Priest appointments for churches in the UK are falling by a third since 2020. In response, foreign priests have stepped in, navigating culture shocks, building communities, and quietly sustaining the Church’s mission.

The silent corridors of the St.Peter’s Church held a surprise, leading into a well lit hall on a bright Sunday morning. Cutting through the stillness was a preaching voice which sounded warm, steady, and unmistakably foreign with its wildly different accent setting it apart from the local tones. There was this priest from India standing calmly with a light smile on his face and a spark in his eyes, preaching a homily to a church full of multicultural parishioners of the oldest catholic church in Cardiff.

Father Benny Dennis who hails from a small town in Kerala, India, did not always aspire to be a priest in Cardiff. Teaching at a seminary in Bangalore during the fall of 2020, he had no idea where his life would end up in a span of just a few years.

“Once upon a time, missionaries came to India from here. Now we are going to them,” says Father Benny, who was just as shocked when he received a call from his congregation’s leader that he needed to go to the UK. He says that since he belongs to a religious congregation he cannot deny the orders of his superiors. “If I was given a choice, I would have remained in India.”

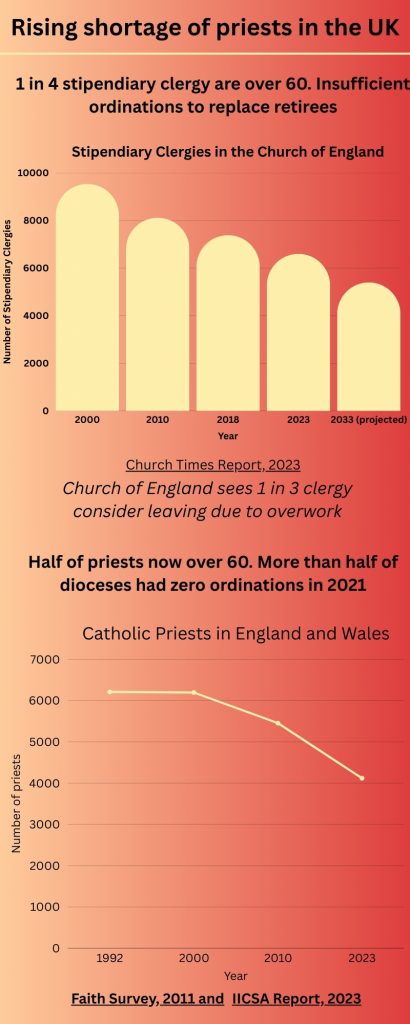

He is just one of many stepping into a growing gap. According to the General Synod, Catholic ordinations in the UK dropped from about 600 in 2020 to fewer than 400 last year, a 38% decline. The Church of England has faced a similar plunge, with stipendiary ordinances nearly halving from 2019 to 2023. With hundreds of churches left with no full-time clergy, the need for foreign-born priests has become essential more than ever.

But, Father Benny was not here without a reason. He, like many other immigrant priests, was called to fill the growing shortage of priests at many UK parishes. “I didn’t choose, they chose me,” he says.

When he arrived to serve at a parish in the UK, one of the five priests of that parish died, one went to a care home and another priest was sent back due to old age. Benny, 35, replaced the local priest who was 82 years old. A majority of priests currently working in the UK are above 70 years of age, according to the Association of Catholic Priests.

Father Chris Fuse, a Welsh priest who has been serving in the UK for decades says that it is now rare to see young men giving their whole lives to priesthood. He says the closing down of seminaries is causing more shortage of priests in the country.

“Just two years ago, we closed the seminary in Guilford. We do require more priests who are younger, because the older ones, they get weak and have to retire”, he says. “The rising number of immigrant priests has become essential because otherwise we would not be able to help the parishes keep open.”

Father Benny says that the main problem in the UK is that people are not quite interested in becoming priests. “They want to work, they want to earn, and they have got a lot of facilities”, he says.

Coming from a poor family of fisherman in India, he was inspired by the priests where he grew up around right from his teenage. He was also moved by nuns who taught him principles of Christianity in the form of catechism and showed him movies about Saint John(Don) Bosco, the Roman Catholic priest who was a pioneer in educating the poor and founded the Salesian order.

But, migrating to the UK after becoming a priest was not a pleasing experience for him. Father Benny experienced a few cultural shocks when he saw a man from the congregation drinking at a pub which was not at all normal for priests in India. “Something is bad there, but when it comes here in this culture, it is normal”, he says

He says that people here like to have their privacy which is quite the opposite of what he experienced in India where people always came to the presbytery and he was always surrounded by people to talk to. “In our place, religion is a way of life. From morning till evening you live it, here it’s not that way.” He says that he still struggles when people say that they are believers but not church-goers.

Although he says he has not experienced racism within the Church, Father Benny recalls feeling unwelcome in some public spaces, where he encountered microaggressions or felt judged based on his appearance. “When I wear my cassock, people look at me differently”, says Father Benny.

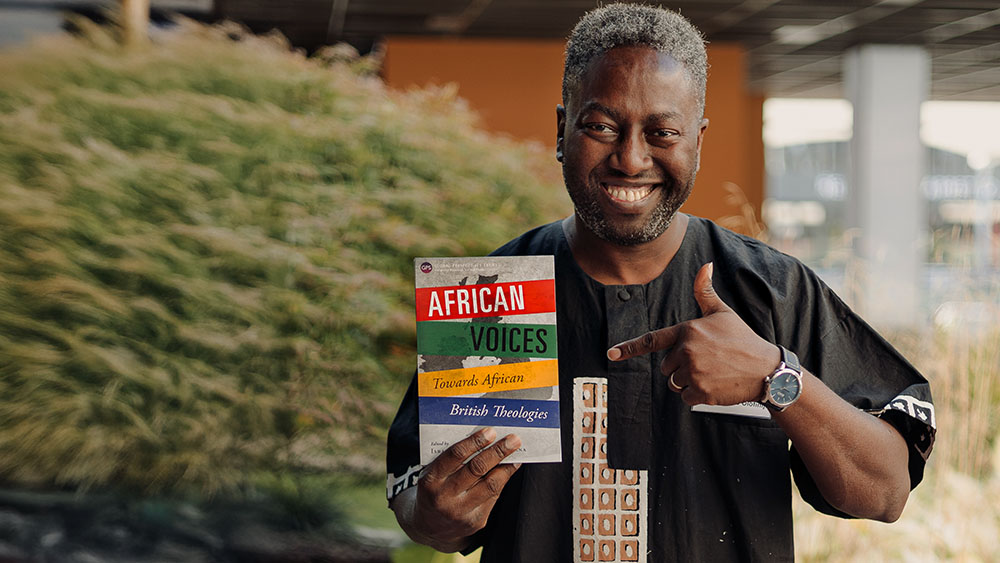

Baptist minister Dr. Israel Olofinjana, who migrated from Nigeria more than two decades ago also says that immigrant priests face discrimination not in overt name-calling, but in more insidious ways, in how immigrant clergy are questioned, in assumptions about their intelligence, and in who gets to lead.

“I call it the Guinness Church,” he says. “White at the top, black at the bottom.” Even in diverse congregations, he says, leadership often remains disproportionately white and British-born.

According to a report in the Christian Today, 92 per cent of clergy, and 94 per cent of senior clergy, are white and British in the Church of England despite Black, Asian and other ethnic minorities making up about 15% of the congregation. Another finding by the Anglican church says that the total number of UKME/GMH(UK Minority Ethnic/Global Majority Heritage) bishops can together be counted on one hand (five out of 111).

The number of UKME/GMH deans, archdeacons, and senior staff in the National Church Institutions only adds up to a further nine people. There are no UKME/GMH Diocesan Secretaries (the most senior staff role in each diocese or Principals of Theological Educational Institutions) at all.

While the Catholic Church has increasingly turned to foreign clergy, the trend is not limited to one denomination. Dr. Israel Olofinjana sees himself as part of a growing wave of ‘missionary migrants’ – clergy who come not out of economic necessity but with a clear spiritual calling. “I didn’t come here as a refugee or asylum seeker,” he says. “I came as a missionary migrant to give something, not take.”

Olofinjana says that the migration of priests from Africa, Asia, and Latin America is not accidental, rather it reflects a broader shift in the global centre of Christianity. “Churches are growing in the Global South while they are shrinking in Europe,” he says. “So it’s inevitable that we now look to where the church is alive to help sustain it here.”

That help, however, is running thin. Within the Baptist Church alone, Olofinjana says that fewer people are getting into training for ministries each year compared to over 2,000 churches that need pastors. “Many of these churches don’t have anyone to lead them,” he says. “The shortage is not small , it’s a crisis.”

Archdeacon of Reigate, Daniel Kajumba says that young Anglicans from Africa and Asia who came to Britain do not feel welcome in Church of England churches. Therefore, many of them went to Pentecostal churches, where they felt “affirmed, accepted, welcomed, and nurtured”.

Owing to similar reasons, Dr.Olofinajan has been in favour of Pentecostalism and is also currently serving as a Baptist minister. In Baptist churches, there is no strict hierarchy like the Church of England but a flat structure and each church runs more independently than its Anglican counterparts. For clergy like him, the mission is spiritual, but also practical. “I preach from a place of transition,” he says, “because migration is part of my story and the Bible is full of stories like mine.”

Similarly, a strong will to follow God and the mission of filling in the shortage of priests in the UK and serving local parishes is what has kept Father Benny committed to doing his work. He believes that the young and immigrant priests are a bridge between older traditional generations of priests and a newer generation of catholic parishioners. “We are a little bit of relaxed people. We are not like, if you don’t go to church, you go to hell”, he says.

Father Chris says that he is positive about the role of foreign clergy and credits the energy that Father Benny brings to the Church. “ He attracts a group of enthusiastic young Indians, which we did not have before. He shows more enthusiasm than us older people”.

While Fr. Benny represents one stream of foreign clergy, others arrive through different paths, like Rev. Sungil Han. Originally from South Korea, Rev. Sungil disagrees with this thought by Fr. Benny and says that today’s churches in the UK have become similar to a social organization with a lot of humanism. “Teaching and the sermon from the ministers has become quite weak,” he says.

Rev. Sungil, much like Fr. Benny, felt a strong spiritual calling in his early adulthood while he was in the Korean Airforce. But unlike Fr. Benny, he chose to come to the UK following the advice of his mentor instead of getting ordained.

Sungil, now a minister in Exeter, faced a lot of difficulties when he first came to run a church in Birmingham more than a decade ago. Sustaining himself without income and having difficulty in speaking fluent English added to his woes of handling a church with diminishing members. “I think in my mind, I wanted to explore what the world lies,” says Rev. Sungil.

But things started to turn around when Sungil Han took the reins in his hands and helped restart the Korean congregation in Birmingham. To attract a larger audience, he changed the language of worship to English despite being not fluent with it. “A Korean student helped me translate for about one year then I started to preach in English”.

He says that there is a severe shortage of priests in the UK’s parishes and blames that on weak preaching and rising secularism. “One person looks after around five churches, we need more ministers”, says Rev. Sungil. He believes that there is a gradual decline in the church’s popularity over the last two decades because the church no longer presents a spiritually-distinct experience. “The younger generation maybe, would not feel very interested in church life because outside the church they can find more interesting things”.

But, Rev. Sungil is determined to revive the interest of British people in faith and he does so with his simple teachings. He says he likes to focus on basic, Bible-based worship rather than focusing more on entertainment like the modern churches. “Rather than doing activities, I tried to do just the basic settings. Naturally, they also want to come to listen or experience real life”, he says.

While priests like Benny and Sungil are stepping in, religious scholars warn that the problem runs much deeper than just filling in parish priests and ministers. Prof. Abby Day, an Emerita Professor of Race, Faith & Culture at the Goldsmiths University in London says that this decline is a result of generational changes. “There are tons of churches but people are not turning up. It’s a generational decline.”

To help others navigate the same path, Olofinjana now mentors incoming missionary clergy through a centre he co-founded. “I tell them, yes it will be hard, but don’t give up. We came here because we’re called and that calling doesn’t stop when it gets difficult.”