From tainted formula to the sanitary pad scandal, Chinese consumer confidence is shaken again. As women voice anger and industry defends itself, can trust be rebuilt at home and abroad?

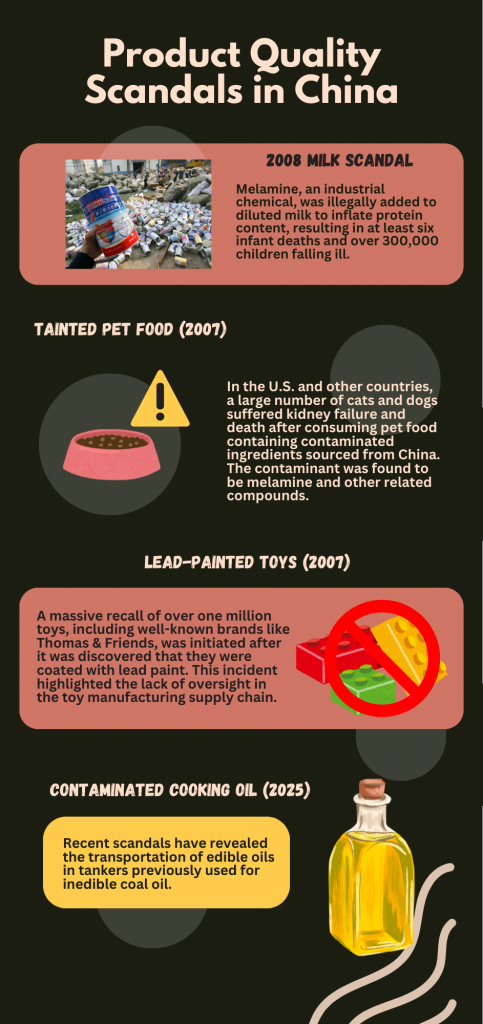

When thousands of babies fell ill in 2008 after consuming milk powder tainted with melamine, the Sanlu scandal became one of China’s most infamous food safety crises. Six infants died, and hundreds of thousands were affected. Parents stopped buying domestic formula, turning instead to imported brands.

Seventeen years on, Chinese consumers are again questioning the safety of everyday essentials. This time, it is sanitary pads. Investigations have revealed that nearly 70% of domestic brands were shorter than advertised, and some were accused of containing potentially harmful substances. For many women, the discovery felt like a profound betrayal.

“Women spend at least 10,000 yuan over their lives on something so basic,” one furious Weibo post read. “If this essential can’t even be safe and reliable, what else can we trust? How can our health be guaranteed?”

The outrage spread rapidly online. At the heart of the debate was not only product quality but also the fragile relationship between Chinese consumers and the companies that serve them. For many, the pad controversy is less about centimeters of shrinkage or lab test results and more about a fundamental collapse of confidence in “Made in China.”

Not everyone in the industry agrees it deserves the label of a scandal. “People are making a big deal out of length issues, but let me explain what’s really happening,” says Jun Lin, founder of Calmfident, a young sanitary brand targeting Asian consumers. “The backing material is plastic with elasticity. During production, it gets stretched. When you cut it to 245 millimeters, it might shrink back a tiny bit due to temperature, which is completely normal.”

Chinese regulations on sanitary pads have long specified minimum length requirements. That standard itself has not changed. But in recent years, leading companies such as ABC promised “zero negative deviation,” pledging to manufacture pads that are slightly longer than required so that any shrinkage during production would not affect the final product. By raising the bar, major brands effectively reset consumer expectations, and when smaller or newer players failed to match them, it looked to customers like cutting corners.

After the wave of online exposes, disappointment with domestic products grew so widespread that consumers began turning to foreign alternatives. On social media, women swapped recommendations for Japanese or Korean pads, and even began buying them through daigou (informal cross-border purchasing agents ) who source overseas goods. Yet the question remained: are foreign pads really superior?

“Not much difference, honestly,” says Lin. “Europe and the US test for one additional thing that China doesn’t require for sanitary pads. But not having the requirement doesn’t mean we don’t meet it. We’ve tested our products and they pass.”

The comparison highlights a regulatory gap. In the UK and EU, sanitary products must comply with chemical safety directives that explicitly test for phthalates and volatile organic compounds, substances linked to reproductive health risks. China’s GB/T 8939 standard, last updated in 2008, covers absorption, leakage and material quality but does not mention phthalates. That difference has become a talking point in online debates, even as many manufacturers privately note that their products already comply with international benchmarks.

In Lin’s view, Chinese sanitary pads are in fact highly competitive. “I personally think Chinese sanitary pads are really good, maybe even better than most of the world’s, because Chinese consumers are the most demanding globally,” she explains. “Seriously, in China you have to ship pads in proper boxes because if the box gets even slightly dented, people return them. In Singapore, they just throw pads in a plastic mailer bag and nobody complains.”

The real issue, she argues, is not production capability but fragile trust. “I think people’s emotions about this issue have gone beyond the actual quality problems. It’s become about broader trust in Chinese products. But the reality is, Chinese manufacturing in this industry is actually quite advanced, with good supply chains and strict quality control. The problem is more about communication and trust than actual product quality.”

That collapse of confidence has, paradoxically, opened space for new brands. After years of dominance by multinational giants like Procter & Gamble and domestic leaders such as ABC, smaller companies are seizing the moment. One of the most visible is Mianmian de Yang (Fluffy Sheep), founded by social media influencers Zhao Zihan and Yuan Yang. Their signature “Moonlight Box” which has 50 pads for 29.9 yuan—went viral in livestream sales. Within a year of launching, monthly revenue topped 10 million yuan.

Their appeal goes beyond low prices. Zhao and Yuan are a lesbian couple, raising an adopted child together. In China, where homosexuality exists in a legal grey zone. Neither criminalized nor formally recognized, such openness is still rare. The couple’s personal story and unapologetically feminist branding resonated with a younger generation of women who want products made by women, for women. In a market long dominated by male-led corporations, Fluffy Sheep’s positioning was magnetic.

The strategy worked. By late 2024, the brand’s TikTok account had more followers than those of established giants like Sofy and Always. Its livestreams routinely sold out within seconds. “Buying pads has become like trying to get Taylor Swift tickets,” one user joked online. According to analytics firm Feigua, Fluffy Sheep’s flagship “Moonlight Box” brought in over 50 million yuan in monthly sales, accounting for more than 60 percent of its revenue.

But not everyone is convinced. Industry veterans point out that smaller companies often lack the technical expertise and research capacity needed for long-term success. “Some brands promote themselves as ‘all-female teams,’ but that’s not really possible in this industry,” Lin notes. “The people who really understand sanitary pad technology are mostly men because this is a traditional industry. The technicians who change materials, adjust machines, do electrical work—they’re mostly men, and they’re more experienced. When these brands run into technical problems, guess who they ask for help? A man. So why the obsession with all-female teams?”

The backlash came swiftly. In April, reports emerged that consumers had found foreign objects including red spots, black specks, and yellow stains in Fluffy Sheep pads. The hashtag “Fluffy Sheep sanitary napkins exposed” shot to the top of Weibo’s trending list. The brand tried to respond by posting videos of Zhao visiting factories and declaring, “No matter the cost, we put safety first.” But the controversy dented its image.

The timing made the scandal even more explosive. Just as the pad story dominated online discussions, a nationwide food safety uproar broke out over allegations that state-owned Sinograin and private conglomerate Hopefull Grain and Oil Group had been transporting both fuel and cooking oil in the same tankers without cleaning them between loads. For many, the juxtaposition was chilling.

“I don’t think this is a coincidence that the sanitary pads were discussed at the same time as the oil scandal,” Lin says. “This is premeditated. The pads thing was covering for a bigger news to mislead people.”

The edible oil scandal, implicating some of the country’s largest state-linked companies, was described in Beijing News as an “open secret” in the transport industry. The State Council quickly announced an interdepartmental investigation, but the revelations showed the sense that safety lapses are systemic and accountability weak.

In one recorded incident, a tanker transported coal-derived fuel from Ningxia in western China to the port city of Qinhuangdao in Hebei, covering more than 800 miles. Instead of returning empty or being cleaned, it immediately loaded nearly 32 tons of soyabean oil for delivery, without any sanitation in between.

State media including CCTV and People’s Daily roundly condemned the practice, calling it “tantamount to poisoning” and an “extreme disregard for consumers’ lives and health”

Experts highlighted serious health risks. Shaowei Liu, a food safety expert cited by CCTV, explained that residual fuel contamination can lead to acute poisoning symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and may cause long-term organ damage to the liver and kidneys.

Public outrage quickly spread across social media. Posts featuring the hashtag #edibleoil gained millions of views as people demanded stronger oversight and accountability

Visitors to a logistics app called Shipping Help which once allowed users to track tankers across the country found the service disabled amid the scandal. The developers claimed it was due to “an upgrade,” prompting widespread speculation that the shutdown was an attempt to suppress citizen tracking of contaminated oil shipments.

Chinese law explicitly prohibits transporting food alongside toxic or harmful substances. The national Food Safety Law states that food “must not be stored or transported together with toxic or harmful items,” and mixing such materials, especially non-edible substances with food is a criminal offense potentially punishable by death in severe cases.

The State Council announced a high-level investigation and pledged that violators would be “severely punished.” But for many Chinese, the damage was already done. Cooking oil, unlike baby formula or sanitary pads, is an unavoidable staple.

By contrast, the official response to the sanitary pad complaints was muted. Local health bureaus confirmed they were investigating but offered no timetable. National regulators have not tightened standards on chemical residues or pad length. State media has acknowledged consumer anger but stopped short of pressing companies for accountability. For many women, the silence was just as troubling as the scandal itself.

It was a pattern they had seen before. After the 2008 milk crisis, officials were criticized for withholding information, forcing parents to share their own test results online. Now women are doing the same with pads, posting lab reports, comparing foreign and domestic brands, and crowdsourcing safety advice.

The consequences stretch beyond China’s borders. In 2008, countries around the world restricted imports of Chinese dairy products. Sanitary pads may be less likely to face formal bans, but reputational damage is harder to contain. If Chinese consumers themselves reject local brands for essentials, why should international buyers trust them?

Some entrepreneurs are already looking abroad for validation. Lin registered her company in Singapore, both to reach overseas markets and to signal credibility. Others emphasize premium positioning selling “medical grade” pads at much higher prices to reassure anxious buyers. But these strategies are only stopgaps.

What emerges is a cycle, scandal erupts, official response lags, consumers retreat to foreign products, and entrepreneurs scramble to restore credibility. From infant formula to sanitary pads, the label “Made in China” no longer carries the same assurance it once did.

Whether that trust can ever be rebuilt remains an open question. For now, millions of Chinese women face a dilemma every month that between costly imports, new domestic challengers, and a nagging fear that even the most intimate necessities might not be safe.

“I won’t buy any pads from the shelves anymore. I don’t feel secure using them. They are expensive, uncomfortable, and untrustworthy. I’d rather make them on my own.” says a Beijing university student who has suffered repeated vaginal infections.