Struggling with body image can feel exhausting and positive thinking doesn’t always help. Can shifting the focus from how the body looks to what it can do be the way forward?

Marley zips up her jacket, fastens her helmet, and swings her leg over her bike. She sets off through the forest, winding through rugged paths and beaming down long open stretches, with the wind catching her smile.

Behind her, a documentary crew follows, capturing her every move. But the film is about more than just cycling, it is about Marley celebrating her body. Marley practises body neutrality and brings this idea into the cycling community, that often overlooks plus-size people, and onto her social media platforms.

Marley Blonsky, a content creator and co-founder and executive director of All Bodies on Bikes finds body neutrality helpful in improving her self-esteem. “Body positivity asks you to feel positive about all aspects of your body, which is unrealistic for, I think, everyone. We all have little bits that we don’t love or get frustrated with,” says Marley. “And so, body neutrality acknowledges that and gives room, but also says, no matter how I feel about my body, I still love who I am as a person.”

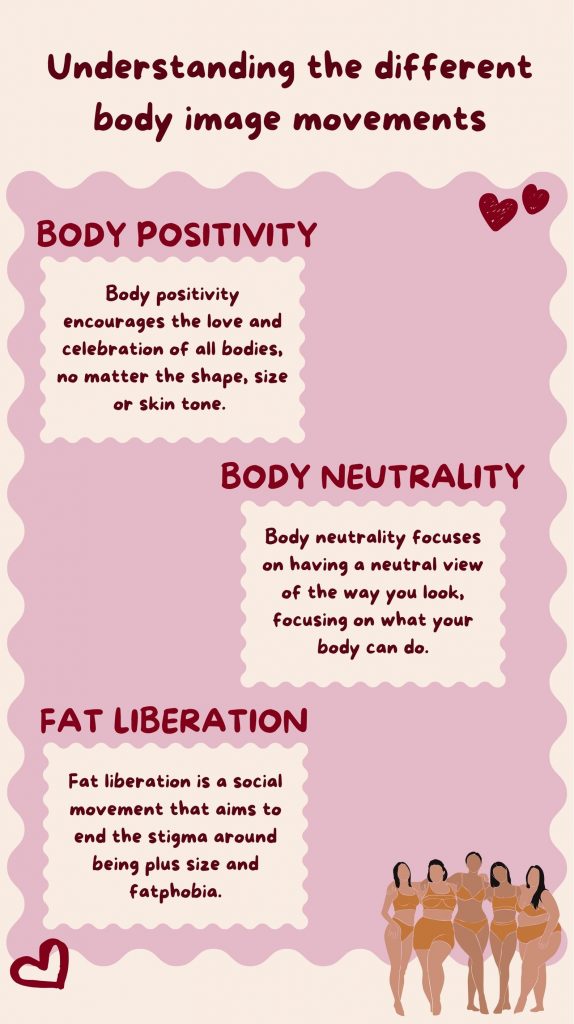

Body positivity has faced backlash in recent years for its unrealistic and oversimplified message. The movement often misses the complicated feelings people have with the way that they look.

This is where body neutrality comes in, encouraging people to have a neutral view of their appearance. Instead of relying solely on the way the body looks, the idea focuses on what the body can do.

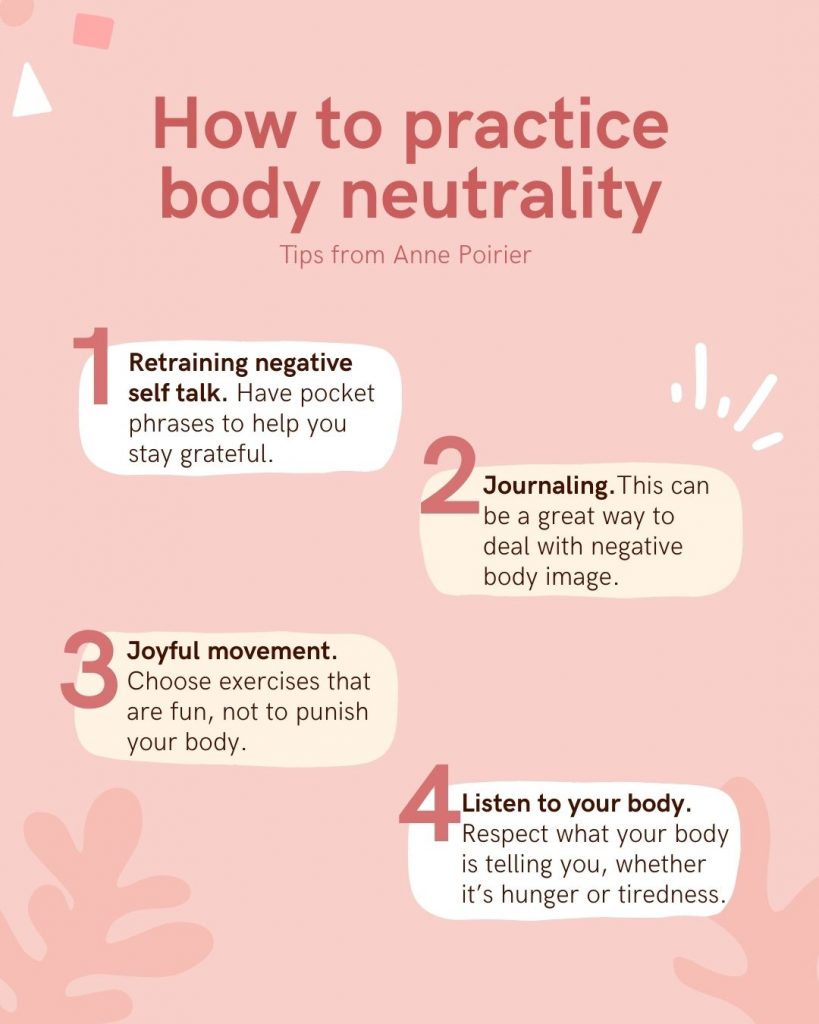

Anne Poirier, a body image coach focusing on eating disorders popularised the idea. Anne first used it for herself and now teaches it to others facing body image struggles. “When I heard the term body neutrality, I kind of took hold of it as this little resting place that I can sit in that’s not buying into hating my body, and it’s also not buying into loving my body,” says Anne.

Around 60% of adults feel unhappy with their appearance with just over one in five adults struggling with their body image as a result of social media, according to Mental Health UK.

Parts of the online world are filled with dangerous content. Trends like ‘SkinnyTok’ and ‘thinspiration’ content have gained a lot of attention. Influencers who play a part in the trends glorify eating small amounts of food and encourage being extremely thin. Now ‘SkinnyTok’ is banned on TikTok instead directing users to support resources when searching the hashtag.

Alexandra Dane, a researcher at the University College London Institute for Global Health finds that online content can have harmful effects on user’s mental health and body image. “Our findings show that social media usage is a plausible risk factor for the development of eating disorders. And, based on the scale of social media usage amongst young people, this issue is worthy of attention as an emerging global public health issue.”

But while platforms are clamping down on removing these harmful trends, the impacts remain. Hannah, a plus-size fashion content creator knows all about this. Her content is shared in pro-anorexia groups as “inspiration to starve themselves.”

Hannah says, “It’s maddening because especially as someone who, you know, is eating disorder recovery, I understand to a certain extent how the brain works when it’s just so obsessed with food and weight, and to know that my image is used to encourage people to go deeper into that really disordered eating is so sad. It is really sad but it’s so warped at the same time, I’m just like a person existing.”

The dark corners of the internet are a stark reminder of the dangers of social media trends. But when some influencers are pushing for users to obsess over their appearance, content creators like Marley are encouraging their audience to think less about their looks.

Consuming body neutrality content can have a positive impact on the way people view themselves, according to a recent study by psychologists Veya Seekis and Rebecca Lawrence.

The researchers found that the content can boost people’s mood and reduce the level of comparison with others.

The body neutrality hashtag has been used over 430,000 on Instagram compared to body positivity with 12.7 million posts. But even as a smaller movement, body neutrality has made a name for itself.

I can get frustrated with parts of my body without having that impact my overall self-esteem. – Marley

People can feel pleased with their ability to walk or dance but dislike their arms or legs, just like Marley. “Last weekend I just rode 109 miles, but I can also be frustrated that my thighs are jiggly or I have got stretch marks,” says Marley. “I can get frustrated with parts of my body without having that impact my overall self-esteem.”

Marley posts videos to her TikTok and Instagram accounts spreading uplifting and empowering messages. Like telling people to “wear those shorts, wear that dress” because “it’s your body and if someone has a problem with that then that is their problem not yours.”

For many body neutral content creators like Marley, having a healthy view of their body did not come easy. “I didn’t really have a positive mindset on my body until I’d say my early to mid-thirties. Before then, I was constantly trying to shrink myself, dieting and restrictive eating and all sorts of stuff because I thought I needed to change. It really wasn’t until I started doing the work in cycling and in the body neutral space that I realised my body isn’t the problem here.”

But Associate Professor Kate Mulgrew, Dean of Graduate Research and Researcher Development with a discipline in psychology argues that body neutrality does not exist separately from body positivity. “I think body neutrality has gained popularity with people who want something different from body positivity, but this is often based on misguided assumptions, like body positivity says that you have to like your body all the time,” says Kate. “If you go back and read the original papers on positive body image, it doesn’t say that at all.”

Anne views body neutrality separately, yet she sees that it is not a replacement. “I think they kind of lie on a continuum. The continuum is a really interesting way of looking at this whole body image piece. And if body neutrality is on that continuum, so is body positivity and body love and body respect and body acceptance and body appreciation,” says Anne. “So, I think they can certainly coexist and one doesn’t have to outweigh the other.”

At the same Kate admits that body neutrality has its limits. “There are mixed views towards the concept. Some people think that it is the new big thing that will magically change the way we interact with our bodies. I see this a lot on social media. However, others are more cautious,” says Kate.

Body neutrality has been successful for the likes of Marley and Anne. Yet it has faced some criticism for its lack of inclusivity towards disabled and chronically ill people. The primary message of body neutrality is to appreciate your body’s function. For many disabled people this idea is flawed.

Rachel Jeffery, an influencer and writer, is positive about her body even with the challenges that come with having a disability. “We should celebrate our bodies and not just over function because at the end of the day, it’s the only body you are going to have, and this body is going to help you live your life despite whatever limitations,” says Rachel.

It felt difficult to have that kind of love for it, when my body was also a site of grief, frustration and longing. – Bee

Kate does not think that body neutrality is ableist because disabled individuals can still value what their body does for them. She thinks about dancing with her niece. Kate twirls her around, with the wheels on her wheelchair spinning across the floor. They sway along to the music with both faces lit up with smiles.

“Our dancing looks very different, hers is definitely better, but she still enjoys moving her body and taking pride in that. It’s just that her body moves differently. That doesn’t mean that a concept like functionality appreciation doesn’t apply to her,” says Kate. “It’s about acknowledging that everyone has different bodies, which function differently, and may not always function the way that we like them too but recognising and appreciating that there are many wonderful things that our bodies can allow us to do.”

But for Bee, a disabled content creator, they struggle to resonate with the message. “I used to see a lot of phrases that surmounted to ‘your body does a lot for you and lets you move’, but mostly I couldn’t relate to this kind of thinking,” says Bee. “I understand the sentiment of it, in that our bodies are fighting for us. But I couldn’t love my body in that way because it was flaring up and breaking down and hurting almost all of the time. It felt difficult to have that kind of love for it, when my body was also a site of grief, frustration and longing.”

While neither body neutrality, nor body positivity is the perfect solution, they still open the doors to reframing negative thoughts. Different content creators have ideas about the way forward.

For Bee, focusing on positive body image is part of a broader step towards fat liberation. “I don’t want to just be talking about how to love my body, which feels like another unhealthy standard to place on myself, I want to be talking about eradicating weight stigma, fighting all oppression, and making space for everyone,” says Bee. “Liberation looks like freedom, and care for all of us, not just a small group of us that have enough proximity to social norms to be deemed acceptable.”

Marley agrees. “I think body neutrality plays into [fat activism] because fat people can recognise that, yeah, my body is kind of a problem at this point, but that doesn’t mean it necessarily needs to change or it doesn’t mean that I’m a bad person,” says Marley.

For activists, body neutrality is only a small step. Fat liberation takes things further. They stand up against systemic fatphobia and campaign for better access and equality for all plus size people.

Hannah believes that body positivity will come back following the fallout from weight-loss drugs. “Body positivity is going to have a massive resurgence in the next five to ten years because people have all gained the weight back. Because that’s what happens when you come off these drugs. I feel like my job at the moment is to like hunker down, remain a safe space, keep banging my little drum of your body is not the only thing that matters about you, you know you’re worth more than the weight on the scale,” says Hannah.

On her bike, Marley does not think about how she looks in her cycling shorts or worries about how her helmet might mess up her hair. She focuses on feeling the burn, the thrill of gliding down a steep hill and thanking her body for letting her do it.

Body neutrality can seep through social media and into the everyday. It shows up in the small moments. From choosing clothes for comfort without thinking about how flattering they are, or not hiding away from photos with friends and to finding peace.

The way forward might not be down to one movement. Instead, it might be a collective push to fight against the harmful beauty standards and the oppression of plus size and marginalised bodies. And for each person, it is choosing what works for them.

As Marley puts it, “I think so many people are just at the very beginning of their body acceptance journey. Even if they just stop at body positivity that’s a great thing. I think so many women hate their bodies because they don’t look like what we see in the media, they don’t look like what they think they should look like. So, if we can stop that train of thought, we’ve got to win.”