Despite causing pain and infertility, why is it so difficult to receive endometriosis diagnosis in the UK?

Endometriosis is a condition that affects an estimated one in ten women, causing chronic pain, infertility, and a severe impact on quality of life. Despite its prevalence, women in the UK often face lengthy NHS wait times and frequent misdiagnoses, leading to prolonged suffering and frustration. 29-year-old Ella’s journey is a testament to the systemic failures within the NHS.

Ella was only 13 when the excruciating pain first struck her. She fainted in chemistry class, waking up to a haze of agony and confusion. Her parents rushed her to the GP, but the relief she sought would remain elusive for another nine years.

“From the moment I started my period at age 13, the problems began,” she says. “The pain was so intense I had to take off at least a day a month from school. My head of year told me not to make a habit of it.”

Ella was diagnosed with endometriosis in 2019. After years of being dismissed and misdiagnosed with conditions like IBS (irritable bowel syndrome), she finally insisted on being tested for endometriosis. Even then, it took multiple appointments and a lot of persistence before she was referred to a specialist.

Her diagnosis was confirmed through a laparoscopy, revealing extensive endometriosis throughout her pelvic cavity and on her bowels. However, despite the surgery, her quality of life has not improved significantly. She was told not to take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain, so she relied on painkillers. However, because it’s a restricted medication she can’t function at work when she takes it. “My doctor says it’s too soon for surgical management again, and hormones are the only medical treatment right now, but the suicide risk for me is high, so it’s not sensible. I’m sort of stuck right now.”

Lauren, a 30-year-old hospitality manager from Abergavenny, shares a similar story of pain and perseverance. “I’ve always had extremely heavy periods since I was 14,” she recalls. “Doctors prescribed me mefenamic acid as a teenager to help with my symptoms, but nothing was ever mentioned about a cause.”

In her early 20s, after a private consultation that dismissed her concerns, Lauren continued to suffer. It wasn’t until she moved to England and collapsed, resulting in a three-day hospital stay, that doctors discovered an ovarian cyst. “I was given painkillers and sent home with no follow-up required,” she says.

Frustrated and feeling unwell for months, Lauren sought another private consultation, which finally led to a laparoscopy confirming endometriosis. “The relief of finally having that diagnosis was overwhelming,” she says. Despite undergoing surgeries to remove the endometriosis, she continues to worry about its impact on her fertility. “I had a miscarriage a few months ago, and it makes me wonder how much endo had to do with it.”

But why is it so hard to get diagnosed with Endometriosis?

Helen Evans, a Clinical Nurse Specialist for endometriosis and pelvic pain, acknowledges the difficulties women face in getting a diagnosis. “Endometriosis can present in many ways for different people,” she explains. “Being able to have the time to establish a full history of a patient is paramount in developing an understanding of their past medical history and their symptoms,” she said.

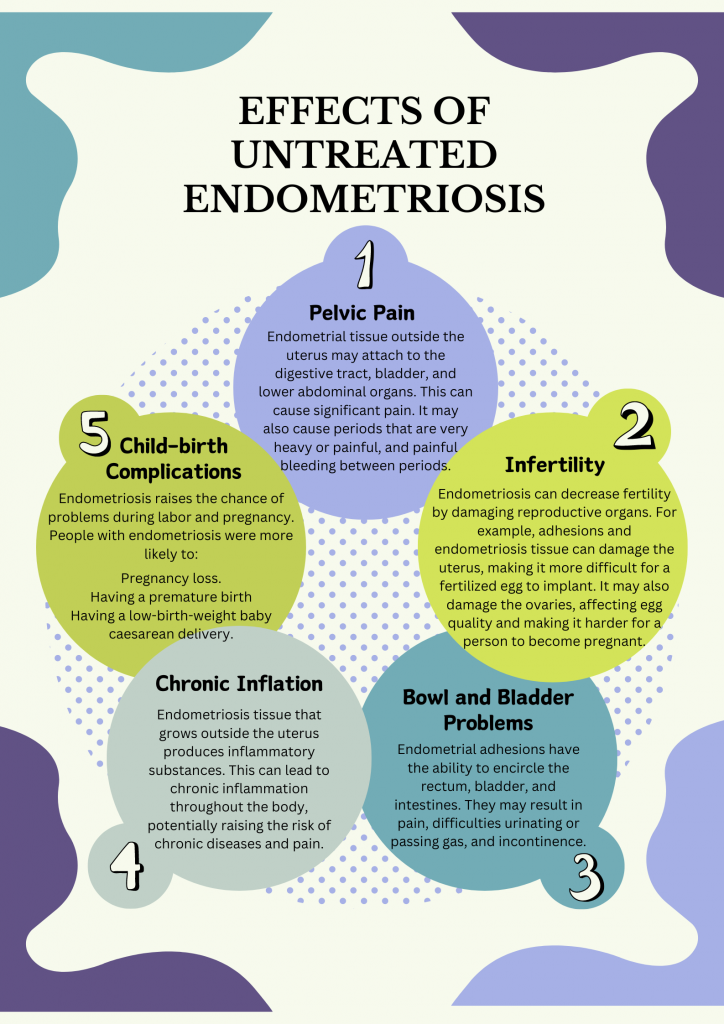

She further explains how Endometriosis symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating and constant fatigue can easily be confused with other illnesses like IBS. However, she also points out the systemic issues within the NHS that contribute to delays. “We have a growing population but stagnant or even declining NHS services in some areas,” she says. “Staff are going above and beyond to deliver good quality care, but capacity, access to theatre times, and provision of staff are being pushed to the limit.”

Gabz and Anna, founders of the Menstrual Health Project, are actively campaigning for better support and recognition of conditions like endometriosis. “At 10 years old, I started my periods, which were incredibly painful and debilitating,” says Gabz. “I spent my teen years in agony, constantly missing school and struggling with my mental and physical health.”

Gabz’s story echoes the frustrations of many women who feel dismissed and gaslighted by healthcare professionals. After years of being told her symptoms were normal or misdiagnosed as IBS, she finally found a GP who referred her to a specialist. “In March 2016, I had my first laparoscopy where endometriosis was found on my bowel and left ovary,” she says. Despite undergoing multiple surgeries, Gabz continues to suffer from chronic pain and other complications.

Anna’s journey began similarly early, with painful periods starting at age 11. “I was experiencing rectal bleeding, pain passing bowel movements, and chronic fatigue,” she recalls. After being dismissed by a gynaecologist, she was eventually diagnosed with endometriosis following an emergency surgery. “I’ve had 16 surgeries due to the disease, including living with two stomas and early menopause,” she says.

Both Gabz and Anna emphasize the devastating impact of misdiagnoses and delays in treatment. “Misdiagnosis can have long-term impacts, especially if the disease is progressive,” Gabz explains. “The damage delays can cause can be irreparable, leading to organ damage or loss.”

Anna adds that society’s reluctance to discuss menstrual health agravates the problem. “We are made to feel that talking about our body and health is taboo,” she says. “There is still not enough education about what’s normal and not normal, and the red flags to be aware of.”

The Menstrual Health Project is working to change this narrative by providing educational resources and advocating for a multi-disciplinary approach to endometriosis care. The founders of the Menstrual Health Project were frustrated by their own experiences with endometriosis, so they cofounded it. They intended to offer a voice to those who struggle to get care and support for a variety of menstrual health disorders, emphasising how these conditions can affect the entire body and a person’s life. They produce free and easily available educational resources, which are carefully vetted by both patients and medical specialists in the field.

“We need to reclassify endometriosis as a whole-body disease, not just a reproductive disease,” Gabz insists. “It is imperative that our health system is proactive rather than reactive when it comes to conditions like endometriosis.”

Their collaboration with BeYou, a company supporting their educational initiatives, aims to create accessible resources for those navigating menstrual health issues. “The toolkits are our love letter and compilation of all the information, guidance, advice, and support we wish we had when we were younger,” Gabz says.

The stories of Siona, Lauren, Gabz, and Anna highlight the urgent need for improved care and support for women with endometriosis. The NHS must address its capacity issues and ensure timely access to specialists. Medical professionals need better training to recognize and diagnose endometriosis accurately. Finally, society must break the stigma surrounding menstrual health to empower women to seek help without fear of dismissal.

Until these changes are made, women with endometriosis will continue to suffer in silence, their lives disrupted by a condition that deserves far more attention and understanding. As Gabz and Anna’s work with the Menstrual Health Project shows, there is hope for a better future, but it will require concerted effort and commitment from all corners of society.