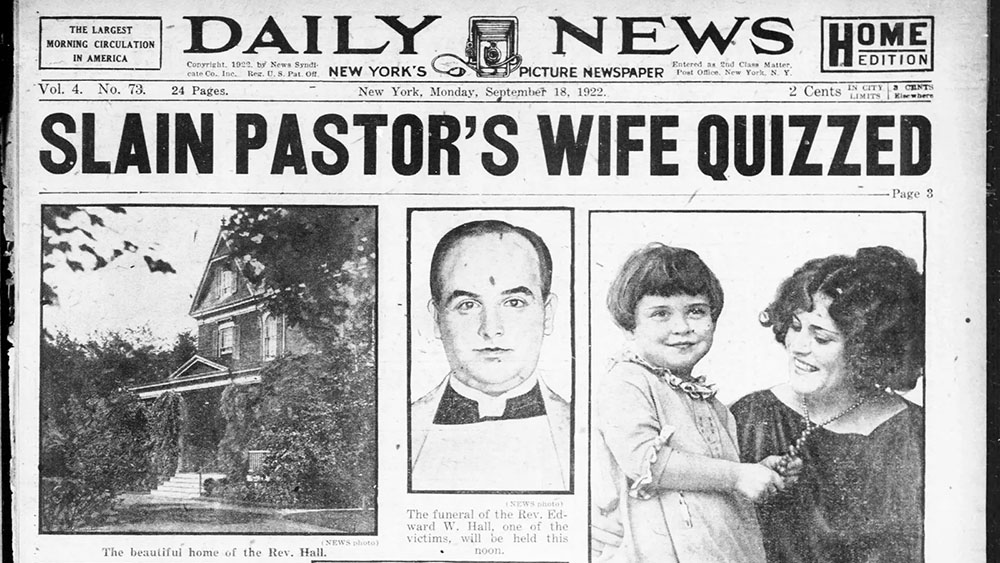

True crime podcasts attract millions, but with no shared rules, they walk a fine line between pursuing justice and exploiting pain. Should this booming genre develop its own code of ethics?

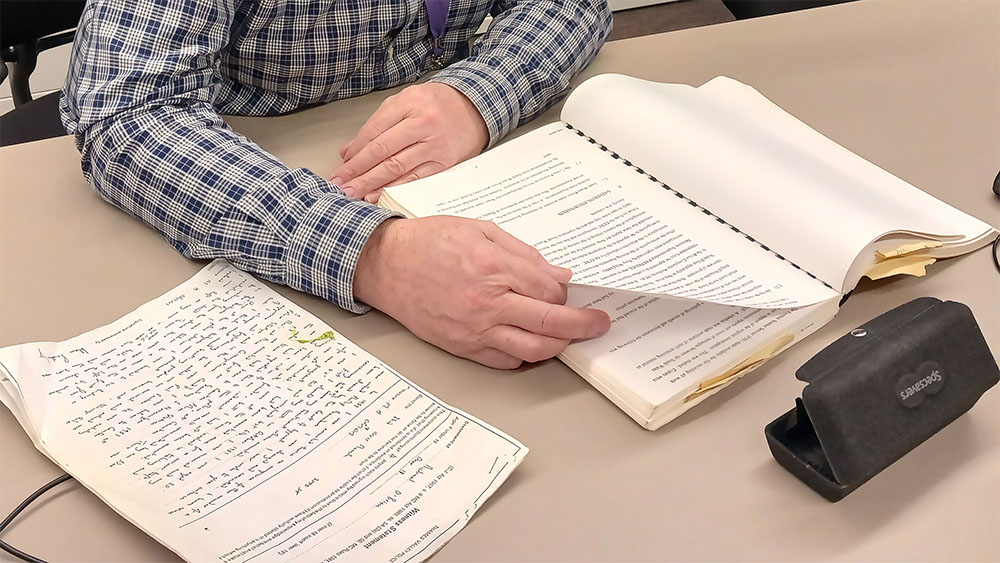

Mark’s eyes were narrowed, jaw set, fingers twitching. Pages scattered across the desk detail scenes of dread, blood, and death. At a glance, it would be easy to mistake him for someone orchestrating something dark. A figure in control of every detail.

But Mark was not the one behind the tragedy, he was the one telling its story. A seven-year-old child, found dead in his own home, lost to neglect. Tonight, Mark must decide: name the family or not? Include the harsh details, or hold back? Could he speculate about who to blame? The line between justice and spectacle is thin. He says full control of the story means full responsibility.

“I’m conscious that we are making money off other people’s misfortune. We have adverts and sponsorship in the middle of an episode,” says Mark Randell, 42, co-host of Seeing Red alongside Bethan Trueman, 35, acknowledging the rewards that come with telling these stories. “We make money off the podcast we have. A level of profile comes from it, so people know us. There are benefits that come with that.”

True crime is no longer a niche corner of the podcast world, it is its beating heart. In the UK, nearly 7 million people listen to true crime podcasts each month, making it the country’s second-most-popular podcast genre, just behind sport. An astonishing 30% of monthly podcast listeners tune in specifically to true crime. The appetite seems endless, and so the storytellers keep coming.

This boom is remarkable because of its breadth. Some shows are recorded at kitchen tables with a single microphone and a host, while others are produced in professional studios with teams of researchers. Some podcasters are criminologists or former journalists, while others are fans of true crime who just hit “record.” They are a part of an industry that now has live tours, sponsorship deals, and occasionally television adaptations, regardless of their production scale.

That range of voices includes projects that began in the most ordinary circumstances. In 2021, Phoebe Broad and Philip Drinkwater, a father-daughter duo, launched their own true crime podcast, Dad and Daughter Do Death, during lockdown as a way of staying in contact. Phoebe says, “It gave us something to do together when we were 130 miles apart. Rather than just chatting on the phone, we told each other true crime stories.” What started as regular conversations between them quickly developed into a show with a steady audience.

According to Philip, the podcast started out as a way to talk more frequently rather than as a polished output. However, choices about how to present cases became more important as the audience grew. Many independent podcasters are now in that situation, transitioning from informal discussions to material that reaches thousands or even millions of listeners.

Although the scale is immense, the framework is essentially nonexistent. There is no official regulation of podcasters, and there are no common guidelines regarding sensitivity, accuracy, or consent. The extent to which violence is described, whether names should be mentioned, and how theories are presented are all up to the individual hosts.

That freedom is thrilling to some. It is a burden for others. The absence of boundaries often puts the affected families in an exposed position where they never wanted to be, especially when their tragedies are recounted to millions of people.

As more people listen to true crime podcasts, the issue of accountability is inevitable. Victims’ families frequently complain that they are not consulted before their stories are told to thousands of listeners. Some people talk about only learning about episodes involving their loved ones after they have been released.

When Netflix released its dramatisation of the Jeffrey Dahmer case, Eric Perry, a cousin of victim Errol Lindsey, expressed his outrage at it. Even though he was talking about television, families whose tragedies are rehashed in podcasts share the same discomfort. In a tweet, Eric says, “It’s all public record, so they don’t have to notify (or pay) anyone. My family found out when everyone else did… My cousins wake up every few months with a bunch of calls and messages, and they know there’s another Dahmer show. It’s cruel.”

For some families, each new episode can reopen old wounds. The repeated retelling of a tragedy, even in a different format, can be emotionally exhausting and painful. “I’m not telling anyone what to watch. I know true crime media is huge right now, but if you’re actually curious about the victims, my family are pissed about this show. It’s retraumatizing over and over again, and for what? How many movies/shows/podcasts do we need?” says Eric in the tweet as reported by The Cosmopolitan.

This anger and frustration are not unique to high-profile cases. Lilly Dancyger’s cousin Sabina was raped and murdered when she was 20. Lily says, “Nobody has tried to make entertainment out of Sabina’s story, but if they did, I would burn their podcast studio to the ground.”

Lilly described their own loss and the intense reaction they would feel if someone attempted to turn their loved one’s story into entertainment on CrimeReads. She says, “I would do whatever I had to do to get them to give up on the project. It would be intolerable to me, physically intolerable like the way a body can’t tolerate rotten oysters, for someone to splash Sabina’s last moments and the horror of her death onto a TV screen, or to narrate it between advertisements for Casper mattresses.”

Podcasters themselves are aware of the weight of these stories. Sally Midgley, who co-hosts the True Crime Investigators UK podcast with her husband John, says, “We are very aware that we’re talking about people’s lives and sometimes deaths. We’re talking about people’s loved ones. Something that may have happened 30 or 40 years ago. But the people that we’re talking about and talking to remember it like it was yesterday, because it was such a big event.”

Making decisions about how to present cases is rarely simple, even with such understanding. Hosts have to decide whether to name the people involved, how much graphic detail to include, and how much to speculate when details are lacking. Every decision has the potential to have an impact on the narrative as well as the individuals it affects.

“We try not to be dramatic in our storytelling unnecessarily; we focus on the facts. But it’s hard. You want to be creative as a writer and a host; I want to be dramatic,” says Mark, co-host of Seeing Red, about the ongoing tension between creativity and responsibility. “I want to put the audience right there, as a fly on the wall while that murder is happening, and I want to describe it in graphic detail, but I have to try and pull away from that.”

There is no assurance that hosts’ decisions will please viewers or families, even if they adhere to rigorous research procedures and moral intuition. Publishing is a moral and professional challenge because every episode has the potential to cause backlash, misunderstandings, or unintended harm.

Podcasters’ decisions are influenced by their audience as well as by ethics. A combination of curiosity, empathy, and the “safe danger” of learning about violent crimes from the relative comfort of one’s own home often captivates true crime listeners. Many people talk about spending hours binge-listening because of story twists and cliffhangers.

For podcasters, that engagement is both motivating and pressing. They say the audience increasingly expects stories to be handled responsibly, with attention to the victims’ experiences, not just the crime.

Adam Lloyd, host of the UK True Crime Podcast, says this approach guides his work. He says, “It is about always being victim-centric. I think it’s just showing basic decency and not shaming them. Even if I don’t work to a strict ethical guideline, I will work to the standards of my audience.”

Listeners share a similar concern. Clare Evans, an avid true crime fan, says, “The way these stories are told, people remember the criminals. Ted Bundy, Steven Avery, Jeffrey Dahmer, we all know their names, but how many know the people who were the victims? I think that is unfair.”

The habits of listeners also put pressure on them. Reactions are amplified on social media, where messages, reviews, and comments appear nearly instantly after an episode airs. Due to the lack of an intermediary team to filter or mediate feedback, podcasters frequently bear the brunt of these responses personally. Every creative choice is immediately examined due to the direct connection and intense interest.

The audience’s emphasis on victims gives hosts a sense of direction and serves as a reminder of why they share these stories. Hosts frequently talk about their duty to educate, to highlight underreported cases, or to share the experiences of victims with a larger audience. However, that same reach can also lead to conflict: are artists fulfilling the demand for drama, suspense, and entertainment, or are they upholding justice? Every episode tests the line, which is rarely obvious.

Experts are calling for systemic change to govern ethical true crime storytelling, going beyond podcasters and listeners. Leading the charge to create a new code of practice for journalistic crime content is Dr Bethany Usher, a senior lecturer in journalism at Newcastle University and a former crime reporter. This initiative aims to provide a clear framework for ethical production across various platforms, including podcasts, documentaries, and police communications.

Dr. Usher emphasises the need for ethical standards in a piece by Newcastle University.

“Crime is media’s longest sustained genre, but there has never been a code-of-practice that defined the public interest and what ethical content is newsgathering, produced and promoted that specifically addresses its production and its unique place in society.”

says Dr Usher

Her project is developed with input from victims, producers, and audiences. It seeks to ensure that true crime content is produced with respect and responsibility. Dr. Usher says, “‘With each advancement in media technology, journalistic crime content has expanded, often but not always in response to popularity and profit. Now its capacity to attract clicks, shares and likes makes this a pressing concern when we consider the impact it can have on victims, their families and their communities.”

The proposed code contains guidelines that put victims’ and their families’ privacy and dignity first in an effort to stop exploitation and re-traumatisation. When the code is complete, it will include a “kitemark” to assist viewers in recognising content that has been produced ethically and to motivate platforms to support it.

Dr. Usher’s work highlights the growing recognition within the industry of the need for ethical standards in true crime content creation. She says, “So far there’s been a lot of positive feedback from industry, fan communities and victims who also feel that it is time for ethical change.”

Her efforts are part of a broader movement to balance compelling storytelling with respect for those affected by crime. She says, “The important thing for all of those who’ve agreed to take part in this project is that we keep in mind that this genre of media can have devastating impacts on real people when they are at their most vulnerable. For us, getting the ethics right is a matter of social justice for all of those that might have been let down in the past and for those who could be in the future.”

That tension between responsibility and storytelling is something podcasters themselves confront every day. “Some stories are sensational just in the telling of it, you know, some stories you just can’t make up,” says John, the co-host of True Crime Investigators UK. “But we just stick to the facts that are in the public domain, or those that people have told us.”

For others, the answer lies in remembering the person at the centre of the story. Mark and Bethan’s podcast often closes by focusing on legacies left behind, from charities founded by families to campaigns that raise awareness and drive change.

Mark says, “I see our podcast as a way of keeping the victim’s memory alive, and remembering the great things about their life and not necessarily the end of their life, which generally will have ended in brutal circumstances.”