Climate change and female migration are two of rural Spain’s most pressing causes of depopulation. How is ecofeminism a possible solution to both?

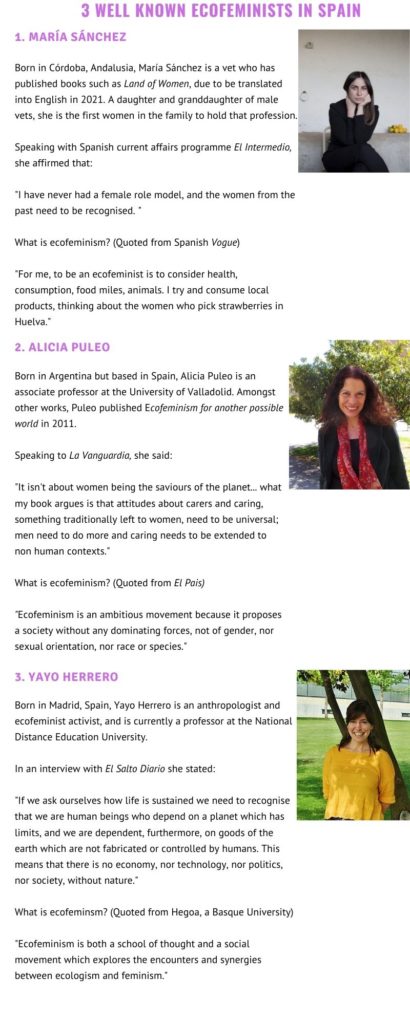

María Sánchez is an accomplished author and feminist activist from Cordoba, Andalusia.

She is most notable for publishing books such as Tierra de Mujeres (Land of Women) and Cuaderno de Campo (A Rural Notebook) and is passionate about inserting feminism and women’s experiences into contemporary Spanish rural literature, something which has, like many aspects of the rural world itself, hitherto been male dominated.

“I myself am a vet, and I work with indigenous species which are at risk of extinction, grazing or extensive livestock farming. Since I was little I have always loved to read and write, and I wanted to open a window to my day to day life and the world that I know through my books, because I saw a huge gap, and also an ignorance between the cities and our villages,” she says.

“I was tired of people always simplifying their images of the rural world into two extremes: we are either the “Holy Innocents” – hungry, poverty stricken, ignorant, brutal, traitors, assassins – or we are “Walden’s Cabin” – an unknown place, remote, idealised, where nobody bothers you-,” she adds.

Ecofeminism

And alongside the likes of Alicia Puleo and Yayo Herrero, Sánchez is one of Spain’s most influential proponents of ecofeminism.

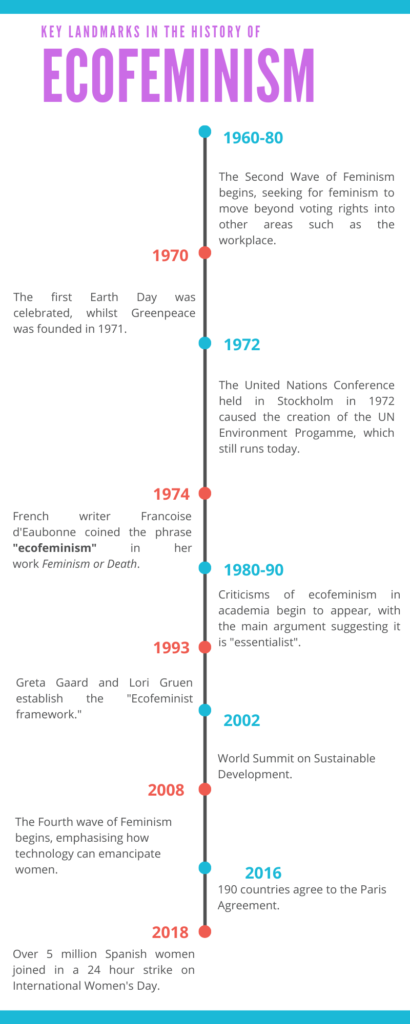

Although it has many complicated strands and off-shoots, an ecofeminist, in its simplest form, simultaneously fights for environmental sustainability and gender equality, believing that these twin issues are interconnected.

“For me, ecofeminism is a movement which allows us to get to know ourselves better, recognising ourselves as both ecodependent and interdependent,” says María Sánchez.

Sanchez, Herrero and Puleo’s works about the subject over the last 10 years have emerged within a context in which, despite decades of activism, climate change and machismo are still two of the biggest issues which modern-day Spain is grappling with.

In 2016, The Guardian reported that by 2100 the south of Spain could turn into a desert if the appropriate steps are not taken.

And since official records began in 2003, more than 1,000 women have lost their lives as victims of gender violence.

Climate change and gender inequality are also exacerbating trends of rural depopulation.

Indeed, two out of every three people who currently migrate from rural Spain are women, whilst environmental issues are also affecting two of its major sources of income: agriculture and wine production.

This is where, for its supporters, ecofeminism, a term coined by French writer Francoise d’Eaubonne in 1974, fits into the equation as a possible long-lasting solution to the triumvirate of gender inequality, climate change and rural depopulation.

“For me, ecofeminism is a way of seeing that the deterioration of the environment and the oppression of women are linked, and are due to the global capitalist and patriarchal system, which focuses on economic growth at the expense of life (human beings and other species),” says Beatriz Felipe Peréz, a researcher at the Tarragona Centre for Environmental Law Studies.

“The environmental crisis and the one already produced by patriarchy are crucial in the present day and are interconnected. In climate change migrations, for example, policies which are enacted to protect the people affected need to take into account that women face the impact of climate change and processes of migration in a different way, something we analysed in the 2019 work Perspective of gender in climate change migrations,” she adds.

By giving women proper recognition of the work they do, ecofeminism could help in rural Spain’s ongoing battle for gender equality.

“Without women, the rural world would not exist, or at least not in the way we know it. They have sustained it and made it possible to live in, most of the time without ever receiving anything in return. Their work has not been remunerated but has been invisible and without any recognition,” argues María Sánchez.

“They have been in charge of the upbringing, of being carers, of the house, the domestic tasks and also worked in the fields without ever being able to own anything,” she adds.

Despite the passing of the co-ownership law in 2011 by the Spanish government which meant that, for the very first time, women could be co-owners of agrarian land, one of the obstacles to rural gender equality is that its women are still hesitant to work.

“Many women still have to explain themselves to their husband or partner when they want to start a business, for example. A woman has to struggle past many more difficulties than men. Many are still scared of what people will think about them for wanting a little more independence, or to maximise their employment opportunities and skills,” Juana Borrega Izquierdo explained in an interview with Plataforma Voluntariado.

“During the pandemic, women’s responsibilities have multiplied, because as well as being nurses, cooks, administrators of the money spent inside the home, they have also maintained the emotional health of the family,” she added.

Ecofeminism as a possible solution to these issues

Thus, as a way of combating endemic problems of gender inequality, climate change and rural depopulation, María Sánchez believes that ecofeminism is a healthy solution for both women and the environment.

“For me to include this vision of life within our rural environments is fundamental, and we should go further. I like the term “agroecofeminism”, which takes into account the work done in the fields, respecting the interrelations between people, animals, seeds and lands,“ she says.

“This vision breaks with this idea that we are individual organisms who do not depend on anyone (such as the care done by other people) nor on anything (resources, territory, water and food…) allowing us, in the climate emergency that we find ourselves in, to find new ways of taking into account this interdependence,“ she adds.

“Silvia, a farmer and rancher in Alba del Campo and Santa Eulalia (Teruel), cannot stay at home because her animals need care, and thanks to them society can eat.”

Whilst the draft of the Spanish government’s 2021-30 National Energy and Climate Plan claimed that it was “strongly committed to a gender perspective”, this commitment was made within a renewable energy sector in Spain which is dominated by male employees, with only 26% being women, six per cent less than the EU average.

“The conditions [in rural Spain] are not favourable for women to have an independent life. For men, it is much easier, because a sexist culture is still around,” Juana Borrega Izquierdo explained to Plataforma Voluntariado.

The future of rural women

Yet, despite these challenges, María Sánchez is optimistic when it comes to the future of women in rural Spain and the battle to save the climate.

“The situation is changing, little by little. In Spain we have finally got the co-ownership law. The work of many associations and federations like FADEMUR is of vital importance,” she states.

“I see a better present, and the future is yet to be written but I see it as positive. All that I like about rural environments now, such as agroecological projects, consumer groups, conservation of seeds and indigenous species, movements in defence of our villages and against intense farming are all advanced and led by women,” she adds.

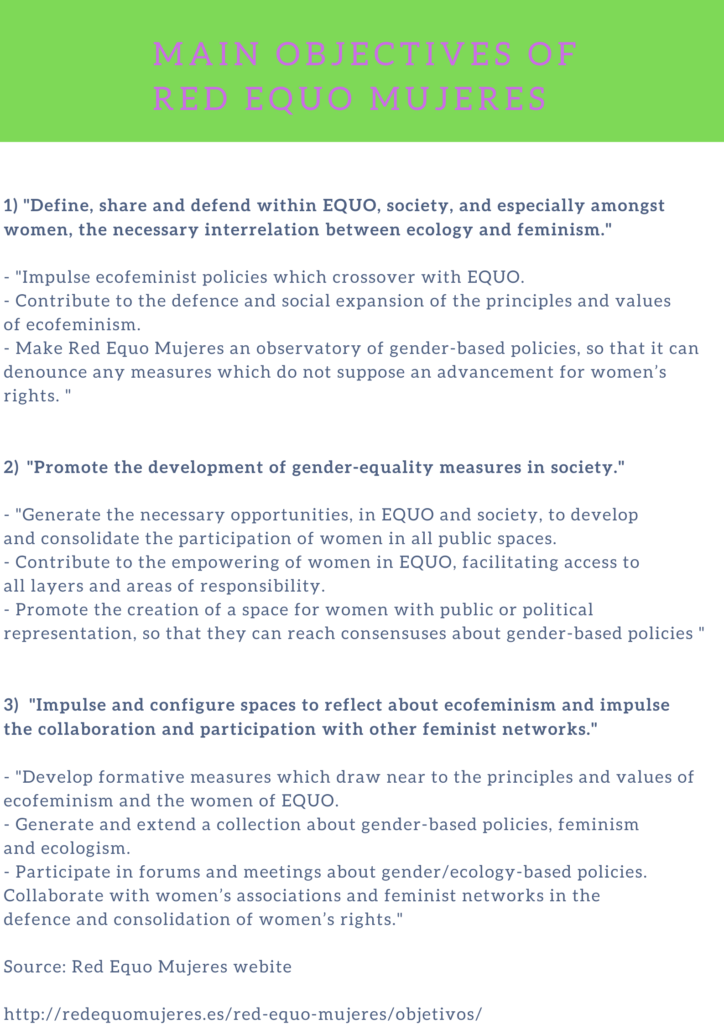

One such group is Red Equo Mujeres, the female branch of Equo, a political party founded in 2010 and a member of the European Union’s grouping of Green Parties.

Red Equo Mujeres believe that ecological and feminist-based policies are necessary in order for their overall aims of social justice to be achieved.

In 2017, Red Equo Mujeres gave an interview with Lucrecia Rubio Grundell and Xira Ruiz Campillo, published in a journal of International Relations.

“One of the main objectives that set the creation of Red Equo Mujeres in motion in a party like EQUO was that it could develop spaces in which to reflect about ecofeminism,” said the spokesperson.

“In a global context, where the poorest and most vulnerable collective is women, we can state that ecological problems, whether they come from climate change (drought, desertification and floods), or from extraction (mines or hydrocarbons), or industrial (overexploitation of resources, such as aquifers or forest stands), aggravate the gender inequality which already exists,” they added.

If ecofeminism attitudes are adopted, then perhaps women would be more likely to stay in rural areas, and the climate might be better looked after.

“I don’t think there is one rural woman, but many. They are diverse and different, and each of them has their own challenges, advantages and problems,” states María Sánchez.

For activists such as María Sánchez, ecofeminism could usher in a new period of rural repopulation by providing solutions to these challenges, as opposed to the depopulation rural Spain is currently experiencing.

It would, at the very least, present women with a genuine choice of whether they see their future in their rural village or not.

“And for me it is essential to be able to decide whether you want to stay in your village or leave. To simply have the right to choose,“ says María Sánchez