Mothers whose children were abducted and hidden by their ex-husbands are working together to close the Chinese legal gap. What is their future?

A joint letter, filled with names and case numbers, was sent to the Chinese government from hundreds of mothers whose children have been abducted and hidden by their ex-husbands, asking for legal provisions to make the act illegal and to define punishments to avoid further harm.

One year later, on June 1, 2021, Article 24 of Chinese newly revised Law on the Protection of Minors states that in divorce proceedings, one parent shall not abduct or hide a child in order to fight for custody.

“A lot of mothers are working together, and we just hope things will get better little by little,” said Xiaolei Dai, 41, a mother from Beijing who has been out of touch freely with her child for seven years.

Jing Zhang, a leading marriage and family lawyer in China, said the law clarifies violations but does not stipulate the consequences. Even so, it can be used to find fault with the other party in divorce proceedings.

But Dai is not particularly positive about the law’s effect. “It’s just been revised. It’ll be a long time before we see real results,” she said.

A campaign fighting for custody

Dai’s child was abducted and hidden by her ex-husband, Bailuo Bi, during divorce proceedings in 2014. For seven years, she almost never saw her child again. But she had no choice, because at the time, China lacked relevant laws and regulations.

In April 2016, she received a verdict from the first trial: the father who carried out the abducting was granted custody. Dai lost the case.

According to Zhang, whichever side lives with the child is more likely to win custody.

Still, Dai was not ready to give up.

From April to August of the same year, Dai specially rented an office and hired some assistants to help sort out materials and prepare for a new appeal.

“One day, they told me there were so many moms on the Internet asking for help in the same situation,” she said. “Let’s go and look for them.”

She created a group and these mothers joined in. “If it was with moms in my city, I would meet them face to face,” she said. “It’s the best way, because we can feel each other.”

In August 2016, they held a press conference and launched a campaign, Purple Ribbon, for them to help each other.

The joint letter that tried to push for legal change in China is a masterpiece of the campaign.

“We have a lot of volunteers, including mothers and lawyers,” she said. “Everyone can give advice about parental child abduction.”

Ying Wang, 40, from Chuzhou, Anhui Province, whose child was also abducted and hidden by her husband, Lou Qiao, also joined Purple Ribbon.

“They give me legal advice and recommend better methods that others have used,” she said.

Including Wang’s posts on the social media platform about her experiences, the campaign also found some influential people to help her forward them.

“It lets the local government see my business,” she said.

According to Wang, there are two effective methods for these mothers.

“The first is for the woman to get custody and then try to get the child back in the gentlest way possible,” she said. “Another is to negotiate with the man to give up the property and bring the child back.”

However, she abandoned the traditional approach when she learned through Purple Ribbon that the father who lives with their child is more likely to obtain custody.

“I will try to prosecute Qiao for having enormous wealth of unknown origin in his name,” she said. “I found a large sum of money in his bank account. The largest amount is 1 million yuan.”

Considering Qiao’s job, a staff in the government, Wang judged that he could not get such a high income. “I found all the bank records,” she said.

In her plan and imagination, if the evidence was solid and the prosecution succeeded, Qiao would face jail time and she would automatically meet her child again.

In addition to seeking help from the court, she also looks to government agencies – petition.

It is a way for Chinese citizens to express grievances, public opinions, or official deficiencies to governments at all levels. The Chinese government, the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference have departments to deal with such matters.

Rescued from desperation

Perhaps Li Zu, 32, who hails from the same place, Chuzhou, can show a glimmer of hope from the end of her child-seeking journey.

Two years after her child was abducted by her ex-husband, Zhang Di, she finally recovered her with the help of the court, the local People’s Congress and government staff.

She last saw her daughter in the summer of 2019, when she was away at work and communicated with her via video on her phone.

However, when she got home, she found the house empty – the child, husband, all gone. She filed for divorce.

At the end of the year, she received a judgment dissolving her marriage and gaining custody of the child. Still, she never saw her child. Her ex-husband would even prevent her from having normal contact with her daughter.

The judge cannot just go and forcibly take the child back, because under Chinese law, execution is usually directed against property, not against the person, according to Zhang.

“Judges keep saying children are not property, they can’t help it,” said Dai. “If there is no way to enforce it, why give us a verdict that there is no way to implement it?”

At her wits’ end, Zu turned to the People’s Congress of Chuzhou, Anhui Province, for help.

Finally, on September 3, 2021, the child was returned to her, accompanied by government officials.

Flying 8,000 kilometers

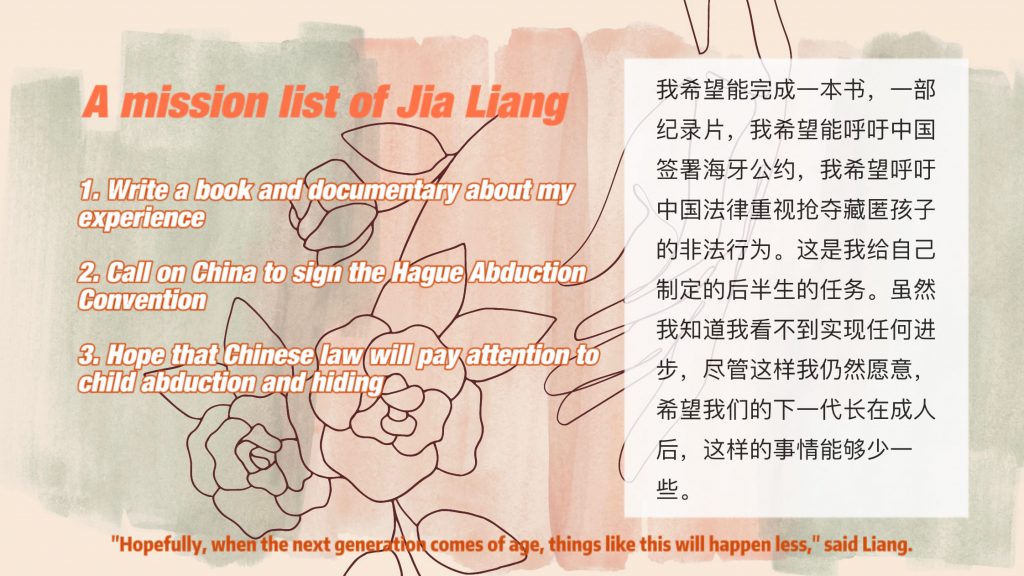

However, this route does not apply to Jia Liang, 34, from Beijing in China – she said her son was abducted by the biological father, Cao Liu, from China to France.

“Because China is not a party to the Hague Abduction Convention, the Chinese judges cannot help people directly bring abducted children back to his or her place of origin,” said Xiao Chen, a Chinese lawyer focused on custody cases.

The Hague Abduction Convention is a 1980 international treaty designed to protect children from custody violations. When a child is illegally removed, the States parties have procedures in place between them to ensure that the child is promptly returned to his or her country of residence.

Finding children abducted across borders in China, which is not a party to the treaty, apparently takes more time. For Liang, it took nearly two years without a court hearing.

She first sued Liu in China, and then sent the case to him in France through Chinese courts. After she waited for nearly 2 years, the judge told her that the cross-border execution had failed, according to Liang.

And, earlier, her child was not allowed to leave France for six months, following a French ruling.

“So I dropped the case in China,” she said. “The child can’t go back, and the verdict of the Chinese court is not recognized in France.”

She had imagined that if she could win custody in France, the baby would be returned to her, which meant she could get custody in China as well. “The Chinese judge has clearly indicated to me that he can award custody to whoever the child lives with,” she said.

However, compared with Liu, who works in France, Liang, who cannot speak French and has no stable residence here, was at a disadvantage in the first round.

According to the current ruling of the French court, the father of the child has been granted custody.

“For the sake of my kid, I’ll learn the local language and find a stable job to prepare for the next court session,” she said.

About the hometown she loves, “I can’t go back,” she said. “Although my friends, my family, everything I have is there.”

In this pursuit across thousands of mountains and rivers, Liang said the evil and good of human nature often make her feel very contradictory.

“Liu doesn’t see abducting the child from his mother as a problem, and doesn’t see the child without his mother as a problem,” she said.

But when she arrived in Paris, a stranger took her in for free out of sympathy for her plight. “She also has a daughter, and now we’re like a family,” she said.

Although ‘brave’ and ‘great’ are two words that many people use to describe these mothers, Liang said:”I really just want to be a very ordinary person and live a quiet life.”

She just got back from a two-hour meeting with her son. The foreign woman stood on a railway station in this small town, preparing to return to her temporary home in France.

“It feels like life is full of ups and downs, and I don’t know if it was meant to be,” she said.

Tears suddenly fell from her eyes and she covered her face.