As medical professionals begin to advise nature for their patients’ mental health, what is the impact of these so-called ‘nature prescriptions’?

As she entered her GP surgery last November, Rosie Smith-Kalmus – a 22-year-old student at the University of Glasgow – thought she’d emerge with the translucent green piece of prescription paper she was used to seeing. She had been diagnosed with generalised anxiety and an acute panic disorder over three years before.

“It was getting to a point where I was often scared to go outside, because I was scared of having a panic attack,” she says. “Panic attacks are a really physical thing […] my stomach gets really sore, really tight and really uncomfortable. My joints start to feel stiff; my mouth goes dry.”

This wasn’t her first-time seeking help, nor was it her first prescription. The low dose of beta-blockers failed to stop her anxiety simmering consistently throughout her daily life. Introducing anti-depressants had helped, but months later, she still felt overwhelmed.

Leaving the doctor’s that day, she did have that recognisable green slip in hand, but this time it came with the addition of the words ‘Pinkston Waterpark’ scrawled on the back, with the recommendation to go there to open water swim rather than an inside pool.

“[My GP] kept asking me what kind of sports I do. I do go to the gym, but my mental health being improved by exercise has never really been true for me. I said I swam as a kid, so he was like ‘right, wild swimming.’”

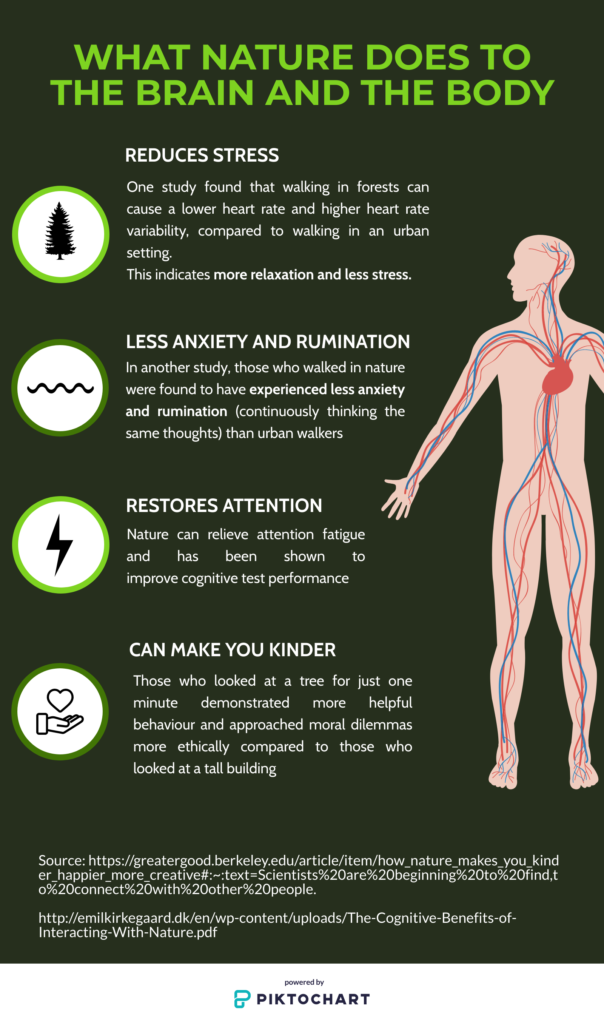

Wild swimming has its own particular benefits, such as research from the National Library of Medicine in the US suggesting cold water can have an anti-depressive effect. But numerous studies laud the mental health benefits of interacting with nature in general.

In 2018, a study led by neuroscientist Dr Andrea Michelli found that the mental health benefits of going for a walk can last for up to seven hours. Australian researchers found in 2016 that just 30 minutes spent outdoors per week can reduce depression. In a survey conducted by mental health charity Mind, it was found that 94% of people involved in ‘green exercise activities’ said that their mental health had benefited.

One of the leading advocates for nature-based approaches is Dr. William Bird, a GP in Reading and the CEO of Intelligent Health who has shown his support for over two decades. Setting up the first Green Gym in the 1990s, where people could exercise outside through sowing seeds, creating wildlife ponds and planting trees, Dr Bird has long been confident in nature’s ability to improve our mental health.

“When you go out into nature, the eyes look around and you suddenly see that everything you have been programmed as a hunter-gatherer to want to be safe, is there. You’ve got trees, you’ve got grass, you’ve got shelter, you’ve got water, you’ve got food… so your brain has been programmed to want that. So suddenly, you feel safer to where you are.

“Rather than being an isolated little blob trying to deal with the world which is out there” – he gestures outside of the confines of the webcam frame – “which is ‘hostile and horrible, nature says actually, the world out there is absolutely beautiful.”

When out in nature – whether that’s plunging into sub-temperatures on her outdoor swims, walking her dog Luna, or during her challenging cycles around the fields in her childhood hometown – Rosie feels the physical symptoms of her anxiety dissipate. “Calming down the physical symptoms really helps to stop my brain from speeding up and creating more panic.”

It’s unclear how long doctors like Rosie’s have been informally suggesting this interaction with nature to their patients. But in October 2018, nature began to be formally prescribed by GPs in the Shetland Islands after a successful trial run by NHS and the RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds). The project was the first time that nature has been formally prescribed in this way.

While it may not be a prescription you can take to the pharmacy, it’s one that Shetland Islands Manager for the RSPB Helen Moncrieff firmly believes in: “We thought one thing that connects everybody is the natural world and health. And there is evidence that nature can improve health and wellbeing.”

The prescriptions during the project came in the form of two resources: a leaflet with evidence, information and advice for activities and suggestions, and a calendar of monthly ideas and events. A doctor could circle a length of walk or direct them to a particular activity, such as drawing a snowdrop, most appropriate for the patient. The calendar spans the whole year, with lists including ‘planting some bulbs’ in February, ‘making a meal with the flower of a dandelion’ in July and ‘go otter watching’ in November.

“That’s really how simple it is,” Moncrieff says from her home in the Islands. “It’s a little nudge to get outside.”

While we associate a walk in the park with being easy, for those suffering with depression it can be a struggle to even get out of the front door. “I would literally just leave the house for doctor’s appointments,” says Frankie, a supermarket assistant from Portsmouth, referring to her severe depression during the second year of university.

In her first visit to the GP, after prescribing her anti-depressants, her doctor told her to go outside and go to the park. The sentiment was later echoed by other doctors.

“There were three different doctors who have all talked about being outside as like some kind of magic cure, and I feel like anyone who’s ever been seriously depressed will tell you that you can’t even leave your house at the best of times, let alone chill in the park. It’s not going to make you just magically better.”

To avoid minimising an individual’s mental health struggles in this way, Dr Bird says a doctor needs to gauge where patient is. “Wild swimming is fantastic, but if someone is in a place where they’ve just started to look at a David Attenborough programme and that’s as far as they’ve got, that would be the scariest thing in the world.

“What we tend to forget, particularly environmentalists, is that we impose our values about what we feel is good for someone, on people who are in a very different place. And we are very bad at being sensitive to people’s needs.”

Another challenge for prescriptions is location: increasing urbanisation means that the coastal paths of the Shetland Islands and other vast green spaces are the exceptions, not the rule. A 2018 study by Ambius found that 40% of British office workers spend a maximum of just 15 minutes outside per day, excluding their commute to work. 22% only spend only 30 minutes.

Despite the urban population of the UK being estimated at 83.4% in 2018, Dr Bird assures that the mental health benefits are not exclusively reserved for those with an abundance of nature on their doorstep.

“I’ve often said for people in the middle of London, you just go to a tiny, mini, park where you can sit down under a tree. […] It doesn’t have to be a big park, it doesn’t have to be wild nature, it doesn’t have to be anything.”

Moncrieff agrees that adaptability is key: “What works in Shetland isn’t going to necessarily work in a city. But nature should work with everybody.”

The importance of accessibility is one of the reasons why the RSPB is doing another trial in NHS Lothian, which covers more urban areas of Scotland, like Edinburgh. “People have the same health problems everywhere that they do in the Shetlands, be it physical or mental health, so [that differing access means] we have to nudge people out a bit more.”

This nudge seems to be needed. One study led by academics in England, Australia and New Zealand found that living in urban areas, in combination with increasingly busy modern lifestyles, may be causing a decline in interactions with the natural world.

Still, even improved availability and a helpful nudge won’t always be greeted with open arms, no matter the patients’ location. Medication is still the most commonly-prescribed treatment for mental health problems – according to the NHS, 70.9 million prescriptions for antidepressants were given out in 2018. Dr Bird says he has been met with resistance from patients when trying to advise nature as a treatment. “The patient feels they’re being short-changed. They say ‘look, I’ve come to a doctor, I want expensive drugs, I want something special because you’re a specialist doctor, so I want special treatment for special things.’”

“Some of them say, ‘my granny could’ve told me that.’”

Rosie says antidepressants changed her life, and that her doctor prescribed nature as an additional treatment rather than as a replacement: “He was like: ‘Okay we’re gonna increase your antidepressant dose anyway but this is something to do alongside.’ And he said, ‘if that doesn’t work, we can try out different options.’”

Moncrieff acknowledges the importance of nature prescriptions not being posited as a replacement of traditional medicine, saying that they can be for low-level mental health problems before people are needing prescriptions, or used alongside traditional medicine. She adds that during the NHS/RSPB trial, a doctor would offer the options of medication or a nature prescription. If the latter helped, then that was that, and if not, the patient would then get medicine.

She believes that the future of nature prescriptions is bright, but uncertain: “This is a viable option to complement the more traditional medicine,” she says. And the global interest is evident, with not only national newspapers reporting on the project, but international organisations too. “We’ve had journalists and people from all over the world getting in touch – from Aboriginal groups in Australia to a Danish stress committee.

“But because it’s still new, we will need to learn.”

The questions the RSPB are still seeking to answer include: Is a more outdoor-inclined GP more likely to prescribe nature? Are there certain conditions that a GP is more likely to prescribe nature for? Moncrieff says that these were set to be explored during the project in NHS Lothian, but it has been put on pause due to Covid-19.

Dr Bird agrees it will take some time before nature prescriptions become part of the fabric of the UK healthcare system, not only because there are unanswered questions but because of public attitude towards this non-drug approach to mental health. But in his experience in advocating for the benefits of walking, it’s only a matter of time.

“When I started off, I just started by promoting physical activity and walking, and walking at the time in the 1990s was completely uncool.” Dr Bird smiles. From being something ‘uncool’, walking is now seen as a mainstay in a healthy lifestyle, with walking charity Ramblers saying that 97% of adults now believe that the public should be encouraged to walk more for improved health.

It’s only a matter of time before attitudes towards nature catch up, he says: “We know that nature’s really good. So, we’ve won that argument, the evidence is there.

“We just haven’t quite sold it to the public yet.”