Research suggests we’ve been growing disconnected from the natural world, but the Covid-19 lockdown is turning many of us back to it. What has been so special about nature during this time, and will this relationship continue to flourish after the pandemic?

A morning spent in nature was unheard of for Vicky Charles before the Covid-19 lockdown.

Walking was purely for a purpose: getting her steps up to that 10,000 mark on her Fitbit, taking her 8-year-old daughter Samaire to and from school, or popping over to the local supermarket. She used to recoil at the bugs in her garden and couldn’t relate to her 8-year-old daughter Samaire’s desire to go camping.

“I didn’t really have a relationship with nature,” says Vicky, a freelance writer from Salisbury. “We’ve got a garden, but I didn’t really go out there very much – I just didn’t like it.”

But since lockdown began, some days the pair walk to a vast nature reserve, or on undiscovered paths around the edge of Salisbury. On other days, these strolls take them round the back of a community farm where they pass the time dipping their feet into the river, watching the horses on the other side, and spotting fish in the water.

“I’ve found that on days when I’m short-tempered, or my daughter is struggling with her own feelings, just getting outside and ending up surrounded by greenery can make a massive difference for both of us.”

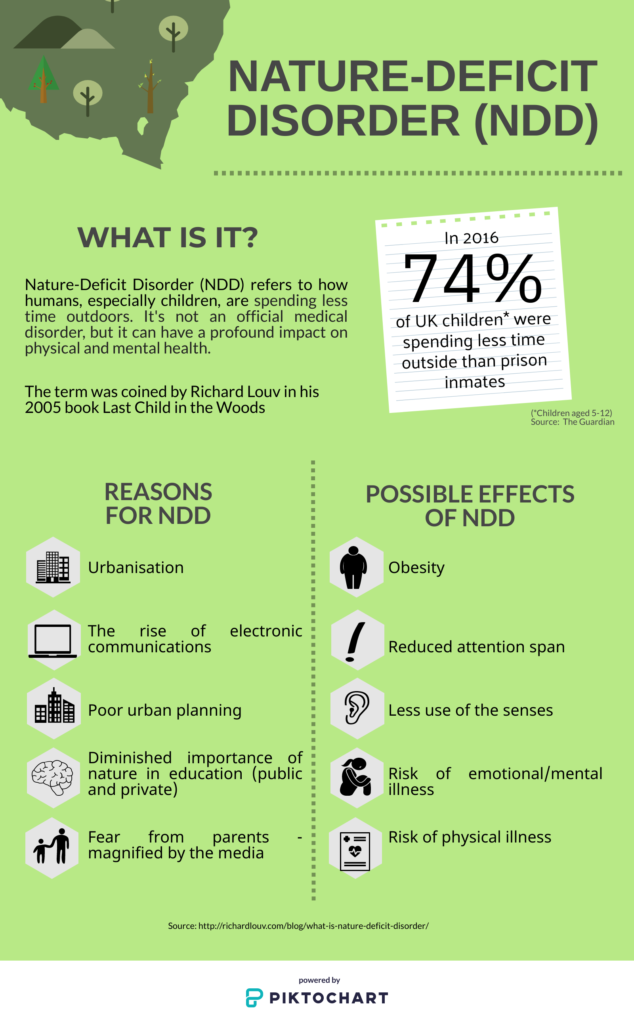

Vicky’s indifference to nature is not unique to her – an increasing body of research suggests that we have been growing more and more disconnected from nature since as early as the 1950s. Our lifestyles are moving indoors, greatly attributed to a rise in technology and urbanisation. A 2016 survey found that 74% of children aged 5-12 spent less than 60 minutes playing outside each day. And in 2017, 69% of people surveyed said they felt they were losing touch with the natural world.

Vicky’s discovery is one case amongst many Brits turning to nature during the coronavirus pandemic. Chloe Atkinson, a student at the University of Manchester, says that during lockdown back in Powys, Wales, she began birdwatching with her family. “We’ve got all sorts of birds coming along – blue tits, great tits, woodpeckers, buzzards, jays, magpies, even robins. I didn’t even know robins came out in summer,” she says.

Before the pandemic, a pocketful of birdseed on her way to her university building was the closest she had come to birdwatching. Lockdown allowed her the time to slow down and the chance to go back to living with her parents.

“I wouldn’t have been able to just get the binoculars out and watch them if I hadn’t moved out of the city and back to the countryside.”

Watching the woodpeckers swoop in to eat peanut butter off of pinecones on the elaborate birdfeeder has helped her manage her mental health.

“It’s nice to be able to perforate into the background and not have to think too much – a lot of my anxiety comes from overthinking, analysing things. But just to sit and watch birds… it takes it all away.”

The UK is increasingly turning towards nature. The RSPB say that more people are spotting birds in their gardens, a lockdown-particular project has seen amateur writers muse about the arrival of spring, and Chris Packham’s ‘The Self Isolating Bird Club’ Facebook group has grown to over 42,000 members. The purchase of seeds increased to the point of some businesses pausing sales to cope, with one London-based seller doing three weeks’ worth of sales in one day. Snowdonia also had their biggest visitor day in living memory in late March, according to the Snowdonia National Park Authority (SNPA).

Vicky found that Samaire’s tantrums over schoolwork could be remedied over an aimless ramble, and the pandemic has shown her the impact of nature too.

“It’s not until I started going out into nature more that I realised how much better it feels. It feels so free and energising.”

This appreciation of nature may alleviate the already dire projected mental health damage of the COVID-19 outbreak. In a study by University College London conducted during the pandemic, 35% of adults identified their mental health as being worse than before lockdown. When including young adults, people from BAME backgrounds and those diagnosed with a mental illness, this figure rises to 50%. Some experts even predict the mental health impact of coronavirus to outlast the physical health impact. The Office for National Statistics have also found that the rate of depression has almost doubled since before the pandemic.

We need nature for our health, says Professor Selena Gray, who is a professor of Public Health at the University of West of England.

“You need physical activity for 150 minutes each week, but you also need 120 minutes outdoors,” she says. “I think we live in such an urban environment that people have forgotten that that’s part of being healthy.”

Research from the International Journal of Health Geographics has shown that proximity to green spaces, such as woodlands, grasslands and the coast, has a positive association with good health. Nature has also been shown by Cornell University research to reduce stress, which is a major risk factor for developing a mental illness such as depression.

According to the Mental Health Foundation, 62% of adults in the UK found that taking a walk relieved some of their stress during coronavirus. Almost half of those surveyed also said that green spaces helped them cope with anxiety relating to the pandemic.

While engagement with nature has been shown to be important for our mental health, it’s something a lot of people are starting to recognise during the pandemic. Of those surveyed by Nature England during the pandemic, 41% of them reported that ‘nature and wildlife is more important than ever to my wellbeing.’

Professor Gray says that in addition to a lot of people having more time due to working from home arrangements or furlough, turning to nature during a crisis can also have a grounding effect.

“During a time of crisis, there’s something very powerful about looking outside of yourself and seeing the natural world go on as it always has done, even though things have changed for us,” she says. “And that’s been a great comfort I think – watching things.

“COVID and lockdown, for a lot of people, has forced them to live in a different way. And I think part of that different way is spending more time in their local environment and the outdoors.

“They’re recognising, for perhaps the first time, the value of them.”

This was the case for Vicky – with all the cafes, supermarkets and schools shut, she had to find another reason to walk. “Either you just stay in the house or you find another reason to go out,” she says.

But lockdown has had a polarising effect on access to nature – while it’s presented an opportunity for people like Vicky to start connecting with the outdoors, it’s left others stuck inside.

While 36% of adults reported to Natural England that they were spending more time outside during the lockdown, only 41% of adults reported in April that they’d gone outside at least once in the last week. Twelve months earlier, this figure was 73%.

From those surveyed in May by Nature England, the most-cited reason for not spending free time outdoors, was to prevent the virus spreading and/or due to the restrictions given by the UK government (63%).

But for Jean Fenton, this has presented an opportunity for her to find nature closer to home. Jean, a retired office administrator who lives on the edge of Dartmoor, has been shielding. With the exception of a short trip to her son’s house and a fleeting visit to the supermarket car park, Jean’s not ventured past the bench that sits just outside her door, or the communal garden shared with the 35 other flats in the complex.

“COVID’s had a massive detrimental effect,” she says. “I’ve been stuck inside my flat since March.”

While she usually finds herself on the moor, accompanied by her husband and a flask of tea, she’s had to adapt her interaction with nature to stay safe. Now, she sits on that bench and she listens to the jackdaws, watches the starlings nest in the guttering of the house opposite, and spies the hedgehogs scurrying by. Even when she’s inside, she incorporates natural material into her artwork and watches nature documentaries.

“If you don’t adapt, you’re going to be bloody miserable. You’ve got to find new ways to do the things you enjoy, or new things to enjoy.

“It’s become a goldfish bowl, but there’s still things in the goldfish bowl. There are still things to see to keep you connected.”

Post-lockdown, Jean thinks she will continue appreciating what’s around her home when in need of her nature-fix.

“I’ll be a lot more appreciative – even more than I was. I’ve actually been appreciating the nature that’s right on my doorstep rather than thinking I have to go right up into the moors to enjoy it.”

Academics have suggested that the pandemic can change our lifestyles, such as how we travel. However, it is still unclear whether this change will be sustainable. Research from the Health Psychology Review suggests that positive change can dwindle over time and that maintaining a change in behaviour can be difficult, as it depends on numerous factors such as resources, motives and social influences.

“Keeping mentally well doesn’t just involve exercising in a gym, it entails being involved in nature and the outdoors”

Professor Selena Gray

To ensure that this appreciation of nature as essential for our mental health is sustained past lockdown, changing the conversation around mental health to highlight the value of nature is one step health professionals and policy makers can take, says Professor Gray. At the moment, the heavily-cited Five Ways to Wellbeing – connect, be active, take notice, keep learning, give – do not reference nature as an integral part of our wellbeing.

“There needs to be an increase in recognition, for the public and for professionals, that keeping mentally well doesn’t just involve exercising in a gym, it entails being involved in nature and the outdoors.”

She says that this is also a concern for infrastructure, and we should be ensuring that everyone has access to nature, even if it is a balcony for potted herbs or relative proximity to a local park.

“I think the planning processes need to make sure that green spaces are part of all new developments,” she says. “There are some cities that have great access, but there are others where you can walk for miles without seeing a green space, and that’s not a healthy way of living.”

According to the ONS, currently, 12% of Britons don’t have access to a private or shared garden, with this rising to 21% in London. A recent study from the University of Exeter found that those with access to a private garden had higher psychological wellbeing. The limited access to private green space in cities like London makes access to parks even more important. Parks have been shown to improve the health of city-dwellers, but according to the Fields in Trust charity, the number of people living more than 10 minutes away (walking) from a park is projected to rise by 5% in five years’ time.

Post-lockdown, Professor Gray hopes that authorities will also be considering community-wide initiatives, from increased access to allotments and tree-planting schemes, to edible gardens in schools.

“There are a lot of opportunities for infrastructure that would provide jobs and also tangible outputs for improving people’s access to health and nature. […] I think it would be really exciting to see a really positive initiative like that.”

Regardless of any future nationwide change, Professor Gray believes that COVID has certainly impacted our individual perception of nature either way. “It’s been quite a powerful experience for a lot of people,” she says.

Vicky is at least confident that this revelation during the pandemic will at least improve her relationship to nature. Now, in the garden she once avoided, she and Samaire have three potato sacks, they’ve grown peas from seed, new celery is shooting from old stalks and nasturtiums are flourishing.

And, she’s kept up her walking – even if her step count is still on her mind.

“It occurred to me: you live in this city that is literally in the middle of the countryside, you can walk for five minutes and get to a place where you literally can’t even hear the traffic.

“Why would you get your step count in by going to Tesco?”