A nationwide investigation reveals that nearly 90 percent of sanitary pads in China are shorter than advertised. How are Chinese women suffering from substandard products, and what does it reveal about health, consumer rights, and gender equality?

“I started posting mostly because I was desperate and frustrated,” says Xinyi Li, whose wellness blog now reaches over 50,000 followers. The 33-year-old sits in her apartment in northwest China, surrounded by stacks of sanitary pads she has tested over the years. “I’ve dealt with recurring vaginitis for almost a decade, and I realized so many women around me had similar struggles, but we were all suffering silently.”

For nearly ten years, Li endured a painful cycle. Every month during her period, boils would appear near her vulva. Doctors prescribed washes, suppositories, and medications. She would recover, only for the agony to return with her next cycle. “I tried everything else. But the pattern never changed. I’d get better, then once my period came, it all came back.”

It was only after years of trial and error that Li began connecting this to sanitary pads. “They’re just not breathable. Even the big brands. Sofy, Whisper, Kotex, none of them worked for me,” she says. The realization that the very products marketed to protect women’s health were potentially harming it hit her hard.

After she shared her experience online, she discovered she was far from alone. Thousands of women recounted similar struggles, many pointing to the same products. Among those who reached out was Xiaoyan Zhu, a college student in Beijing who is an active member in Li’s online discussion group.

Zhu recalls that both she and her mother were diagnosed with vaginitis three years ago. Despite repeated hospital visits and treatments that ranged from prescribed ointments to traditional medicine and even herbal saunas, nothing worked. “We tried everything doctors suggested, but honestly, none of it worked. My mom even heard from a neighbor that sauna could help. We tried too, but every time my period came, the symptoms returned,” Zhu says.

What struck her most was the silence around the issue. Doctors attributed their condition to lifestyle and stress, rarely mentioning hygiene products. Friends were difficult to confide in, since vaginitis was often associated with sexual behavior, which carries stigma. “And it is quite awkward to tell my friends about this, because people will generally relate this to chaotic sexual life. I couldn’t talk to anyone except my mom,” Zhu says.

Her suspicion about sanitary pads grew when she noticed her symptoms always occurred during menstruation. She and her mother used the same product, Sofy’s long night pads. Around that time, online communities were buzzing with posts suggesting that pads themselves were to blame. In late 2024, Chinese women discovered that their trusted sanitary pad brands had been deceiving them. What began as individual complaints on social media platforms exploded into a national controversy quickly dubbed the “Sanitary Pad Crisis.”

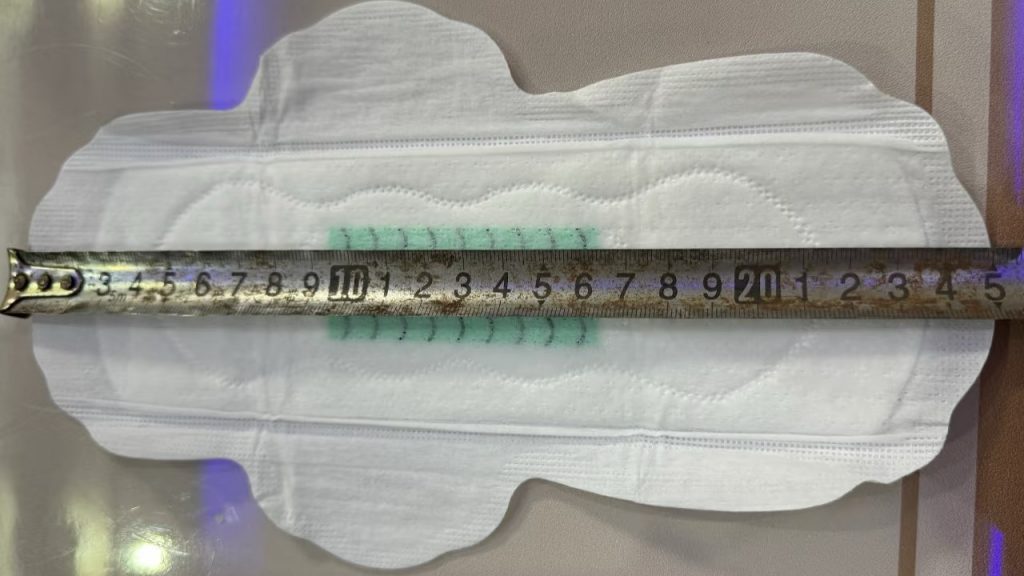

The scandal erupted when women across China began measuring their sanitary pads, only to discover a shocking truth: nearly every major brand was selling products significantly shorter than advertised. When The Paper, a state-backed news outlet, tested 24 different brands, they found 21 were at least a centimeter shorter than promised. While this fell within China’s four percent margin of error, the consistency was striking.

The deception ran deeper than just length. The absorbent core, the most crucial part of any sanitary pad, was even more dramatically reduced. In one case, a pad advertised as 28.4 centimeters contained absorbent material measuring only 22.6 centimeters. That is a 20 percent difference. Women were not only getting less product but also less protection where they needed it most.

Dr Dongfang Xiang, director of gynecology at Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine, warned in an interview with Chinanews about the risks. During menstruation, women’s immune resistance is naturally lower, making them vulnerable to infections from contaminated products. Poor-quality pads can trigger vaginal inflammation, cervical problems, and even pelvic inflammatory disease, which may lead to infertility, miscarriage, or premature birth.

Harmful chemicals made the problem worse. Pads were found to contain harsh bleaching agents and fluorescent substances that could cause skin allergies, ongoing itching, or even raise cancer risk over time. For women like Li and Zhu, who had dealt with repeated infections for years, these discoveries were infuriating.

“My underwear was breathable, my hygiene was good, but the pad? That’s the only thing that trapped heat and moisture down there,” Li says. She could not believe that products designed to maintain hygiene may have been causing the very problems they promised to prevent.

Social media amplified the scandal at a dizzying pace. On Weibo, the hashtag “Sanitary Pad Scandal” racked up more than 170 million views within weeks. Women posted photos of their own measurements, and what they found was disturbing. Reports emerged of foreign objects like needles and insect eggs discovered inside pads. Images circulated of products containing what appeared to be black cotton, possibly recycled and contaminated materials harboring dangerous bacteria. Some women conducted pH tests at home and discovered their sanitary pads had acidity levels similar to curtains or tablecloths.

In response to the controversy, the founder of ABC, one of the major brands, issued a public apology. In a video statement, he said, “I will not make any excuses and sincerely apologize once again.” He also promised that the company aimed to have no differences from the national standards. It was the first company to directly address public concerns, but by then the entire industry had endured what insiders called “the darkest 48 days” in its history.

Chinese officials also responded, acknowledging the public feedback and confirming that new regulations and national standards were under review. “As for whether to adopt these suggestions and how to adopt them, we have already proposed a revision plan and will implement revisions as soon as possible. This process will take some time,” a government department stated.

China’s sanitary pad standards, last updated in 2019, allow significant deviations in product specifications. The four percent tolerance might seem minor, but when applied across the industry, it amounts to systematic shortchanging of consumers.

Industry insiders suggested manufacturers were not making mistakes but exploiting the rules. Tests showed products from the same factory varied by as little as two millimeters, suggesting precise control. The economic implications are immense. China’s sanitary pad market serves hundreds of millions of women and generates billions in annual revenue. “Low costs and high demand,” one blogger from Jilin said, describing the sector’s appeal.

Pan Wang, an associate professor at the University of New South Wales, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, “The public outcry about sanitary pads shows growing social concerns about women’s health and consumer rights in China. It has cultivated a sense of sisterhood and unity among women consumers.”

The crisis has indeed sparked wider debates about gender equality and women’s treatment in Chinese society. Many who had endured problems silently began speaking out. Social media became a platform for collective action, with women supporting each other’s complaints and exchanging recommendations.

In response, sales of medical pads increased as women began using them as alternatives. Some turned to international or premium brands, willing to spend more for reassurance. Others looked into reusable options, though some studies have raised worries about toxic forever chemicals in certain eco-friendly products.

Zhu and other group members felt a sense of recognition. “We started trying other products, but there was no big difference. Finally, we decided to make pads ourselves using special toilet tissue for pregnant women. It was thinner, lighter, and more breathable. Then I shared this idea with other victims online,” she says.

Some women even began launching their own brands. Many documented the entire process on social media to attract customers, often presenting their projects as feminist ventures. Some pledged to hire only women, claiming to offer authentic female-made products. But controversies soon followed. One such company was revealed to be operated by a man.

Li is cautious about trying new brands and questions the marketing emphasis on “female-only” teams. “After that big consumer rights expose, everyone was like why are men making pads? They don’t even get periods. But here’s the thing, just because women make the pads doesn’t automatically make them better. Unless they’re actually innovating with better materials or designs, it’s the same product with a pink label.” She believes that genuine product quality and innovation matter more than gender-based marketing strategies.

Zhu is also skeptical about new brands launched by young female entrepreneurs hoping to profit from the crisis. Once Zhu questioned one of them, she was disappointed. “I’ve become really cautious about this stuff. I pointed out that the factory she was partnering with was the same one that had been producing some of those substandard products we’d heard about. But instead of addressing my concerns, she just blocked me,” she says.

The crisis escalated on March 15, the International Day for Protecting Customers’ Rights. China Central Television reported that a company in Henan Province was buying defective items and scraps from major manufacturers, repackaging baby diapers and sanitary pads, and selling them for high profits. These illegal traders bribed employees of legitimate companies to obtain defective sanitary pads and diapers that were meant to be destroyed, purchasing them at extremely low prices. Half of these waste products were repackaged and resold in rural stores or marketed online as unbranded bulk packages, selling 100 pieces for just over one pound.

Period poverty remains a serious problem in China. The market for these off-brand sanitary products is far larger than most people realize. Research shows that well-known sanitary pad brands make up only 40 percent of the market. That means 60 percent are unbranded products. Many women are forced to use potentially dangerous recycled pads simply because they cannot afford regular ones, which remain expensive due to high tax rates.

Unlike the first disclosure, officials took action immediately. The Henan company was shut down and its representatives were punished. The government also announced that new national standards for sanitary pads would be introduced in July. These included stricter limits on bacteria and fungi, a ban on using discarded or previously used sanitary materials in production, and a prohibition on fluorescent chemicals that could migrate onto the body. But there was no change to the concerns most often raised by consumers, such as pH levels and the actual length of pads.

For the substandard products already on shelves, there was little enforcement to recall them or fine the companies. Unlike the United Kingdom, where the Consumer Protection Act requires companies to recall unsafe products immediately, China has limited legal mechanisms to enforce recalls. Many vendors simply discounted older products or bundled them with promotions before the new regulations came into effect.

As outrage cools, change may still come. Manufacturers now face heightened scrutiny from empowered consumers who measure products and post results online. New brands promise transparency and higher standards, aiming to rebuild trust.

However, for many women, trust has already collapsed. Zhu says: “But one thing I am sure about is I won’t buy any products anymore. I felt unsecure using pads displayed on the shelf. They are expensive and uncomfortable, I would rather make them on our own.”