As the power of the Church declines in the post-colonial UK, why are the experienced missionaries cautiously hopeful of the future of mission work?

It was a grey Sunday morning in Britain, with light drizzle and church bells ringing into mostly empty streets. Yet inside a small parish in the Midlands, the pews were filled not with the usual religious elderly, but with young men, students, and immigrant families.

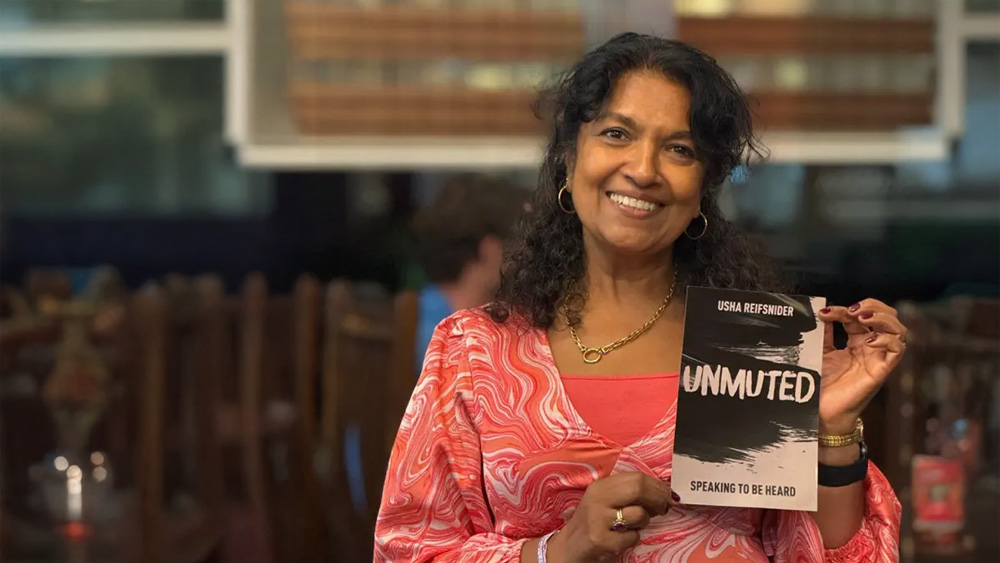

For missionaries Mark Newham and Usha Reifsnider, scenes like these are why they believe the future of mission work is far from over. After decades in their mission fields from Mongolia’s capital to Costa Rican villages, they see hints of a quiet revival.

“While many headlines paint a picture of inevitable decline, we see a more complex reality,” says Mark, who recently returned from three decades of work in Mongolia. Usha too says, “These communities are vibrant. They bring not just numbers but resilience and faith practices that the UK desperately needs.”

Their hope is not rooted in sweeping revival reports or booming statistics, but in the slow and patient work of building trust, sharing meals, and walking alongside people as they explore faith. For them, mission is no longer a one-way street from West to Third world countries, it is a global exchange of service and ideas.

It is a hope shaped not just from observing the present-day changes but also in years spent far from home. For Mark Newham, that journey began three decades ago, when his calling took him from the rolling hills of Devon to one of the remotest corners of the world.

It was the year 1993. The USSR had just split a couple of years earlier and one of its closest communist allies, Mongolia, was experiencing a transition to democracy. A young missionary from Britain stepped down from a plane in Ulaanbaatar, a cold city still wearing scars of communism.

Mark Newham had arrived with his wife for a mission in one of the remotest places of the world leaving behind his comfortable life in Devon, England. At a time when secularism was on the rise in public discourse about religion in the UK, they headed for a place which barely knew Christianity.

“We were just ordinary people,” says Mark. “We were not doctors or teachers, we just prayed, ‘God, find us somewhere to go’”. That prayer led to three decades of mission work by Mark in central Asia and parts of eastern Asia.

It all started in the mid-1980s when Mark moved to Devon and started working with his local church community to live by faith and prepare for missions to other parts of the world. He spent four years in communal living before getting clarity on the location where he would be serving.

At a Christian conference in 1992, Mark learned of the need for mission workers in Mongolia. He says, “We didn’t need supermen and women in Mongolia because we have a Superman in Jesus. What we needed was ordinary people to come and live.” Mark and his wife committed to serve in Mongolia with just a small support of £50 per month from his local church.

They started teaching vocational programmes like carpentry and plumbing along with Bible lessons for youth in Mongolia. Eventually, they realised they couldn’t just stay as foreigners on a tourist visa, so they registered a business to gain legal status and employ locals.

Having started a bakery and cafe there, Mark says that it was never about the profit but to provide jobs to locals and gaining their trust. “From day one we said, we’ll never cook the books, we’ll never do under-the-table deals, even if everyone else does. That made life harder, but it was part of our witness”.

During that period, it was very common amongst small business owners to manipulate their accounting books to evade high taxes especially in post-communist countries like Mongolia. But for Mark and his family, it was about living the gospel especially when unseen.

Within a few years, Mark joined a bigger missionary organisation based off US and Europe to expand the scope of his mission in Mongolia. “When Christianity entered Mongolia, it was a broken country. Christianity came in and gave them hope,” he says.

With greater support, Mark could guarantee wages to local workers regardless of profit. His work in Mongolia and later China formed part of a broader legacy stretching back two centuries, when Britain sent missionaries worldwide, especially to Africa and East Asia.

Missionary societies like the Church Mission Society and the London Missionary Society sent thousands abroad, training candidates in specialist colleges and sending them to Africa, Asia and the Pacific. This era saw missionaries as pioneers of both faith and empire, often backed by colonial structures that opened doors for the kingdom.

By the late 19th century, Britain had become a major global missionary base. Almost 2,000 ordained missionaries and laypersons totaling nearly 6,000 were serving overseas. The Church Missionary Society had sent more than 1500 men and women abroad by the end of the 19th century, training about a third of them in London. The London Missionary Society had dispatched nearly 1,800 missionaries by the mid-20th century.

By the mid-20th century, this dominance began to shift. Independence movements, the decline of the British Empire, and rising national churches in those countries changed the face of missions. British missionaries shifted from being the primary leaders to becoming partners or facilitators in local Christian movements.

At the same time, back home, the story was different. From the 1970s onward, church attendance in the UK steadily declined, and new ordinations started to fall. While Britain continued to send missionaries, about 15,000 as recently as 2010, the overall trend was downward.

This trend, which picked up pace in the 19th century saw a surge in youth-led missions from the 1960s in the form of Youth with a mission(YMWA) and Campus Crusade which reflected a new, more informal approach of sending ordinary Christians rather than exclusively clergy or professionals.

Mark’s mission in Mongolia showed how demanding the life of ordinary missionaries can be. Despite offering so much, Mark and his wife were subjected to hostility in their early days especially from Mongolian officials in the form of police interference in Bible lessons, tax threats and even some locals poisoning their dog.

Determination and patience won trust. “By the time we left, we had employed two of the police chief’s daughters, and he had become a good friend.” Mark says that this slow, relational approach is missing from the impersonal style of many large UK missions.

Mark adds that he emphasised helping locals to contextualize the faith instead of imposing western Christianity. “I used Paul Hiebert’s critical contextualization model and respected their traditional customs such as hair-cutting of children.” He says this approach encouraged local churches to reflect and adapt.

Paul Hiebert’s critical contextualization is a model that helps churches evaluate local cultural practices through scripture, deciding whether to keep, adapt, or reject them instead of blindly accepting or condemning them.

Religious critics have often criticised western Christian missionaries of supporting the colonial propaganda which more or less carried a saviour mindset.

Professor Philip Esler, a Biblical scholar from the University of Gloucestershire says, “White European men being kind of colonial agents is not a thought which I’m happy about.”

Mark says that missionaries should act as guests approaching local culture with humility. “You don’t go in telling people what they should believe. You go in and learn first, eat their food, sit in their homes, and only after they trust you, you explain why you’re there,” he says “If you go thinking, ‘I’m here to save you,’ then you’ve already got it wrong. We don’t save anyone, Jesus does. Our role is to live faithfully and let people see that.”

He says that future missions must not be top-down but deeply incarnational and trust-based.

After three decades on the Mongolian mission, building friendships and faith communities, Mark returned to a changed Britain. The church he had left was older, smaller, and short of clergy, with dioceses merging parishes. Once the centre of global evangelism, Britain was now in need of missionaries itself.

While Mark’s mission took him east into a post-communist Asian country, Usha Reifsnider’s journey took her across the Atlantic to Peru and Costa Rica and eventually back home to Britain, where she now champions migrant-led Christian communities.

Usha, having served in cross-cultural missions since 1988 is a director at the Centre of Missionaries from the Majority World. “Mission is no longer a one-way street,” says Usha “For centuries, Britain sent missionaries to Asia and Africa. Now, the flow has reversed”.

Often, academics writing about this subject conclude that it is only migratory factors, such as economic recession, inflation, political dictatorship and instability, that have brought people from the global south to Europe or North America.

For Usha, this reversal is not just a theory, it’s her life’s work. Through the ‘Centre of Missionaries from the Majority World’, she supports pastors from Africa, Asia, and Latin America who are planting churches in Britain. “These communities are vibrant,” she says. “They bring not just numbers but resilience and faith practices that the UK desperately needs.”

Usha, who was born to Gujarati Hindu parents in England’s industrial Black Country, says she never imagined she would one day become a missionary. Her first encounter with Christianity came through Sunday school and the local church, which, in those days, functioned as a lifeline in working-class neighborhoods.

“Christians did good things for people like taking care of the poor, feeding the needy,” she says. “I wanted to do kind things for people, and that drew me.”

Usha says that she believes a mission is about support, care and diversity.

“Whether it was visiting prisons, teaching English, or working in orphanages, the focus was always on service, not on numbers or conversions.”

She says that the British and American models of mission work were poor, condescending and built on hierarchy. “If Christianity was meant for the whole world, then interpretation of Christianity has to come from the whole world.” Usha says that Christianity must be decolonized and interpreted through global cultural lenses.

Having served as missionary since 1988, Usha says that she faced exclusion and racism from other missionaries in the group primarily due to her skin colour. “People who look like me are the ones you do mission to, not the ones who do mission. They couldn’t get past my skin color.”

However, this is not a unique case of racial discrimination within church leadership and programmes. A report by Racial Justice Commission of the Church of England in 2024 confirmed the existence of deep-seated inequities within Church structures. It also says that ethnic minorities within the Church were often stereotyped and expected to conform to certain behaviours. Usha says that she is hopeful of successful and profound missions, but only if the mission radically shifts toward justice and friendship.

How missionaries behave shapes the way people like Usha see mission, not as Western-led leadership, but as decolonised service and relationship. As Christianity shifts to the Global South, the UK is no longer just a sender but also a receiver of missionaries, from Africa, Asia, and Latin America with the influx of missionaries who embody this new model of humble, relation-building mission.

Usha says that the churches in the UK have always focused on material things over spiritual engagement. “The British church knows how to do Christianity downwards by giving money, medicine and education. But it doesn’t know how to look another person in the eye and have a spiritual conversation.”

Her mission, she says, is to spiritually educate people in the UK, Europe and beyond. “We don’t need to dangle a carrot and quickly swap it for a Bible. If you believe Christianity meets a spiritual need, speak about it honestly.”

For her group, mission is not charity with strings attached but about honesty and dismantling colonial legacies valuing integrity as core to the future of mission.

Usha says that in the UK, she has high hopes for missionaries from Africa and Asia, seeing their presence not as British decline but as global rebalancing. “When Koreans and Africans come here, they’re doing what the Bible asks. Christianity was never just European.” Across Britain, African, Asian and Latin American missionaries are already planting churches where traditional ones shrink.

Mark says that although Britain’s churches have struggled for decades, he sees fresh signs of life. “While many headlines paint a picture of inevitable decline, we see a more complex reality”. He says that he believes the Bible Society’s Quiet Revival survey, which reports rising attendance over the last five years, especially among young men.

Despite their criticisms of past models, both Mark and Usha are cautiously hopeful, seeing mission less in institutions and more in ordinary people and diverse communities. Their optimism comes not from numbers but from a slow, faithful presence that listens, adapts, and rebuilds trust.

Though their paths differ, both agree that mission means presence, not control and living among people, learning their language, and serving without expectation. Such humility, they believe, may shape the future of faith in Britain.