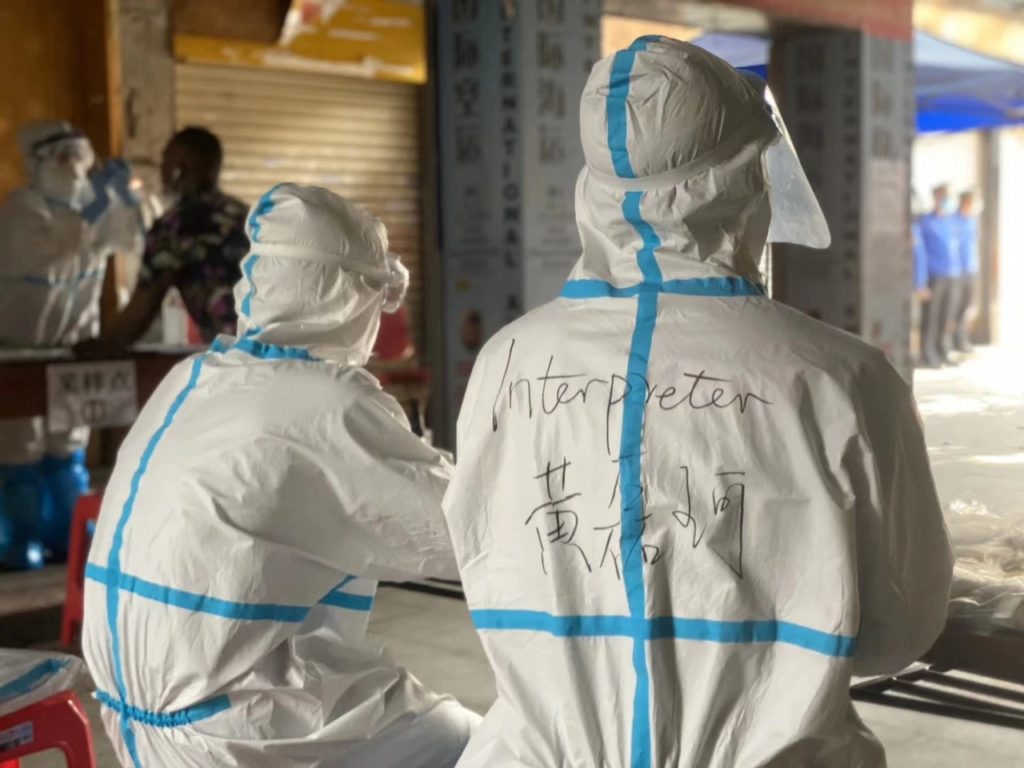

While the Chinese authority confronted Africans, miscommunication often took place.

Xiaotian was informed by a Chinese-African couple that the police affixed a seal on their door on April 4. They said they were tested four times within one day.

While walking on the street, Xiaotian could see some homeless Africans roaming under the highway overpass. He approached them to ask what happened to them. Some said they were evicted by their landlords, while some said they had been rough sleepers for months.

Around the same time, anthropology researcher Laoyao knew from her African informants that they were thrown out of the apartment and had nowhere to go. She also saw videos going viral on social media that local Chinese were discriminating against their African neighbourhood.

Those scenes took place in Guangzhou, a commercial hub in southern China. The city hosts the largest African community in Asia, whose population is estimated at 15,000 to 25,000. As the capital of the Pearl Delta Region, also known as the “world factory”, Guangzhou also attracts many African traders to bring Chinese goods back to their home countries to sell despite many of them being knock-off ones.

As Covid-19 swept over China, the multi-ethnic trading scenes nearly vanished, while xenophobic narratives began to take over. Guangzhou’s imported cases provoked fear that Africans might carry the virus, thus many of them were displaced.

Sleeping on the streets, the displaced Africans in Guangzhou felt they were put in limbo as the southern China city is experiencing the rainy season.

Laoyao felt an urgent need to help the Africans, so she gathered a couple of anthropology students who had African informants in Guangzhou, including Xiaotian. They organized a volunteer team that expanded to a few hundred people via online recruitment.

Laoyao wanted to address the difficulties of evicted Africans at first. She knew Africans had internal networks to help their fellows. She assigned a few Chinese volunteers to team up with Africans, delivering food and contacting accommodations for those kicked out by their landlords.

Xiaotian led a news team to update information for Africans. He registered an official account named atSanyuanli on WeChat, the prevalent social media in China. Initially, he published the articles briefing news and refuting rumors.

The first post was about a bulletin from Guangzhou Police Information Office. A rumor spread by a 42-year-old Guangzhou resident claimed two foreigners had escaped with novel coronavirus pneumonia, which was proved false by the police.

The article also translated the official statement from the local authority. “Given the current epidemic prevention and control work, the Guangzhou Municipal People’s Government has always put the lives and health of the citizens and foreigners in the first place, treating Chinese and foreigners equally, and strictly enforcing the quarantine rule for people entering the country, confirmed cases and people in close contact,” read the bulletin.

The statement provoked outrage from the African audience, which could be observed from the comments.

A comment that earned most likes said, “Can Africans have their home back now please?”

“Even if they (Africans) disobeyed orders, why not use the humane due process rather than kick them out to the street in that ungodly weather? Why my dear Guangzhou, why do you sadden humanity to that extent,” a user named Isaac commented.

Xiaotian didn’t expect their first post would aggravate Africans. Many of whom begged the answers for why they were mistreated and forced to quarantine. “We were blamed as pro-Chinese government,” said Xiaotian. “If you are Chinese, you can’t avoid that perspective, even if it is not intentional.”

While aiming to lend a helping hand, Chinese volunteers felt they were misunderstood at times. Laoyao said she was suspected while promoting her voluntary work in a group chat with a majority of Africans, as they thought she “was sent by the police or was spying”.

She sent the first article to the Wechat group, but countered unprecedented mistrust from the Africans. She knew them since she did her ethnography four years ago, but they formed another African-only Wechat group later. “I asked my Niger friend if he could add me in the group, he said they won’t let me in,” said Laoyao.

As the communication effect was not so sound as expected, Xiaotian perceived that Africans may need useful tips to pull through this tough period rather than the daily news brief.

The news team made a post explaining how to use Suikang Code- an electronic health code issued by Guangzhou Municipal Government to trace people’s health status and travel history. Without the Suikang Code, people would be banned from entering public places, such as metro stations, parks, markets, residential communities, etc.

However, African residents in Guangzhou were not notified to register a Suikang Code via WeChat, thus their mobility was restricted. While the Suikang Code could be registered with multiple languages including Chinese, English, French, Japanese, and Korean, there was little non-Chinese information on WeChat guiding people on how to register and activate the Suikang Code. The article published by Xiaotian’s news team filled the information gap with detailed guidance in English.

The news team then extended their “how-to” guidance to issues regarding visa expiry, accommodation, food, and transportation, etc. Since some Africans were new to the city, they barely knew WeChat and Meituan, a food delivery app commonly used by Chinese. The guidance showed how to download and use WeChat and Meituan. Also, the guidance listed embassy hotlines, flights between China and African countries, and quarantine hotels for foreigners.

The volunteer team also collaborated with the neighborhood committee ,China’s community-level administration,to provide counselling sessions to Africans. They opened the hotline from April 20, and was soon overwhelmed by African’s inquiries.

“Africans had no money to buy food. They didn’t know where to stay. They were rejected by taxi drivers, shop owners, landlords, ” said Qiaomu, the coordinator of the hotline program. “They vented feelings, and we barely knew how to answer their questions. That was why we worked out the ‘how-to’ guidance.”

Wuchuan, a volunteer of the hotline program, said she came across emotional reactions while calling Africans.

Some questioned the mistreatment. Wuchuan recalled an African woman called her at 2 am while she was rejected by a 7-11 convenience store. On the phone, Wuchuan could hear the lady was quarrelling with the shop assistants. “It’s the most racism I see since I was born,” said the woman.

Some expressed their antagonism towards Chinese. “My sister I’m sorry you’re Chinese but this was unbelievable. Your people have no love at all,” Wuchuan quoted an African caller.

Some cried on the phone. “One cried really long. He said most of the hotels rejected him. The ones accepting him were unaffordable. He has run out of money,” said Wuchuan.

Apart from comforting Africans, Wuchuan said the team had to inform Africans to do Covid-19 tests 7 days and 14 days after they leave their quarantines, which was mandated by Guangzhou’s authority. Many Africans asked why they needed to do so many tests, but Wuchuan couldn’t give a clear answer.

“I could see the local authority was quite scared of the new cases, but different departments were not fully aware of their responsibilities,” said Wuchuan. “There was no written document telling the grassroot staff what to do.”

Xiaotian could reiterate that from the experience of his African friend Chuk. Chuk was ejected by his landlord. He called Xiaotian to accompany him to do the Covid-19 test. While waiting for the test in front of a trading mart, they were reported by the neighborhood committee.

“The government ordered all Africans should be accommodated in hospitals or hotels. Anyway, no Africans should appear on the streets,” said Xiaotian. “The community-level administration worried they might fail the job.”

Pressured by the neighborhood committee, the police had to bring Chuk to his apartment and required the landlord to accommodate him. According to Xiaotian, Chuk felt lucky to be able to quarantine in his apartment rather than sleep under a bridge.

“If an African was infected, the community would be sealed off, and the neighborhood committee would take the responsibility,” said Xiaotian. “Amid the fear that Africans were virus carriers, many neighborhoods felt reluctant to accommodate them.”

Laoyao said the collaboration among different departments was like “kicking the ball to others”. The grassroot official didn’t know how to treat Africans as there was no official document, and no one was willing to take the risks. And sometimes, it was not all about racism.

CNN reported African students alleged brutal policing against African in Guangzhou. The video showed a black man was tied by a few policemen. It is easy to conclude the policemen’s misconduct as institutional racism, but it is not the whole picture.

Xiaotian said the grass-roots units were under incredible stress to do their jobs. “The police had KPI for their districts. They need to make sure no Africans would appear on the streets. They had to finish their tasks in a short period, probably overnight,” he said. “Because of the language barrier, they couldn’t communicate well with the Africans, which led to maltreatment against the group.”

China has been taking radical measures to prevent the resurgence of Covid-19 cases. Chinese citizens tend to follow the government’s instructions, voluntarily doing self-quarantine, using health codes and taking nucleic acid tests. The national mobilization turned out a success in terms of containing the outbreak, but it met challenges while applied to foreigners.

Wuchuan said China was using domestic policies to manage foreigners during the pandemic, which was problematic. While Africans have come to the city since the 2000s, either the authorities or the local residents have little cultural understanding of their African neighborhood.

Gordon Mathews, anthropology researcher at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, found Chinese tend to think “China is for Chinese” through his ethnographic study in Guangzhou. In his book The World in Guangzhou: Africans and Other Foreigners in South China’s Global Marketplace, Gordon wrote about a Central African Cam. He has long-term Chinese residence and good relationships with local officials, but he said the Chinese always called him wai guo pengyou, foreign friend. Cam maintained the emphasis is on “foreign” more than on “friend”.

Wuchuan said “prejudice is born from ignorance” in an article she wrote for The Paper, a major Chinese publication.

“The average living standard in Nigeria is $2 per day. Many people make their lives through informal sectors,” she said. “There is limited space for upward mobility in Nigeria, so Nigerians try their best to make a living outside, including China. Many people I met in the markets asked me if I could get a Chinese visa for them.”

She stayed in Nigeria for one year. She said she never experienced an electricity blackout before coming to the eastern African country.

“The most important lesson I learnt in Nigeria is that there are so many people who are more courageous,diligent, and talented than me, but they are trapped by their fates. They could never make a way out of their sufferings and become the buried gold. However, many people tagged them as ‘losers” or “marginalized”, thinking they are bound to those miseries. That is the lack of understanding and empathy,” read her article on The Paper.

“If our media could report more about how Africans are changing their communities, if the Chinese staying in Africa could tell the lively story of this continent with more empathy, if we can broadcast the films from Nollywood one day, I believe the shadow of racial discrimination will be thinner.”

Laoyao said she missed the time of her ethnographic study a few years ago. “The interactions between Chinese and Africans were vibrant. People made jokes and chatted happily. They had conflicts at times, but wouldn’t elevate them to political tension or racism, “ said Laoyao. “But now, the diversity of perceptions is fading away. People classified themselves as ‘Chinese’ or ‘African’, and there was no third option.”

While helping the evicted Africans on the street, Laoyao received racist comments on WeChat. She felt frustrated but didn’t abandon the efforts to support more Africans. “Maybe we could be a force to alleviate the tension between China and Africa,” said she.

(To protect the security of interviewees, Xiaotian, Laoyao, Qiaomu, Wuchuan and Chuk are pseudonyms.)