The UK has abundant geological coastal dating back to hundred million years ago. In summer, beaches are not only a place to enjoy sunbathing, but also to learn about how life evolves on the Earth. Walking down the beach, you may find fossils on some common stones.

Covered by the sea in middle Jurassic times, the greater part of South Wales was in the shallow, sub-tropical waters where life was abundant and varied. Ammonites, baculites, and ichthyosaurus swam through the clear and rich ocean.

Inspired by the Ammonite, a film about the life of British paleontologist Mary Anning played by Kate Winslet, I decided to find my first fossil. Mary Anning was an English palaeontologist and found the skeleton of an ichthyosaur a large extinct marine reptiles lived in Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods. Her findings made a profound contribution in scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the history of the Earth. However, as a woman, Anning was not able to fully participate in the scientific community of 19-century Britain. She even did not always receive full credit for her scientific contributions.

Although Anning had financial difficulties much of her life, she persisted with her career in finding fossils. The excitement of finding fossils can only be understood by trying it on your own.

Finding fossils is not an easy hobby that you can start with nothing prepared. I should look up some professional information about geology and palaeontology to find a place where I have a high possibility of fossil hunting.

It was a cloudy Wednesday. I was walking underneath the cliff of the Jurassic coast of the Dunraven Bay. The rugged coastline is covered by various sizes of round stones. Maybe I was motivated by my mission of finding fossils. I jumped from one stone to another as if I were walking on flat ground. After arriving at an area with many small cobbles, I stopped at a big rock, hoping to spot any fossils on it but nothing to find.

“Look for, in this case, pale curved lines, circles, spirals, or similar. Most long straight lines are just mineral veins or fracture patterns,” said Cindy Howells, a palaeontologist of the National Museum of Wales. I continued to walk deep alongside the cliff. At a corner of shallow water, I turned every stone around me. Suddenly, I saw a dark-brown curved line on a gray cobble that looks like a snail embedded in the stone. It is my first fossil. I was excited as I never thought that I can find a fossil just after I arrived which made me feel the Dunraven Bay is a treasury of fossils. I can imagine two hundred million years ago, various kinds of ammonites throve on the seabed, but suddenly become extinct because of natural disaster and now one of their bodies is on my hand.

I sent the picture of the little stone to Cindy. “The little spiral stone is a tiny ammonite which lived 200 million years ago in the Jurassic times,” Ammonites were relatives of today’s octopus living, like the modern nautilus. They lived in the Mesozoic Era (251-65.5 million years ago), preying on smaller marine animals. They usually had a spiral shell which could be from 5mm to 2m across.

Over the last few decades, fossil collecting has grown profoundly popular all over the world. The excitement of discovering fossils is understandable: it requires practical skills of collecting and preparing specimens, and the academic challenge of identifying fossil finds. In addition, you never know where there is a well-preserved fossil. Beginners can also make great contributions to the study of Earth’s extraordinary pre-history.

Therefore, I visit the National Museum Cardiff and the Bristol Museum to have a basic understanding about what fossils are commonly found in southwest Britain. There are many small ammonites that are sold in the gift shop of the Bristol Museum, which is a good way to learn about fossils. Also, palaeontologists of museums are very willing to help people recognize fossils. You can contact them from the website of your local museum.

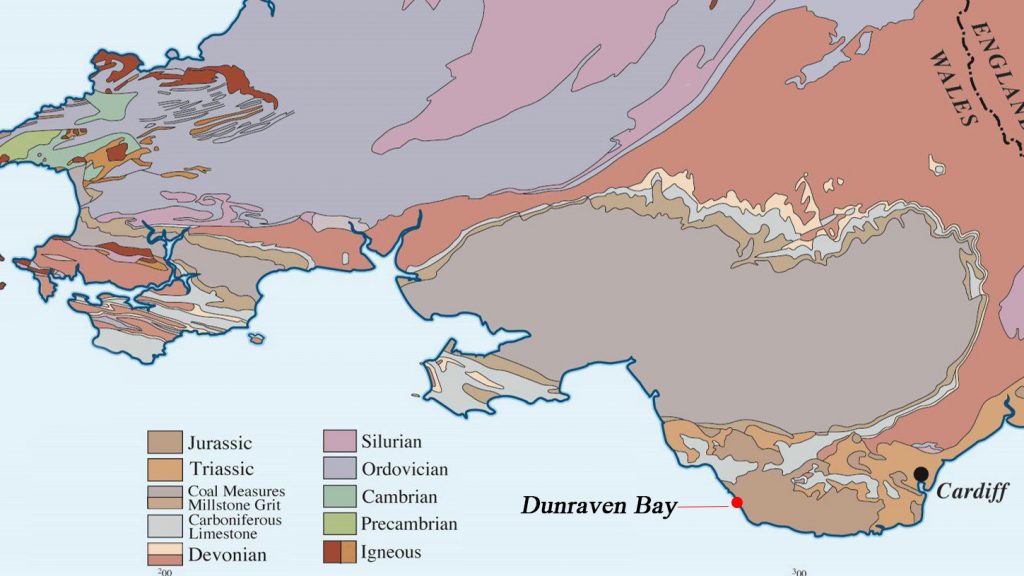

“Basically finding fossils is a matter of recognising shapes in the correct types of rock.There’s no way of finding any fossils if you’re looking in rocks that don’t contain any – so that’s the first step,” said Cindy Howells.

In 2020, Cindy just investigated dinosaur footprints in Penarth. According to her, two hundred million years ago, in the early Jurassic period, southeast Wales was covered by a warm shallow sea, teeming with life. She advised me to look up sites such as Penarth, Ogmore or Southerndown.

“When you pick up a fossil on a beach it is often broken or eroded. You might discard it because it is poorly preserved or incomplete. But most fossils are found partially concealed in rock, and in these cases they can carry hidden secrets,” said Cindy.

Wave-washed cliffs and foreshore exposures are good places to search for fossils. Dunraven Bay, also often referred to as Southerndown beach, is a Jurassic coastal of South Wales, where I think is an ideal place to find fossils. Here, you can escape from the busy city life and get close to nature to immerse yourself in talking to prehistoric creatures.

Looking from the cliff from the Dunraven Bay, I saw the Blue Lias, mostly thickly bedded limestones with shale bands. It is a typical geological formation in South Wales, which consists of a sequence of limestone and shale layers, laid down in the latest Triassic and early Jurassic times, between 195 and 200 million years ago. Fossils, especially ammonites are always found in the Blue Lias. The bay is covered by various sizes of round stones, which probably have fossils inside. It is difficult to maintain a balance when walking in a place like that.

There are several fossil collecting tools you can bring for your adventure. But as a beginner, in case that I would damage any fossils, I think searching and observing are the best way to start this hobby. There are many Bivalvia fossils on the rock alongside the beach. Bivalvia is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs including clams, oysters, cockles, mussels, scallops, and numerous other families that live in freshwater.

The clusters of Bivalvia encased on the rock and the arch-like shape anticline tell a story that hundred million years ago, there was a strong earth movement that happened in this peaceful beach. The magma burst out from the volcano, melting the rocks and flew down to the beach. The Bivalvia were killed in a second. When the magma cooled down, the Bivalvia were encased in the rocks. After two hundred million years washed by waves, the big rocks became cobbles and the Bivalvia emerged again.

The little ammonite fossil gave me confidence that I could find more fossils on the bay. So, I kept walking inside. I was amazed by the shale and could help stop to touch them with my bare hand. It felt like I was touching the Jurassic seabed and many marine plants and animals were gently shaking run through my fingers.

I was about to lay down my bag in order to have a look at the bottom of the shale. Surprisingly, I saw a snail-shape stone in red-purple color with a coarse growth ridge. Cindy told me that it is a gryphaea, also named devil’s toenails. They mostly lived in Triassic and Jurassic times and are particularly common in many parts of Britain. They lived on muddy seabeds, originally cemented to a small particle of rock by its tip.

My first journey of fossil hunting is inspirational and educational. Although my two fossils are commonly found in Welsh coast, they also ‘bring me back’ to Jurassic world. Touching them gives me a surge of emotion as if they were telling me how life evolved on the Earth. This experience told me that it is not a difficult thing to start a scientific hobby. In addition, I can also feel the power of nature. Every species is just a guest of this planet. The earth can give us life but also it can take it back. Maybe sometimes, the trace of humans could only be found in the rocks.