Assignments, lectures, even healthcare now depend on a stable connection. What happens when students are forced to wait, reload and fall behind?

In a small house in Yorkshire, a family of five shared just one laptop for months. The 12-year-old daughter had to wait until late at night to do her homework because her elder sister needed the computer for her GCSE studies.

Life became much easier when a charity gave them a second laptop. Suddenly, the younger daughter could start her homework right after school instead of waiting for hours. The family stress went down, and their mother’s English skills also began to improve with better access to online resources.

This story, reported by The Guardian, shows a problem that many British families face but few people talk about. Across the UK, many students and families are facing a digital struggle that goes beyond just missing devices. John Butcher, Emeritus Professor of Inclusive Teaching in Higher Education at The Open University, has witnessed the extent of these struggles firsthand.

“Some of our students attempt to complete their whole undergraduate course just on their mobile phone, because that’s what they had, which is obviously very difficult. And I think some of them, even if they had laptops, struggled perhaps to pay for the broadband requirements that they might need to access the virtual learning environment and some of the materials on there,” he says.

The physical challenge of mobile learning goes beyond mere inconvenience. “It’s really hard because they often have to work in Word and they lose formatting and they can’t use spell-check as easily,” Professor Butcher says. Hours can disappear on tasks that should take minutes, such as trying to format a reference on a small screen or reading a long paper that was never designed for a phone. Students end up fighting tools instead of using them.

Even with a laptop, study can stall when the internet is unstable or shared. Jacqueline Baxter, Professor of Public Leadership and Management at The Open University, remembers the challenge during the pandemic. “We saw how serious the issues of digital poverty were,” she says. “We had teachers who were having to go deliver data dongles (portable internet devices) to families who didn’t have a computer and couldn’t afford data.”

Digital literacy and digital poverty are just exacerbating the inequalities that already exist between the rich and the poor.

– Prof. Baxter

For many households there was one computer for everyone, and only a limited amount of data. People topped up at newsagents because home broadband was too expensive. Every month became a choice between the cost of data and other basic needs.

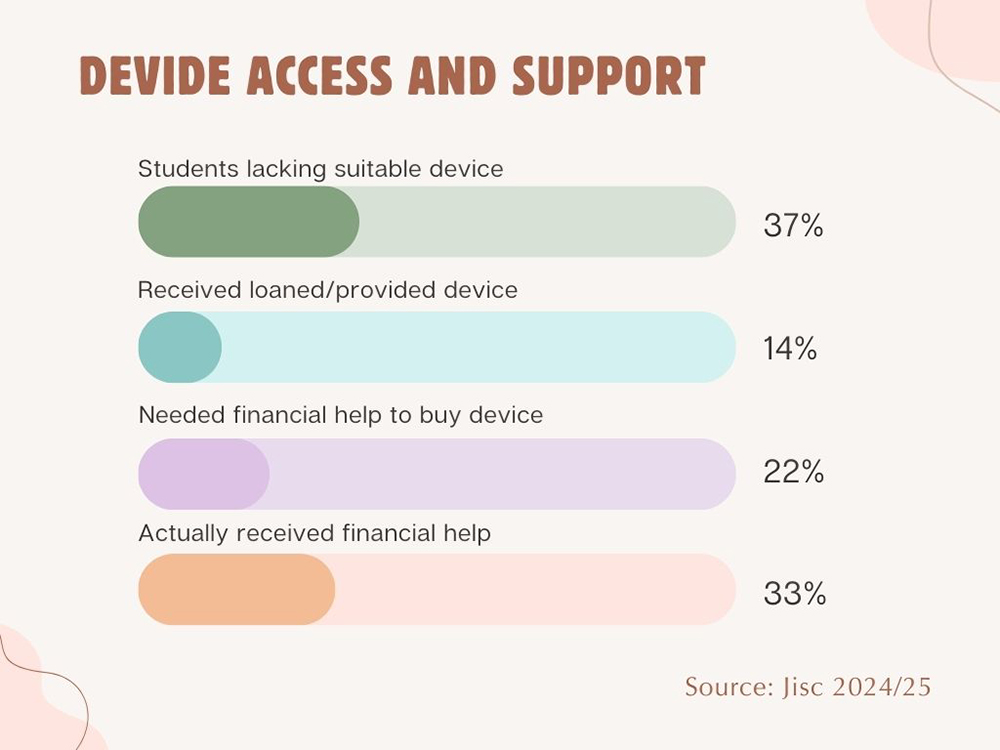

Recent research from the Minimum Digital Living Standard project says that more than 4 in 10 UK households with children fall below a basic digital benchmark for modern life. That means many children still lack simple things many others take for granted. A working device. A stable connection. Enough data to join a class or upload an assignment.

The financial barriers Professor Butcher observes among his mature students illustrate why this digital divide persists. “Many of them are hesitant about taking out a student loan, even though they can, because they worry about going into debt,” he says. “Adult learners are often financially responsible for their families. They have children and other things they have to prioritize rather than pay out for decent equipment.”

Yet money is only part of the problem. Even when The Open University offered IT bursaries specifically to help with equipment costs, Professor Butcher noticed that reluctance remained. “There was still something of a reluctance,” he says. “Many adult learners were not particularly digitally aware, which made them quite anxious about studying online.”

Assumptions make it worse. Professor Butcher has heard his colleagues say, “Everybody’s got a smartphone now.” He pushes back. In his experience, not everybody does, and even when they do, some cannot afford to use it well or do not feel confident with it.

Such assumptions also hide a bigger problem that Professor Baxter finds particularly troubling. “We assume that students are digital natives, but the kind of software that we use and the way we expect students to behave in study is very different to the way they might behave on TikTok or Instagram or other social media platforms,” she says.

“Although they may be well aware of how to use Twitter, they’re not always very good at using the kind of software they have to use to create illustrations online or write essays,” Professor Baxter says. “Because we’re open access. That means we don’t require A-level qualifications, because of that, a lot of our students haven’t had the opportunity to engage with academic technology beyond their phones or social media. So it can be a little bit of a shock to some of them.”

For some learners, the fear becomes part of study. Professor Butcher has watched students worry about the most basic actions online. “People worry about pressing the button to send an assignment in, which is going to disappear and be lost forever,” he says.

The language on IT help pages can add to the problem. “Some of the barriers are technical,” Professor Butcher says. “They can’t get their laptop through a firewall, or can’t load the required software. And the IT support area that they might produce to help students are written by technical experts, so students find the language very unhelpful.”

The fear runs deeper for mature learners. “The more mature a learner is, often the less willing they are to ask for help because they feel they ought to know,” Professor Butcher says. They see younger students apparently navigating systems with ease and then feel ashamed of their own struggles. “They don’t really feel that they belong in university. They’ve made a big step to take that first step, and they feel they should know how to do this stuff.”

All these lead to clear results in the classroom. If students cannot reliably access or use the university’s online materials, they are far less likely to complete assessments and pass their modules.

“A lot of the material is now available only online, so they wouldn’t really be able to study properly. We have a lot of kind of induction material online and we found that the students who regularly looked at that were very likely to complete and pass their module and those who wouldn’t face a high risk of failure. So there’s something about digital engagement as well,” says Professor Butcher.

But it’s not always a matter of motivation. For some students, narrow living spaces simply don’t leave room for a quiet desk. “Even people that had computers or tablets didn’t have any private space to study, and they couldn’t go to the library during the pandemic. But for middle class people who come from fairly affluent families, they just take it for granted,” says Professor Baxter.

The decline in public resources has only made matters worse. “Maybe 10, 20 years ago, it was very easy for an adult learner to go into the local library and use the broadband there and possibly use a laptop there as well,” Professor Butcher says. “But because of austerity, lots of public libraries have closed or reduced opening hours, so the availability of that kind of free public IT is diminishing.”

Since 2016, according to The Guardian, hundreds of council-run libraries have either closed or been handed to volunteers, and many more have cut hours. Closures have hit the most deprived areas hardest. When the nearest open branch is miles away and shuts early, “just use the library Wi-Fi” is no longer an answer.

Beyond the decline of physical libraries, students are now expected to use online libraries as a basic part of their studies. That skill forms a central part of digital literacy. “Digital literacy in terms of studying means the ability to use online library and things like that, so access books that are actually e-book form and access papers that are in e-book form,” says Professor Baxter.

“It also means that you can work your way around the Internet, that you can determine, for example, what is likely to be the truth and what is likely to be fake news, and that’s one of the things that we try to teach our students: not to believe everything they read on the Internet, because some sources appear to be very credible but they’re not,” says Professor Baxter.

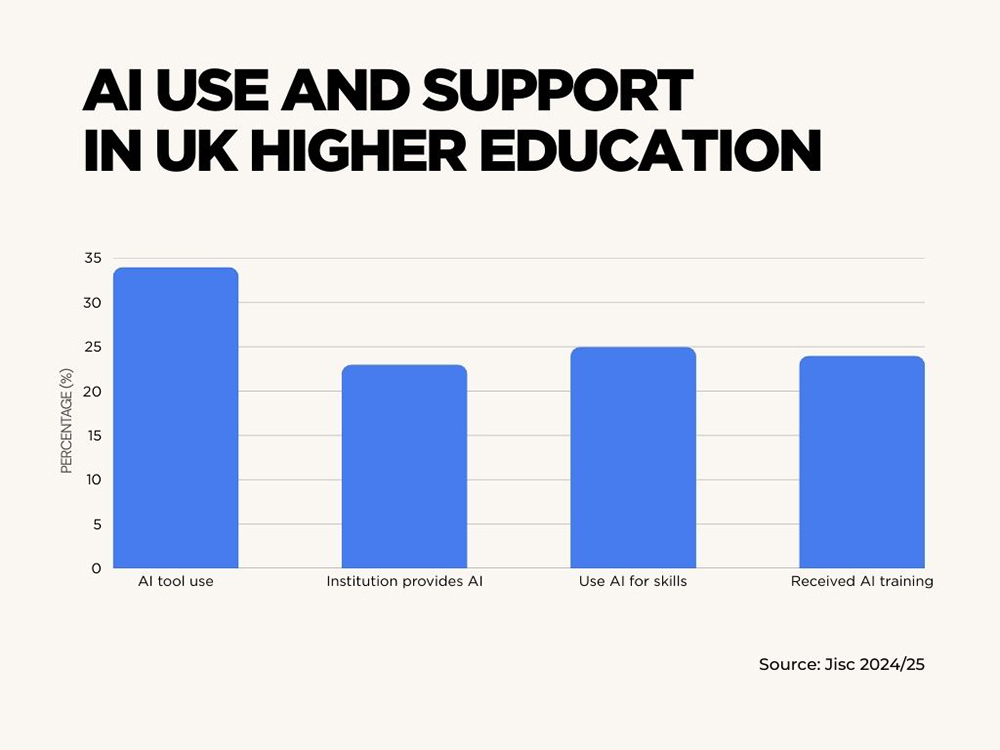

Just as universities begin to address these divides, artificial intelligence has created new forms of exclusion. Professor Baxter sees digital literacy now extending to understanding AI. “It’s about determining when the answers the program gives you are likely to be correct and where they’re likely to be incorrect,” she explains. “There’s also the bias in terms of AI. It’s very biased towards white westerners, because a lot of the GPT programs are designed in the States, and they’re designed by men. So there’s actually built-in prejudice.”

For students already struggling with basic digital skills, this adds another layer of complexity. “A lot of students, particularly in the first year at university, will say, ‘oh, I’m going to write this essay with ChatGPT,’ and of course it turns out it’s not in their words, it’s a load of rubbish, and it draws on sources that simply aren’t credible,” Professor Baxter says.

This isn’t just an Open University problem. She sees it across the sector in her role as external examiner at other institutions. “How do we enable our students to use artificial intelligence in a constructive way and yet still do proper learning on their courses?” she asks. “It’s a big issue for all universities now.”

Addressing these challenges, however, doesn’t always require advanced technology. Sometimes, institutions can make meaningful changes simply by thinking more carefully about their students’ experiences. Professor Butcher recalls a successful intervention at The Open University that demonstrated this principle.

When a tutor left a bequest specifically for widening participation, the university used it to create IT bursaries. “We made it available to students, in a sense, once they had submitted their first assessment on paper,” he explains. “After that, the whole experience was online. Any students who had submitted it on paper were offered the opportunity to have a few hundred quid to spend on a laptop.”

The results were transformative. “The vast majority of them were absolutely delighted to use it and said that’s the only way they kept going,” Professor Butcher says. “They were really worried about the cost.”

– Prof. Butcher

If you can’t access a website, if you’re worried about having the money to get your broadband going, the easiest thing, frankly, is to give up.

He believes that universities should be more proactive in offering support, especially to students who are anxious about spending extra money. Many institutions do have bursary schemes, but they are often difficult to access.

“You have to apply, you have to fit in complex paperwork, you have to produce lots of evidence, and frankly that’s quite off-putting,” he says. “Some of our students told us in our research that it was a nightmare trying to get financial support.”

Professor Butcher also advocates for peer support systems that can bridge the confidence gap. “Successful students from disadvantaged backgrounds could be used to mentor and support new learners to kind of demonstrate it is possible,” he says. “They’re very powerful role models. Often students from disadvantaged backgrounds feel they’re struggling on their own, and actually they’re not.”

The urgency of closing this digital divide extends far beyond education. Digital exclusion now means social exclusion in ways that would have been unimaginable just two decades ago. As Professor Baxter says, “It affects every area of our lives now. It affects studying, it affects health, it affects finances.” She points to a telling example, “Our GP now does not accept appointments if you ring up, you have to actually go over the Internet to book.”

Such changes go beyond simple inconvenience. When essential services move online without alternative access routes, digital poverty becomes a barrier to healthcare, employment, and civic participation.

Professor Baxter frames this as a question of basic rights. “Digital literacy and digital poverty are just exacerbating the inequalities that already exist between the rich and the poor,” she says. “Essentially creating an underclass who doesn’t have access to good signal, who doesn’t have access to the data they need to get better qualified, to get better jobs.”

She believes this is not only about technology, but about fairness. “The world is very, very unequal,” she says. “Inequality is rising and it’s very much part of most societies now, unfortunately.” To her, improving digital access is part of a bigger goal, “To create equality, really.”

Achieving that goal requires action on many levels. Individual institutions must design support systems with genuine empathy for disadvantaged students’ experiences. But solving this problem also needs long-term support from policymakers. “It needs to be addressed not just locally or by organisations that can help. It needs to be addressed by government on an international scale,” says Professor Baxter.

The cost of inaction grows daily. “If you can’t access a website, if you’re worried about having the money to get your broadband going, the easiest thing, frankly, is to give up,” Professor Butcher says. “So I think the universities lose a few possibly talented students that way, which is a great shame.”