of the heat,” she says. “He roams around the house in his diaper the entire day because of the heat. If he’s wearing anything more than that, he asks you to take off his shirt.

“He knows that I’m usually wet because I’ve splashed water on myself. So, he’ll come to rub himself on my wet clothes to cool himself off, and then he’ll go to sleep.”

Faizah wonders about her son’s future in Karachi. Will the city’s climate crisis intensify in the coming years, making life even harder for future generations than it is now?

She reminisces about the Karachi he never saw. “It used to be a lot windier in the city before,” she says. “So windy that the wind would push you back a step or two when you’d be walking. Now, you don’t get those kinds of winds anymore. You don’t get those kinds of rains anymore.

“During my school days, we’d play in the grounds after classes. Now that’s not possible. It is so hot that it’s better for the kids to come home as soon as possible. Come home, take a bath, and cool yourself down.

“All we’re leaving behind is a concrete jungle that burns in the summer.”