As weekly attendance at British churches is plummeting, can inclusive pastors, immigrant congregations and outreach efforts breathe life back into British Christianity?

Every Friday afternoon, Karl Stephens stations himself on Cardiff’s Queen Street with a stack of gospel tracts and a flask of hot chocolate. To passersby, it looks like an average evangelist stall. To Karl, it’s a lifeline for a faith he believes Britain is in danger of losing. For him and his team, this weekly ritual has been their way of keeping Christianity alive in a country where the churches are emptying faster than they can be filled.

For eight years now, Karl has stood on the same stretch of pavement, striking up conversations with passersby, offering prayers, or simply lending a listening ear. “We are under no particular church, the authority is the Bible,” he says. “We don’t preach, we just serve”.

By his count, he has distributed more than 40,000 tracts and connected around 5,000 people to local congregations. “We connect people to a church then it’s up to them to take action.”

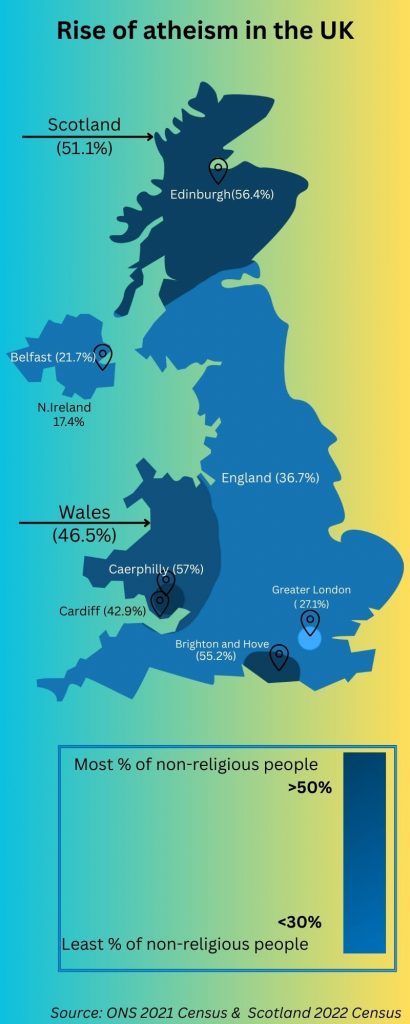

Karl’s efforts are significant in the country where Christianity is in slow but steady retreat. The 2021 census revealed that, for the first time in recorded history, Christians make up less than half of England and Wales’ population.

Churches are closing, congregations are aging, and clergy are in decreasing supply. For lifelong attendees like Karl, the question is not just where did everyone go, but can the church ever bring them back?

Religious scholars and sociologists argue that what we are seeing is not a sudden collapse but the result of a long cultural drift. “Religion has not been transmitted from generation to generation,” says Prof. Abby Day, an Emerita Professor of Race, Faith & Culture at the Goldsmiths University in London. “We’re three generations in decline now. You are not going to get a 12 year-old walking in[to the church] off the street if their parents, and their grandparents, never did.”

In the past, belief was inherited, often wrapped up in school assemblies, Sunday lunches and baptisms. Today, many of those rituals have vanished. About only 5% of the population now regularly attends Church in England. Prof. Abby Day says that the cultural importance of churches has eroded along with a sense of belonging they provide.

The problem, she says, is not that people are actively anti-religion. It is that they were never introduced to it in the first place. “You can’t revive what was never lived,” she says. “There’s no tradition left to pick back up.”

More than thirty years ago, Sundays in Cardiff carried a rhythm Karl Stephens could set his watch to. The clanging bells echoing through the streets, the rustle of hymn books, the murmur of greetings exchanged beneath high vaults with fragrance of incense. The church doors swung open to a tide of pensioners, schoolchildren and a community gathering not just in faith, but in habit and tradition.

Back then, the church was a sea of faces and voices, the air warm with choral harmonies and candlelight. Today, as Karl takes his usual seat near the front, the silence rings louder than any sermon. The echoes are longer and shadows deeper. While whole rows lie untouched, Karl realises it’s in that silence, not in statistics that the quiet decline of Christianity reveals itself.

“We had to pull out extra chairs at Easter. Now, we’re lucky if we fill half the pews,” says Karl looking around the empty congregation hall that he used to visit since his childhood.

While many churches in the UK are shutting down or are on the verge of closing, a surprising ray of hope is emerging among young British adults. Professor Philip Esler, a Biblical scholar from the University of Gloucestershire says that there is a recent rise in church attendance among young British men and that he is hopeful of the youth seeking meaning in their life.

“Young people are surprisingly open and this decline is not irreversible. It complicates secularisation theories”.

Social experts and economists have said that this rise in secularism can be attributed to advanced technology, education and access to modern world amenities. The age of consumerism fostered materialism. Materialism, at its core, is the belief that possessions bring happiness.

Prof. Esler says that people are now realising materialism and secularism to be unsatisfying.

One key reason materialism proves unsatisfying is hedonic adaptation, sometimes called the ‘hedonic treadmill.’ This psychological concept explains that humans quickly adapt to new possessions and experiences, returning to a baseline level of happiness.

“There’s a connection between personal happiness and mental health and getting sure to go to Church. You could have fewer hospital admissions for mental illness and help the country,” says Prof.Esler. He says that going to church can provide a sense of community, reduce isolation among young people and improve their mental health.

Prof. Andrew Davies, a scholar of theology and public religion at the University of Birmingham agrees with this thought of Prof.Esler and says that the UK’s growing mental health crisis is not purely medical but more of an existential one. In 2023, around 22% of young adults had a mental health difficulty, according to reports by NHS Digital.

Prof. Davies says that crises like climate change, anxiety, loneliness and post-pandemic instability have caused many young people to search for deeper answers. “Many young people are not hostile to religion, they are curious”.

“People are looking for peace and purpose, the mental health crisis emerges from not knowing why we are here”. He says that the decline of traditional sources of purpose like faith, family, and community are no longer working properly and has left many directionless. People are seeking structure and belonging in an increasingly individualistic society. “Christianity and churches can build a community-framework for everyone,” he says.

“One of the biggest areas where people are leaving the church is around inclusion and particularly on sexuality and gender,” says Prof. Andrew Davies. “If young people feel the church is homophobic or exclusionary, they won’t come back.”

He says that religion and particularly Churches should provide opportunity and equality to everyone without using it to restrict people. In the UK, the religious landscape regarding LGBTQ+ inclusion is diverse, with some churches maintaining traditional views and others evolving towards greater acceptance.

In this changing landscape and evolving Christianity, Reverend Dwayne Morgan is leading the Inclusive Community Church in Dorset. Rev. Morgan says that there is still an opposition from the traditional churches towards LGBT+ people in the ministries.

A study from Leeds and York confirms that churches licensed for same-sex weddings have experienced noticeable increases in attendance, often from LGBT+ individuals seeking spiritual belonging.

Rev.Morgan says that exclusionary stances, particularly on sexuality and gender, drive young people away. Often, he says, churches deceptively welcome LGBT+ people while secretly aiming to change them. “They are leading people deceptively. They’re saying you’re welcome, when in reality, they believe that they are not what they should be”.

Contrastingly, his Church mainly ministers to LGBT+ individuals by providing them with spiritual support which the traditional churches usually fail to do. “We overtly say that thank God for gay men, thank God for lesbians, and thank God for trans people”, says Rev. Morgan.

However, he agrees with Prof. Esler and Prof. Davies and says that he sees the decline of Christianity in this country as a cultural and generational phenomena driven by consumerism, distraction and going away from spiritual habits. “It’s so hard in society, I think, for people just to stop and reflect. Now they just keep going, and ignore the reality of life.” Rev.Morgan says that Christianity offers a connection to God and a better understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Inclusive Community Church engages in a variety of innovative outreach programmes in the form of a stall at the pride parades, arranging group meets of Space Youth Project at their church and by helping the members to relax and slow down their fast-paced lives. “Every person is reached differently by where they are in their lives. And the best we can do is try to be where they will find us,” says Rev. Morgan.

Rev. Morgan’s ministry shows one way forward by building communities of inclusion inside the church. But outside church walls, others are taking a very different route like Karl Stephens, an accountant turned evangelist continuing his outreach activities for Christianity in Cardiff, all due to strong personal calling.

For Karl, evangelism in today’s age is not about giving sermons about hell and judgement, it is about service, presence and conversation with the open-minded people. “It’s no longer that you are going to heaven or hell, now people are curious. That’s good,” he says.

He says that his efforts are necessary because the modern church has lost a sense of compassion and urgency while they are on a decline since the last two decades. “The church is asleep, there’s not much work being done”. Karl says that his approach may be humble and he does not see it as a campaign for numbers but as a living expression of faith.

While evangelists and inclusive pastors are building new paths, British churches are still struggling with identity and mission. “The native British population has secularised perhaps faster than I thought it would,” says Prof. Grace Davie, a sociologist of religion at the University of Exeter.

She says that it is not simply a drop in attendance, but a much deeper cultural loss. “We’ve lost the vocabulary, the capacity to speak well about religion in public life.”

Prof. Davie says that some of the gaps in churches have been filled by immigrant Christians from Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe who bring with vitality, tradition and conviction along with them.

During colonial rule, British missionaries introduced Christianity across large parts of Africa, the Caribbean, and South Asia. Generations later, many migrants from those former colonies like Nigeria, Ghana, Jamaica, India, and others have been bringing that same faith back to Britain. “They are here because we were there,” she says. “It’s a salutary lesson that perhaps other people have better answers than we did.”

While traditional churches and its congregation consisting primarily of white British population is dwindling, immigrant congregations are growing in the country and often thriving better than others. In cities like London, Manchester and Birmingham, black-majority and Pentecostal churches regularly fill with worshippers every Sunday. These churches give a sense of community to immigrant Christian populations offering not only spiritual support but also acting as food banks and language classes.

Prof. Davie says that some of the gaps in the Christian churches in Britain have been filled by people coming into this country. Many of these Christians come from countries where faith is still central to daily life. “Christians have come from Nigeria, Ghana, Zimbabwe, the Philippines, Brazil and they bring a theological conviction that feels at odds with the UK’s increasingly casual relationship with religion.”

She says that she is cautious about any revival but acknowledges that change is happening in terms of Christianity in the country, just not always in the ways the old Church expects. “You retain the identity, but you lose the content,” she says. “Faith today is often more cultural than committed, symbolic rather than spiritual.”

Yet for some, especially the young people, Christianity is starting to feel like a choice again instead of a burden or a duty, a rather countercultural way to make meaning.

Among all the data and debate, perhaps the future of British Christianity won’t be decided by institutions, but by individuals, people who choose to show up, reach out, and serve in ways that feel real. Whether it is a stall at Pride parade or a gospel tract on Queen Street, these acts are not grand solutions but they are quiet signs of perseverance.

The task is long, the culture is shifting, and the churches are changing. But for those like Karl Stephens, who keep showing up every Friday without fail, the mission is as alive as ever. “Was I successful? Yes. But is there more to do? Absolutely,” says Karl.