Since the pandemic has locked people in place, a retired history advisor has started walking the churchyard near his home. This led him on a discovery of dusty history.

The pilot flew low over his parent’s home and then hit high ground near Machen. The pilot was killed.

Flight Safety Foundation

This might be the finale of an air force pilot during World War II. What He owns now is a grave in the chapel yard of Tirzah Baptist in Michaelston-Y-Fedw, with a headstone saying, “HUBERT JAMES LEWIS HARRIS, Sergeant Pilot, Royal Air Force died 30th March 1940, aged 24”.

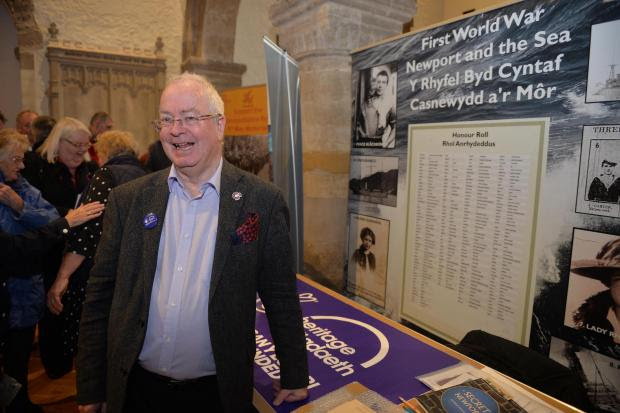

The task of discovering the truth falls to Andrew Hemmings, a historical adviser, now a volunteer of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). It is an organization aiming to mark, record and maintain the graves and places of commemoration of Commonwealth of Nations military service members who died in the two World Wars.

“There began a great adventure which is not yet finished,” said Andrew.

The first thing is looking for the site. The original Baptist Chapel no longer exists, leaving only the graveyard, which cannot be located even on Google Maps. Driving along the narrow country roads of Michaelston-y-Fedw, Andrew went from house to house asking for the exact location of the churchyard. Finally he found the cottage belonging to Mr and Mrs James.

The James couple are not related to Hubert Harris in any way. They are the current owners of the land. In fact, it could be said that Harris no longer has a single family member left in the world, according to Andrew’s knowledge.

Andrew’s clues came from the CWGC records and from documentation on the flight safety website www.flightsafety.org.

The CWGC records reveal the parents of Hubert Harris and that his grave is marked by a private memorial with the inscription ‘Lost his Life on Active Service’.

“I was curious to know more about this pilot, a quest that uncovered a story even more tragic than most casualties of war and conflict,” said Andrew.

He consulted the flight safety website. The details of the loss of an Avro Anson aircraft (the one Harris used for his mission) show that Harris was ferrying a plane from St Athan in south Wales to Sealand in north Wales.

“He was flying over his parents’ house, and he crashed into the mountain. His father was one of the first people on the scene.”

“That’s a very sad story,” said Andrew, “it was unknown if it was working, or it was an official flight.”

Andrew then traced the Air Ministry File into Sergeant H J L Harris killed: aircraft accident Lower Machen, Anson N9545, 1 Ferry Pool,30 March 1940. But the file was closed until April 2024.

He made a request to The National Archives and is now waiting for a copy to be sent in the post.

“Given the existing restrictions due to COVID 19, I have yet to see the contents. Later in the year I will update this account,” Andrew added.

Andrew Hemmings, born in 1947, was an adviser on transport policy to the Welsh Government. He was also Historical Adviser to the Heritage Lottery Fund films “Newport and the Sea: 1914-1918”. He is now a volunteer for the Kantor Speakers programme of the CWGC.

“I never knew my grandfathers. I always wondered what happened to them,” Andrew explained his interest in digging up historical stories this way. “I have got a degree in history, and there were various family stories none of which were particularly true. Somehow the war graves brought the two things together.”

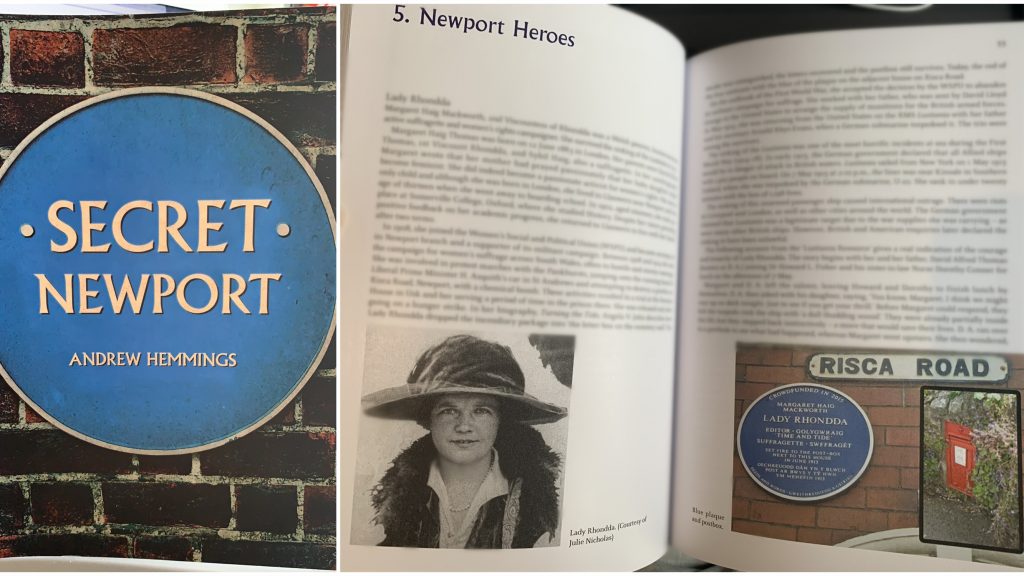

His interest in war casualties goes back to his childhood, but Andrew started his work on writing about the fallen and their headstones in his book Secret Newport in 2016. Around 2015 he accepted a commission from Amberley Books to write the volume ‘Secret Newport’.

“I was asked specifically to provide a chapter on Newport Heroes and determined to cast my net as wide as possible,” said Andrew, “in the event I included three women, five men, one boy and one horse.”

It was this experience that really opened his eyes to the extraordinary stories behind the ordinary people who either survived or died in the Great Wars. He began to explore churchyards and cemeteries for War Graves.

During the first few weeks of lockdown in 2020, he was walking through the churchyard of St John’s Rogerstone in Newport where he lives.

“For the first time I noticed a CWGC headstone from the Second World War,” then he read the details and started to explore the story behind the name V L ROBERTS, a volunteer who died 25th September 1940 at age of 23.

This was his first real encounter with war graves and writing stories for them.

“My first clues came from Shaun McGuire’s excellent website Newport’s War Dead and from CWGC records. The 13th Gloucestershire Battalion was designated City of Bristol Home Guard. I deduced that Vivian Lawrence Roberts was based in Bristol in 1940. The CWGC confirmed that Volunteer was the correct designation as the Home Guard was formed without formal Army ranks.

“At this point in my research I felt it unlikely that V L Roberts had died as a result of enemy action. As it turned out I could not have been more wrong.”

With help from family historian David Swidenbank, Andrew learnt that Vivian Roberts had married in the spring of 1939, living at Elsian 694 Filton Avenue in Filton of Bristol. Vivian was employed as a Tool room Miller at the nearby Bristol Aeroplane Company. More dramatically, David found precise details of the time and manner of his death on Wednesday 25th September 1940.

Jane Marley, Museums and Heritage Officer at South Gloucestershire Council sent Andrew digital copies of newspaper cuttings and eyewitness accounts of that fateful Wednesday afternoon.

“No doubt that Vivian Lawrence Roberts was killed by enemy action,” he concluded. Andrew compiled the story and published it in the local newspaper. Two of the surviving nieces of V L Roberts contacted him with more information about the family.

The biggest challenge in the research is the source of information. In addition to the official archives, the records of the cemeteries and chapels where the graves are located, family members are also an important part of the process.

“Sometimes the family want to tell people about their heroic ancestors and sometimes they don’t,” said Andrew. Some families wish to remain silent, and some will only tell part of the truth or stories that do not match the records.

He always needs to persuade these family members to share these stories and to constantly verify the truth of what he is being told.

What’s even more frustrating is that, these sacrifices have no family members left alive at all. William Henry Jenkins, served in Stoker Royal Navy, died in August 1946 is an example.

Andrew’s research revealed that although he died a year after the end of the war, the causes of his death included heart failure and coronary thrombosis, both of which were caused by the war. However, his service record, the ships on which he served and the battles he witnessed, are all mysteries.

On the entrance gate to the churchyard are two wooden boards. They hold a list of the names of those who died in the two world wars who lie in this cemetery. As Jenkins died a year after victory, his name does not appear on the boards.

(image: Ziyan Wang)

Andrew tried to find out if there were any surviving descendants of the brothers and sisters of William Jenkins but no results. That is why he publishes the stories he writes on websites or in newspapers.

The good news is, Mrs James said that some Australians had come to their backyard recently to look for traces of their predecessors. They were said to have come in search of their roots.

She said that many of the people from the coal valley went to Australia in the days when coal mining was on the rise. And now they are coming back to their roots, and perhaps among them are the descendants of the brothers and sisters of those who lost their lives in the wars. Perhaps the new family stories are unfolding.

For Andrew, writing stories for the war graves is not just a matter of interest.

It turns the stones into people. If you just go to a graveyard and see the headstones. They are just headstones with a name on.

“But when I look at the date of the death, I want to know what happened to them on that day. And if I want to know it, some people maybe also want to know,” said Andrew.