Northern Ireland’s government has been suspended since May 2022 as a result of a dispute over Brexit which has added to the issues around its constitutional question. What does this political turmoil mean for the peace process and for people on both sides of the divide trying to deal with the legacy of the conflict?

Today just thirteen kilometres from Belfast city centre, the remains of the old Long Kesh Internment camp consist of a desolate 350-acre site with just one of the old H-blocks still standing.

The expansive maximum security complex once housed the paramilitaries responsible for the destruction of Northern Ireland. It was also the site of the republican hunger strikes that dominated the media in early 80s Ireland.

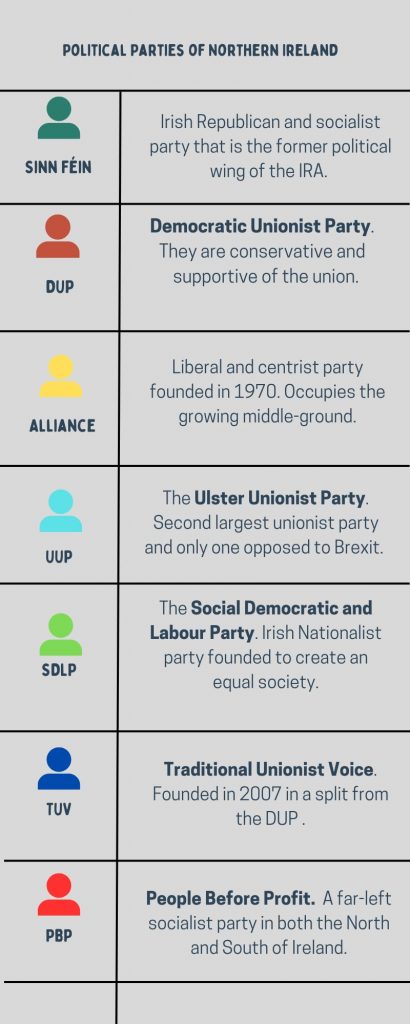

Many plans for its use have been proposed down through the years – from a sprawling shopping complex to a peace centre but neither of the North’s two largest parties, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) nor the Irish republicans Sinn Féin, can agree on what should happen.

Now with a government on hiatus since May 2022 the site’s future remains as unclear as ever.

“If you ask me they should just knock it down and move on,” said the young security guard manning the site office where the prison entrance once stood.

“We do enough talking about the terrible things that went on in this country, sometimes we just need to accept what happened and move on together but nobody knows what can be done because we need to have a working government first.”

The remains of Long Kesh prison represent Northern Ireland as a whole. A state that is paralysed by its past despite the appetite to move on and create a better future. Its failed regeneration is symptomatic of its dysfunction. A ghost of the past that continues to haunt people today with the horror of the violent conflict remaining visible for all to see.

This trauma has only been worsened by Brexit. It has forced the polarisation of society and politics and has led to a total stalemate in government. This means that places like Long Kesh and other shadows of the Troubles exist in a state of limbo and weigh heavily on the psyche of those who lived through it and see them every day.

One such place is in the border village of Crossmaglen. Its pristine town square is spoiled by the rusting decrepit remains of the imposing British army barracks. Built on land requisitioned from the town’s Gaelic football club – the pride of the parish of Upper Creggan, the club continues to fight to get back for what is rightfully theirs.

This is a fight ongoing for over 40 years. Much like Long Kesh, the barracks remain a constant reminder of the past, preventing the people of Crossmaglen from confining this sad chapter to history.

“We don’t have a government and we’re all suffering as a result in the North,” said Róisín Murtagh, the public relations officer of Crossmaglen Rangers Gaelic football club.

“The economy is suffering and we’re not getting the grants that we should to develop our ground, we’re not being allowed to move on from our past because there’s no government sitting and there’s nothing we can do about it,” she said.

When Róisín passes the barracks daily on her way to and from work, all it does is remind her of the daily intimidation that she experienced at the hands of the British soldiers stationed in the area during her childhood. Born at the start of the Troubles she has lived under the gloom of the barracks her entire life.

Another person affected by what this building embodies is club legend Oisín McConville. He too experienced the persecution and tyranny of the forces based in the town.

“A Lot of people still suffer to this day because they grew up not thinking that what was going on around them was affecting them,” said Oisín.

“During the Troubles bombings shootings and killings were commonplace, you always felt like you were in the line of fire, it doesn’t matter if you’re catholic or protestant, soldier or policeman, everyone has been affected by it,” he said.

Oisín now works as an addiction counsellor helping people who continue to suffer the mental health effects of the now ceased violent conflict. A victim himself, his life’s work is to help people overcome the deep internal scars that have remained raw such has been the failure of the state’s dealing with its legacy in Northern Ireland.

“When you look around Europe, the north of Ireland is struggling more than any place else when it comes to addiction and mental health and if we can pinpoint things then we can try to source help for people,” he said.

It was reported by mentalhealth.org.uk that 70% of adults in Northern Ireland have experienced mental health issues in the past year. This is compared with just 18% in the Republic. The driving factors behind this are the legacy of the violence, how it has been dealt with on a governmental level and the resulting high levels of economic deprivation.

This huge issue in Northern Ireland has only been worsened without a functioning executive. The heightened levels of fear and anxiety caused by the uncertainty of Brexit particularly regarding the border issue have exacerbated this even further.

Oisín has recently overcome his own struggles with the legacy of the violent conflict. Much like many others who grew up during it, he did not think that the horrific challenges of everyday life under occupation were affecting him. Hidden beneath an illustrious playing career Oisín suffered from a gambling addiction for many years.

A habit that started as a harmless one as a teenager but later became the only place where he felt at home. Gambling free now for almost 20 years Oisín aims to spread awareness of the struggle he faced through his notoriety and bravery in telling his story as well as in his line of work.

“The way that this legacy trauma manifests itself through drinking, gambling, and drug use and so we need to have awareness that an addict isn’t just an addict, it’s because of what they’ve seen and what they’ve experienced as they were kids,” said Oisín.

Northern Ireland has yet to deal with the effects of its past. Brexit has made this all the more difficult. Since 1998 huge work has been done under the peace process but many feel that much of this has been reversed and hampered by Brexit.

Alex Wimberly is the leader of the Corymeela Community, Northern Ireland’s oldest peace and reconciliation society. He sees the effects every day with the people that he works with in their headquarters in Ballycastle.

“Before Brexit, there was a landscape where we were all able to have conversations that were less threatening because the 1998 Good Friday Agreement was underpinned by this idea of European commonality,” said Alex.

“Brexit has caused people to return to the questions of whether you are British or Irish, as opposed to European whereas before there was the promise of being both rather than one or the other,” he said. “Now that’s a thing of the past and the concept of winners and losers has been reintroduced.”

Post-conflict the EU was a key player in the peace process. It aimed to build reconciliation on common economic interests. This allowed for the two political extremes of Sinn Féin and the DUP to work together in government.

With this foundation now collapsed along with the power-sharing institutions Northern Ireland has now reverted back to its divisive politics of green and orange. Brexit has been the spark to reignite this fuse, the Irish Sea border proving too much for the DUP to share power any longer.

The lack of government directly affects the quality of work that can be done by reconciliation centres such as Corymeela. The issue of funding, much like the issues faced in places like Crossmaglen and Long Kesh hand-ties the communities facing an already uphill task in trying to knit the fabric of Northern Ireland’s frayed society back together.

“The way that politics has malfunctioned in Northern Ireland means that we don’t have the continuity of funding that we need to operate in the manner should,” said Alex. “The funding that we do get is often very sporadic and whether it’s successful or not it will come to an end after two or three years.”

“That means that the work that we do becomes very targeted and objective-based rather than the actual work that we need to do which is building sustainable relationships and communities,” he said.

The current make-up of the polarised post-Brexit political geography has also contributed to the work of peace-building. Northern Ireland is a society splintered on every facet, even when it comes to building a better future together

“Since Brexit, the peace process itself has often become politicised because we have two parties representing the two sides, funding then becomes politicised as a result and everything is made harder,” he said.

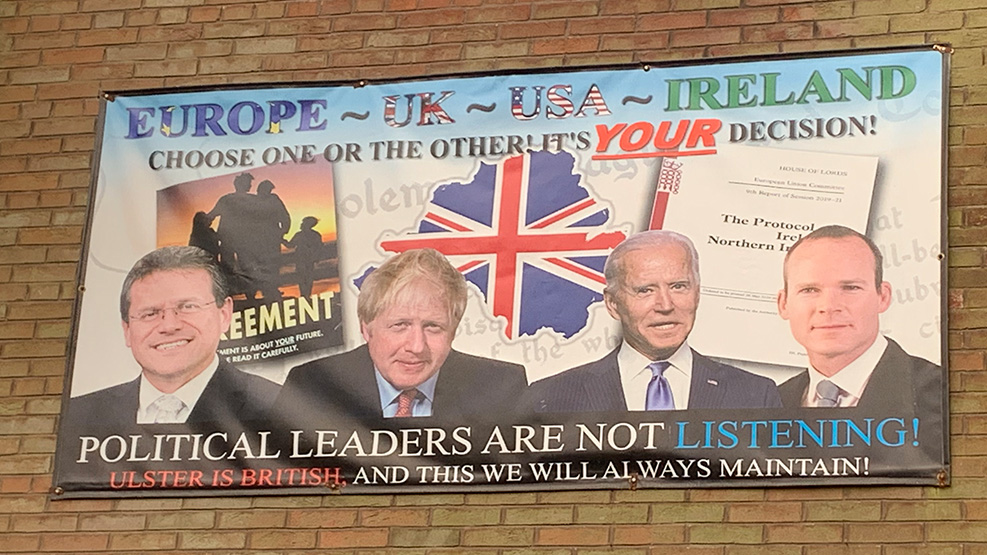

The politically charged atmosphere in Northern Ireland is in contrast to the relative peace before Brexit. There is an almost palpable sense of tension passing through in particular loyalist communities. The Irish Sea border has caused many to feel cut off and isolated from the rest of the UK.

“The loyalist community feels very much abandoned by Westminster and feels as if the walls are closing in on them,” Alex explained. “What they see as essential to their identity, even to name that as something to be concerned about is not a conversation that many people want to or can have politically because it raises the anxiety levels so much.”

Martin Snodden is a former loyalist paramilitary prisoner of Long Kesh. Since his release, he has been working in the area of conflict mediation and the peace process. He has seen and understands better than anyone how Brexit has affected inter-community relations and people within his community.

“Brexit was like an asteroid hitting the peace process,” said Martin. “The unionist community didn’t vote for the Irish Protocol and it’s because the southern government used the excuse that if there was a hard land border there would be a return to violence as leverage.”

“The Irish government and the EU were hugely supportive in bringing about peace here but many people would argue that they’ve actually shelved the Good Friday Agreement and tore it up as a result of the Protocol.”

This feeling of abandonment can be seen in loyalist areas where anti-protocol signs have been erected alongside the Union Jack’s and protestant Orange Order flags. Many feel failed and cheated by the outcome of Brexit not only by the EU and Irish governments but by the DUP and British government who promised a strengthened union pre-Brexit.

“The word betrayal in red capital letters is how many in the unionist community feel, a great wound has opened again, and trust is now something of the past,” said Martin.

The issues to the peace process caused by Brexit have been sheer. But the broader issue of the violent conflict and its legacy continues to bubble beneath the surface in Northern Ireland.

Belfast remains a divided city where civil disobedience and rioting happens routinely. It’s still so clear to sea with each neighbourhood and street hoisting their colours, marking their territory and their allegiances.

“Legacy is the single biggest issue not just in Northern Ireland but in Ireland as a whole,” said Martin. “We’ve never reconciled our past and that is what we need to focus our attention on so that we can create a more positive future.”

Martin sees an obvious solution to help tackle the stem of many of the issues affecting Northern Ireland. However, in order to do so it requires a functional progressive-thinking government to deliver it.

“I see Irish history as a tool to create reconciliation, we need to have an awareness of the different perspectives and multiple truths that support the narratives that have been created to support desired political outcomes.”

“To do that we need a neutral state education system without any interference from the church that would teach everyone the same thing for the benefit of the future of our society,” he said. “We need to teach in line with the Irish flag, acknowledge the green and the orange but focus on the white and that is everything that’s in between.”

Dealing with and interrogating the past is something that Northern Ireland has failed to do.

Dr. Thomas Leahy from Cardiff University is an expert in Irish history and politics. He has done much work with regard to the legacy of the conflict and has recently spoken to the Irish parliament about the ongoing issues surrounding it.

An alarming recent development from the British government is representative of how poorly the past has been dealt with across Northern Ireland.

“Quite sneakily during COVID in 2021 Boris Johnson’s government passed a Statute of limitations bill which gives unconditional amnesty for anyone involved in the conflict,” said Dr. Leahy.

“The British government unilaterally scrapped the agreement made with all other participants of the peace process by giving this amnesty and it’s illegal under international law,” he said.

The hap-hazard nature that the British government has thought up this bill is reflective of how messy the legacy process has been. If successful it will mean that no further convictions can be made holding victims of the conflict hostage by never allowing them closure justice.

It also further highlights the influence and impact, be it for better or worse, that decisions made in London can have over the lives of people living in Belfast, Crossmaglen, and across Northern Ireland.

“This bill as well as everything that’s happened over Brexit and its fallout has shown that the British government has too much power over what happens in Northern Ireland,” said Dr. Leahy. “Having this unilateral ability to do things and have such an impact on people’s lives is dangerous especially when they don’t have a mandate or majority to do so.”

The failure of the government, both in Belfast and in London has meant that the peace process and conflict legacy has been a disaster. Without a functional government funding cannot be dispersed to the places that need it most in order to confine the past to history.

It also means that the proper structures cannot be put in place to allow the space for it to be understood and examined in a way that can allow closure.

Brexit has caused the total collapse of these intuitions designed to allow for these changes to be implemented and has facilitated the return of a politically charged environment pitting Catholics and protestants against each other once more. The result is that Northern Ireland remains stuck in this strange position where progress continues to be thwarted by the past.

With a failed political system it often means that ordinary people like Oisín and Róisín in Crossmaglen or Alex in Ballycastle are left to do the government’s work for them. The same is true for Martin Snodden who is part of a group called the Carson Project. It is made up of ex-combatants aiming to build inter-community relationships.

“When I take a loyalist band down to Dublin and I bring them to the republican plot in Glasnevin cemetery, they pay respect to all of the Irish dead,” said Martin. “I smile to myself because without question there’s hope for the future but it can only be navigated by good captains, if we’ve bad captains they are going to lead us into stormy seas.”

“Northern Ireland has to deal with its past and the best way to do that is through acknowledgment as opposed to criminal prosecutions, that can only come about if we learn from the past and move on from it as opposed to commemorating it,” he said.