Do traditional media houses and independent podcasters approach true crime differently, and what can each learn from the other about ethics, storytelling, and innovation?

Adam is hunched over a laptop, stitching together his most recent true crime episode. No editor is looking over his shoulder, no rules about structure or tone. He has the option to narrate the story backwards, play a spooky soundtrack, or let a suspect’s voice take centre stage. His fans return because they appreciate the freedom and unpredictability of his work.

“I can experiment with format, storytelling, and interviews without being constrained by bureaucracy,” says Adam Llyod, who runs the UK True Crime podcast from his home studio. According to him, independence is what keeps the show fresh. “Without a commissioner or editor to answer to, I can test new approaches and take creative risks.”

The atmosphere is different just a few miles away, inside the glass-walled BBC studios. Before they air, scripts are combed through, facts are verified, and each clip is carefully examined. Although it slows things down, the BBC’s reputation serves as a shield.

Unorthodox concepts must be evaluated in light of editorial standards, and occasionally they fail the test. Yet those who work there say it is not always what outsiders imagine.

Ceri Jackson, producer of the BBC Wales true-crime series Shreds: Murder in the Dock, says the reality is far leaner than people assume. “We haven’t got what people might imagine. There isn’t a huge team behind you. It is just you. You’ve got some executive producers who will see your script, but it’s down to you,” says Ceri. “You’re the one who’s got the record, the one who makes phone calls, the one who does the research.”

All true crime podcasts may sound similar to the average listener, although the rules of the game are slightly varied behind the scenes. Innovation can feel like survival to independent creators. For traditional media houses, caution is the price of trust.

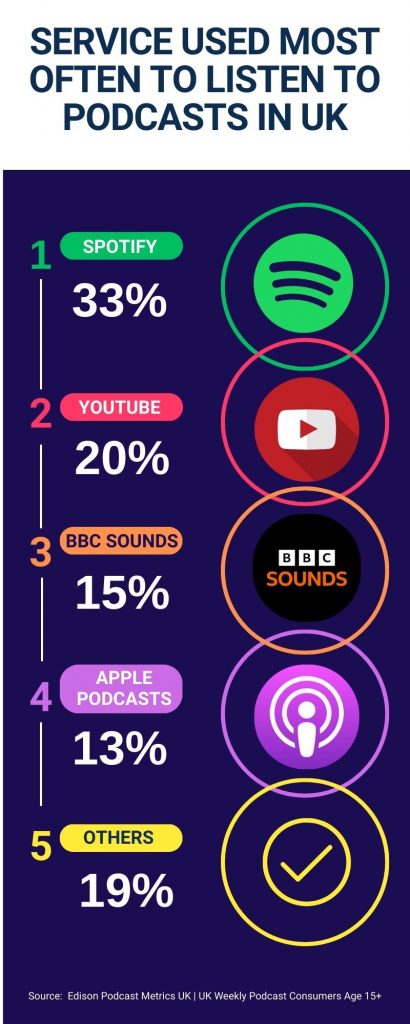

Podcasting in the UK is booming. According to new research, 51% of UK adults aged 16 and above listened to a podcast in the past month, and a third tuned in during the past week, both representing record levels of engagement. Weekly listeners tune in for an average of more than five hours, and they are paying attention, not just passing the time.

True crime has exploded in that craze. The genre attracts millions of listeners worldwide. According to statistics, Casefile: True Crime alone has 800 million downloads since its debut in 2016 and still receives between 7.2 and 11 million listens each month. Redhanded, which has won the British Podcast Awards’ Listeners’ Choice three times in a row, is one of the most popular podcasts in the UK.

According to industry insiders, audience connection is more important than lurid stories in this surge. Fans of true crime spend approximately seven hours a week watching their favourite shows, while fans of other genres only spend six hours. They champion it, rather than just consume it. More than 70% embrace branded or sponsored content, and 86% say they would listen to podcasts that friends recommend.

The surge of creators has been fuelled by the influx of listeners. The UK true-crime charts are now dominated by independent producers, many of whom operate from home studios. The Times’ Cocaine Inc. garnered over 750,000 downloads in just two months, putting it on track to reach one million.

According to PressGazette, UK true-crime charts are now dominated by independent producers, many of whom operate from home studios. However, the freedom to create does not come without a price; many brands continue to handle true-crime content with caution, fearing negative associations or backlash.

Driven more by passion than production budgets, many of the most popular shows in the UK are made in kitchens, bedrooms, or co-working spaces that are rented. Their creative freedom compensates for their lack of scale.

For many independent podcasters, technology has been a game-changer. Adam says, “Technology now allows me to produce professional-quality content independently at minimal cost. Independent creators brought innovation to true crime podcasting, making it more diverse and accessible.”

However, the dangers are constant. Independent creators bear the burden alone, without the support of editors or a legal team. A factual error or a badly chosen plot point may lead to criticism or, worse, legal issues. Then there’s the financial reality, which includes spending a lot of money on equipment, editing audio late at night, and constantly trying to grow your following.

To Mark Randelll, co-host of the Seeing Red Podcast, the balance they navigate is delicate. “Podcasting is unregulated, unlike radio or TV. We focus on victim-centred, factual storytelling and sometimes take creative license with structure, while maintaining respect,” says Mark. “True crime can reopen wounds, but can also bring closure. We stick to public records, avoid unnecessary intrusion, and consider the potential benefits for families.”

Sally and John from Investigators UK echo this hands-on, careful approach. Both have long careers in policing and law. Sally served in the police and later as a prosecutor, while John was in the police.

With decades of experience in policing and law, they approach each case with a level of expertise and authority few indie creators can match. “We started podcasting about four years ago as a hobby rather than a business,” says Sally. “Our approach is different from most podcasters. We conduct in-person interviews rather than relying on scripts, which gives the stories a more immediate and authentic feel.”

Despite the independence these self-sustained creators have, the BBC’s size and resources paint a very different picture in the same industry. It appears to be a powerhouse from the outside: slick studios, elite journalists, and the weight of a well-known brand point to a podcasting machine that is far more capable than anything an independent producer could accomplish.

It is not a magic carpet ride. You might be operating under the BBC, but you’re on your own.

says Ceri

However, the inside reality is frequently more stripped-down. Ceri says, “It is not a magic carpet ride. You might be operating under the BBC, but you’re on your own.”

Ceri says the journey of Shreds began with the 30th anniversary of the Lynette White murder and the flawed investigation that followed. She felt the story needed a more in-depth, immersive treatment after writing a lengthy long-read for the BBC website, so she pitched it as a podcast.

Ceri had to persuade the BBC to support the ambitious idea, and she only got a small amount of support. She says, “I had to really push to get agreement on it and got a very, very small budget to do it. So got a voice recorder. I obviously had access to the archive from the BBC, but that was it. It was just like, here we go.”

That mix of independence and accountability is a defining feature of BBC podcasting. The guidelines are a safeguard, protecting stories from sensationalism and ensuring accuracy.

Ethics and sensitivity were central to Ceri’s approach. She treated interviewees and victims’ families with care and respect. “You have a huge responsibility, and you have to care about the people that you’re writing about. They’re extremely vulnerable, you have to make sure you portray them in a responsible way, in a genuine way,” says Ceri.

True crime isn’t just about crime, it’s about people, about what’s going wrong, and about the aftermath.

The podcast was entirely victim-focused. “The ultimate victim was Lynette White…they were dragged for something that they never should have been even mentioned in relation to. If you can’t be ethical and empathetic, then you shouldn’t work in this realm. True crime isn’t just about crime, it’s about people, about what’s going wrong, and about the aftermath.”

Seeing the case as entertainment should not be the approach. Ceri says, “It should never be entertainment. Engagement, yes, but not entertainment. There’s always a fascination with danger, but true crime can and should be educational. It can highlight corruption, complicity, and societal failures. Done responsibly, it’s far more than entertainment.”

Despite operating independently, Sally and John of Investigators UK take ethical and legal responsibility as seriously as any traditional media outlet. Sally says, “We adhere to strict ethical and legal guidelines. We already operate carefully, ensuring respect, accuracy, and consent. We don’t deliberately cause issues. Everything we do is self-imposed and based on respect and authenticity. I would hate to think we’ve caused anyone problems or said anything incorrect. That’s never our intention.”

The approach they use demonstrates the trend of independent creators balancing creative freedom with accountability by prioritising victim-centred storytelling and strict standards, even in the absence of the BBC’s institutional framework.

The difference, according to Sally, lies in the time and pressure that traditional media staff are under. She says, “We have time and independence. We don’t rush to meet deadlines or sensationalise stories. Commercial media must perform and make money, which can affect accuracy. We focus on factual integrity and thorough investigation. We often uncover inaccuracies in books or media reports that others rely on as fact.

On the contrary, training and editorial guidance are what set the traditional media-produced shows apart. Ceri says, “The BBC has great training, and the editorial standards are high, but again, it’s down to you to adhere to those standards. You’re tutored in the editorial guidelines, which were like the Bible of the BBC. They’re robust, but they’re a guide, not a formula. There’s an awful lot of responsibility that falls onto the journalist. You have to meet those standards, and in many ways, it can be more difficult.”

Ceri treated interviewees and victims’ families with care and respect. She says, “You have to treat people as if they were members of your own family. If you gain trust with the people you’re working with, it should come naturally. You have a huge responsibility to care about the people you’re writing about. They’re extremely vulnerable, and even if they’re willing to participate, you have to portray them responsibly and genuinely.”

Even without the institutional framework, Sally and John take similar strides towards respect and accuracy. John says, “We build rapport over several calls before asking someone to be recorded, which usually results in cooperation. Most people are happy to participate because of the respectful, professional approach we take. We never pursue individuals who clearly want privacy, and we only publish verifiable facts.”

Their professional background helps build trust with sources. Sally says, “Being ex-police and a lawyer helps build trust. People know we understand procedures and context, so they’re more willing to share information. Our approach is professional, respectful, and informed, which opens doors that others may struggle with.”

Despite the differences in resources, structure, and editorial oversight, both BBC producers and independent podcasters are constantly learning from each other. The BBC benefits from the fresh, experimental approaches that indie creators bring, from unconventional storytelling formats to creative pacing and engagement strategies.

As Ceri says, whether you have a huge budget or just a laptop and a microphone, quality content is defined by curiosity, care, and commitment. Independent and traditional creators encourage one another to raise the bar for storytelling, research, and ethics.

In the end, this cross-pollination is what makes the true crime podcast landscape flourish. Independent producers contribute experimentation, imaginative risk-taking, and new viewpoints, while the BBC provides structure, training, and credibility.

“Independent creators brought innovation to true crime podcasting, making it more diverse and accessible,” says Adam. Both sides are working together to raise the standard by fusing ethical responsibility, creative storytelling, and thorough research to engage audiences in fresh and significant ways.