2 out of every 3 people who currently migrate from rural Spain are female. But for those who stay, what is life in small villages like for them?

Paola Biota is one of approximately 6 million women in rural Spain. A rural Spain which is at a crossroads in its chances of future survival due to recent trends of depopulation.

As reported in national newspaper El País, between 2010 and 2017 62% of all small villages and towns saw their populations decrease.

In a survey produced as research for my project on “Empty Spain”, I asked 100 people what they thought were the main challenges for rural Spain.

None of the challenges explicitly mentioned the sometimes harsh situation for women, despite the historic – and in some cases ongoing – masculine domination of rural villages in population, employment and mindset.

Yet, in the ongoing battle to save these historic villages, the increasingly prominent role that women are now playing is vital.

Paola Biota is one of these women and lives in one of these villages.

Valareña

Valareña is a rural village like many in Spain.

It has a population of around 150, a shop, main square and bakery, its pharmacy and doctor’s surgery are open for just three hours a day and though there are three bars, only one of them remains open.

Located in Aragón, an autonomous community which is situated in the north-east of Spain, bordering France, it’s continued existence owes much to its residential women.

Paola shares the frustrations of many in rural Spain.

“It hurts a lot that we are always forgotten… and it’s annoying that they take away rights, services and access little by little so that the village disappears,” she says.

“They treat us as uncultured, but they forget something that’s really important: our values and culture in other aspects of life,” she adds.

Despite rural depopulation, villagers like Paola are keen to address stereotypes which, even in the 21st century, seem commonplace.

“In my friendship group we all have our studies; some of them degrees, others in college and others decide to stay and work in agriculture and breeding animals. There is a diversity, but absolutely none of us are uncultured,” she says

“Of course, there are many elderly people who did not have the opportunity to study, but they are not uncultured. I can assure you that they have incredible knowledge about life, working in the fields, nature, animals, collectively, solidarity etc,” she adds.

And Paola points to the role women play in her village in order to keep it alive.

“Many times we talk about it, if it was not for the women our village would already be dead,” she adds.

Indeed, 11 of the 12 who make up the town’s Festivals Committee are female and although women currently make up less than a third of rural Spain’s population, this small village demonstrates how they are contributing more and more to all aspects of rural life.

“In Valareña, our cultural activities are mainly organised by women. Men do get involved with some activities but to a less extent. In the end, it is the women who organise everything and have more motivation in taking the village forward,” Paola explains.

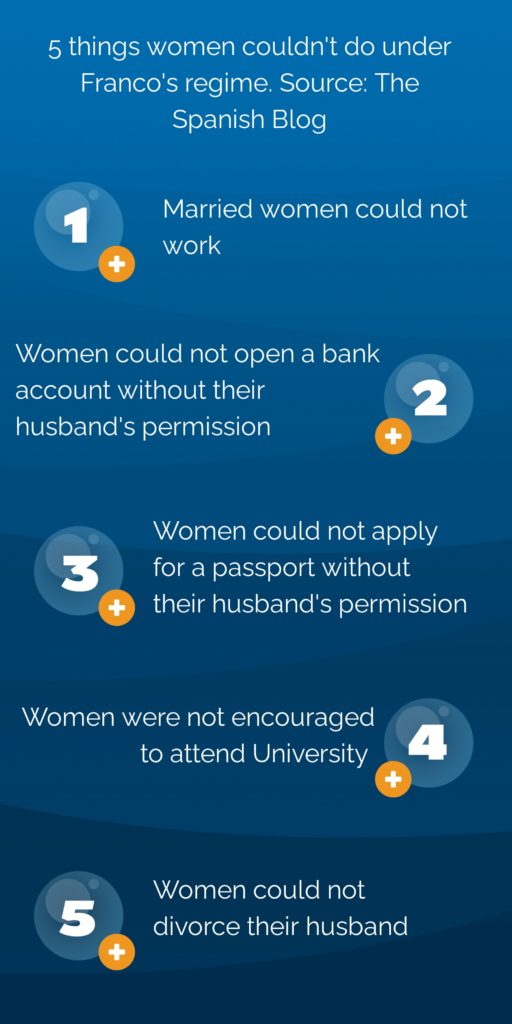

Over the last few decades, especially since the fall of the Francoist dictatorship in 1975, women indeed have been liberated and are now able to play a more prominent role in their villages.

Women fighting back

“The situation has improved a lot over the last few years, because before rural women were practically invisible. They never received anything for their hard work. That was, simply, exploitation,” Juana Borrego Izquierdo, the president of FEMUR (The Federation of Rural Women), explained to Plataforma Voluntariado.

“Those of us who live in villages have to fight against depopulation, against the ageing of our population, against the exodos of young people who leave because they can’t find work and against a low-birth rate. But we also have to fight, everyday, against something even stronger: machismo,” she added.

Indeed, despite the increasingly influential role that women play in villages like Valareña, Paola Biota admits that being female in rural Spain is still far from easy.

“One of the biggest challenges we face is how to reconcile a working life with having a family, especially given that our village does not have nurseries to look after and entertain children,” she says.

Although investment in such public services is vital, Paola also argues that the eradication of gender inequality will only come about through a change of mentality.

“We have definitely improved as a society but, for example, we still hear sexist comments when we are in our local bar or walking down the street,” she explains.

“Despite this ongoing behaviour, we are very proud to be rural aragonese women and we are trying to change things. Little by little machismo is being eroded,” she adds.

Rural discrimination

Last year, an article published in El Diario Rural, a newspaper for rural villages across Spain, claimed that rural women face at least 6 different types of discrimination based on their gender.

One of the main challenges for women is “rural masculinization”, coined by Professor Rosario Sampedro from the University of Valladolid.

Put simply, this concept argues that most jobs in rural Spain are still typically seen as “masculine”, leading women to migrate from smaller rural villages to larger towns or urban cities in search for employment.

In fact, according to RTVE, the Spanish national broadcaster, 2 out of every 3 people who swap village life for urban cities are female.

Indeed, the regional newspaper Diario de Valladolid in 2018 described its territory as tending to be both older and masculine, with nearly 90% of its villages, towns and cities counting more males than females amongst its population.

Women’s organisations

Despite female depopulation, provincial organisations such as ISMUR – The Social Initiative of Rural Women – in Segovia, Castilla y León, are working hard to defend, hand in hand, rural and female interests.

ISMUR organises workshops and resources for women, migrants and the elderly in order to improve the quality of life of those who tend to be, in their view, excluded from society.

“We have changed attitudes and ways of seeing women, who are now participating in decision making and in the organs of power of our agrarian organisations, cooperatives and administrations,” says Montserrat Arranz Cárdaba, its vice president.

“Ideas about feminism have changed and now it is understood as a journey of justice and equality,“ she adds.

But this journey of justice and equality has, for decades, left women seemingly play second fiddle to their male counterparts, at least in terms of legal and economic rights.

The co-ownership law

“We are in a rural world where its economy, riches and development are in agriculture and cattle; where the property and land should be for who works with it. If a women has always participated in this, with their hard work and dedication, and it depends on her, how can she not be an owner with her rights and obligations? Finally, women can be co-owners,” says Montserrat.

Montserrat is refereeing to the co-ownership law which was passed in 2011 by the Spanish government, enabling women to become co-owners of agrarian land for the very first time, one of the historical stumbling blocks to gender equality in rural Spain.

However, nearly a decade on, bureaucratic problems and obstacles for women who tried to put this law into practice means that it has not yet heralded the new age of female agrarian owners that is was meant to.

“After years asking for co-ownership the government pass a law which has hardly been disseminated and is not very attractive,” she argues.

As of 2019, across the country, women were co-owners of just 503 plots of agrarian land, as reported in Agro Información.

Whilst Castilla y León and Aragón had 23 and 158 plots registered respectively, many autonomous communities have struggled even further to make this law effective, nine years after its promulgation.

This was the case with Madrid and the Balearic Islands who had not a single piece of land registered under the co-ownership law, whereas seven out of the remaining 15 autonomous communities, including Catalonia, the Canary Islands and Andalusia, count upon five or less plots of land registered under the law.

Juana Borrega Izquierdo, in her interview with Plataforma Voluntariado, was not however critical of the law per se.

“With the co-ownership law (which favours real equality, backed in legal and economic terms) many women are now able to have better lives. This allows them to have access to social security and a pension. It also gives them certain protections against separation or divorces. Women can now have a sort of deposit, and, above all, recognition for their hard work. This is very important.”

However, she did argue that a change in mindset is needed on part of the women whose lives this law was supposed to change for the better.

“Notwithstanding this, there are still many women who do not know about the programme or dare to register for it. There is still a lot of fear in what being an independent woman means,” she said.

Historic role of rural women

Despite the ongoing barriers, members of ISMUR such as Montserrat are also keen to emphasise that women have always played an important role in rural Spain, whether they had legal and economic rights such as the co-ownership law or not.

“Women in rural Spain have always been fighters, workers, women who want the best for their children (just as much as in the cities) but with additional difficulties, because to be a women and live in a village makes it doubly difficult because of the lack of basic services (nurseries, day centres); mobility; lower income; the necessity to contribute to the family economy; difficulties in the world of work; and especially because of culture, the traditions which make us feel guilty for what we do or stop doing,” she says.

“We have helped write the villages’ history, and without saying anything have worked hard like lionesses, brought up its children and all without rights, without being owners of the land, without remuneration; always as helpers, not even collaborators, never in charge of our own destiny,“ she adds.

“We are seeing that without women villages are dying out, it’s just a reality,” she concludes.

The co-ownership law and economic rights are only two of many issues that rural women currently face.

“The fight for gender equality, including within our agrarian organization, and against gender violence, is making us participate in different women’s councils and in protests so that the various administrations can change legislation,“ says Montserrat.

And ISMUR are also aware that their organisation alone cannot achieve gender equality.

National associations such as FADEMUR (The Federation of Rural Women) and AFAMMER (The Confederation and Federation of Rural Women and Families) are, throughout Spain, trying to to make rural villages a safer and happier place for women.

Locally in Segovia, ISMUR alone works closely with groups such as Segovia Sur, an association for rural development, UCCL, a union for rural people in Castilla y León, a union for females in agriculture, local and regional government in Segovia, volunteering and charity groups throughout the province and the wider feminist movement.

“We are very happy that other women have created new, similar associations and we will support them in whatever way we can,” says Montserrat.

“Many things don’t make sense if they are not shared. This is what we intend with other associations and collectives. But also on an individual level through formation and information,“ she adds.

This is because at the heart of ISMUR’s mantra is to make sure everyone in society plays their part in eliminating machismo.

Empowering women

“We cannot change that world in which we all are a part of by ourselves. The progress of society has to be through everyone; we all have to change our attitudes and learn. Because of this, we don’t solely work with women, and neither are our activities aimed solely at them but also at men and children,“ says Montserrat.

These activities include resources which inform women about employment, social issues and gender violence, whilst also educating men and children about gender equality.

“We are empowering women. We women are no longer as afraid to start our own business or participate in public life. We have higher self-esteem. We have worked very hard on these values,” Montserrat says.

And the last few years have indeed witnessed some positive steps towards gender equality, despite all the challenges.

“Right now, we even have a female president of an agrarian organisation in Burgos, an organisation which had been characterised for its sexism, but we were able to change that,“ says Montserrat.

“We are women who feel the rooting, the seeds, feeling like daughters of the land and proud of our ancestry, and thus responsible to conserve this heritage de hold on to the land and feel its link,“ she adds.

Looking to the future

In the end, rural women like Paola Biota in Valareña simply want to be able to live in the village where they grew up without any of the extra economic, legal and societal barriers they still face for being female.

“In spite of the problems, some of us have decided to stay here, whatever the cost. We keep fighting day after day for the village and its survival. Through the various village associations we put on activities for all our neighbours which helps develop unity between everyone. This is very wholesome, at least for me,” says Paola.

“We will keep fighting for all those people who are not here and built the village with their effort and sweat. Now it is our turn,” she adds.

“My village isn’t the place I want to return to, it’s the place I never want to leave.”