St. Pauli are the first and only football club whose emblem has been added to a counter-terrorism policing guide by the U.K government. What does this mean for the British fans who support the club?

It could have been the deafening atmosphere inside the Millerntor Stadium, with ACDC’s ‘Hell’s Bells’ blasting through the speakers before kick-off. It could’ve been the scuzzy, gritty feel of the stands, the faint smell of beer and marijuana or the bizarre blend of punks, anarchists, tourists and sex workers. But something about St. Pauli gripped Robert Murtagh enough that before long, a visit to Hamburg turned into a 12-hour bus journey with the supporters down to Nuremburg.

“We went on a fan coach and we just felt completely integrated,” he says. “A few lads from Ireland on this coach with hardcore St. Pauli fans and we were just treated as part of the fanbase. And that’s what the club represents, a feeling of openness and friendliness.”

Now 24 years old and living in Belfast, Robert has followed the club for the last three years. St. Pauli are an alternative for many fans based in Britain and Ireland based on feelings of inclusion, tolerance and identity.

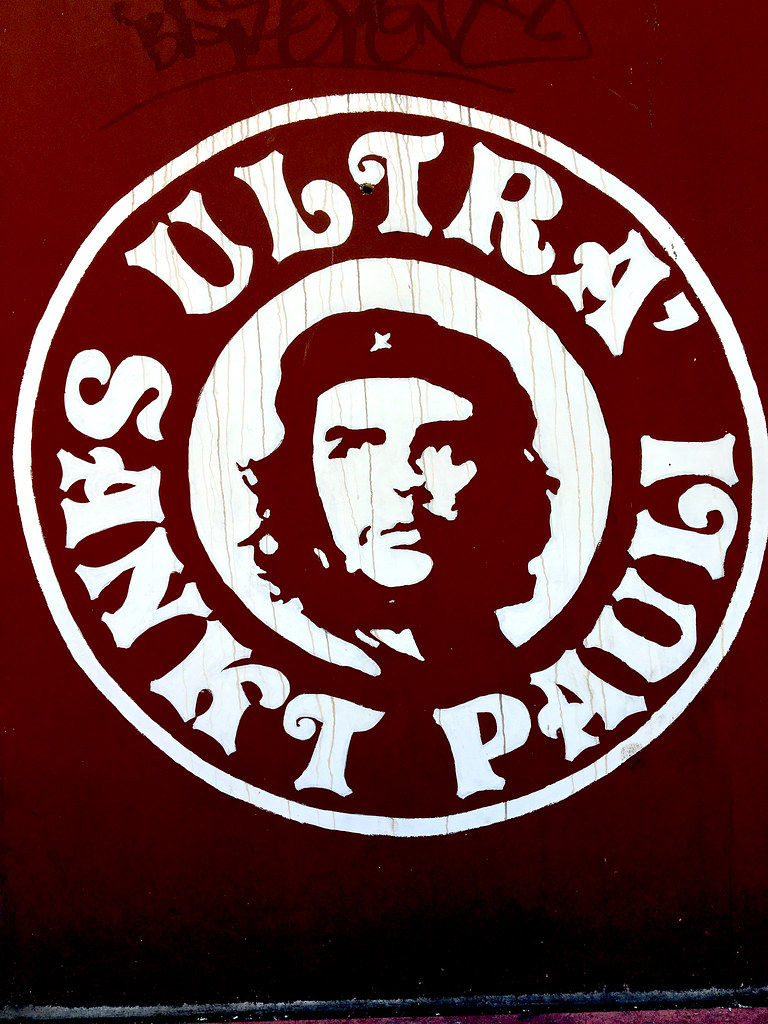

The club are one of the most openly left-wing football clubs on the planet. One of the first teams to make public demonstrations against all forms of discrimination and their unofficial logo, the skull and crossbones, or Totenkopf has been adopted by the club as a symbol of their rebel status in the face of modern football.

The logo is a sight to behold and has been all things, from an ironic joke, to a commercial tool and a symbol of political rebellion. As the players walk out onto the pitch at the Millerntor, often their first points of focus are the green grass, the towering, rickety floodlights, then the sea of black hoodies and intimidating white skulls.

But a landmark case has set an awkward precedent for the club and its British fans. In January 2020, the U.K government added this unofficial Jolly Rodger crest to a counter-terrorism symbols guideline. Alongside the swastika and other neo-Nazi imagery.

Already a club like no other, St. Pauli are the first and indeed only club to exist on such a list. It was discovered by The Guardian and also contains the logos of Antifa, Green Peace and PETA, among other socialist groups and factions. The move caused a mix of bemusement, exasperation and anger.

“I’ll be honest and say it made me laugh, but it also made me angry,” Robert says. “The symbol signifies our resistance to corporate football where fans, players and stadiums as commodities and assets rather than important aspects of social cohesion.”

One of the punks who was a focal point in the politicisation of St. Pauli, Sven Brux now works for the club. He covers the history of the club for their official website, which notes that as St. Pauli became a place for defectors of other clubs.

During the mid-1980’s, the team and the area became more synonymous for left-wing fandom and activism against local issues. The logo started to emerge at the Millerntor, worn by a group called the ‘Black Block’, who initially aimed to show public solidarity with squatters in the increasingly gentrified district.

“The message, then, was ‘Poor against rich. Workers against bosses,” Brux writes on the club website. “”The skull and crossbones has become a symbol of the fans of the St. Pauli Football Club – if not of the club as a whole – that is known throughout the length and breadth of Germany. Leaving value judgments out of account, its history has been one of appropriation and commercialisation which tends to occur only in the worlds of music or fashion.”

The Totenkopf can be seen in all corners of the U.K, but the level of actual fandom varies. There are fans like Robert Murtagh who have made the pilgrimage to watch the team, or those with a loose connection to the club, based on shared political ideals and music taste. It prompted many to take to Twitter after the symbol appeared on a government document to ask, “I wear this symbol every day, am I a terrorist?”

But in typical St. Pauli fashion, many fans across the U.K actively protested. As the Hamburg-based supporters are no strangers to protest, whether it be through the pen or the sword, the Glasgow St. Pauli fan group wrote an open letter questioning the rationale and the effect the document may have on their own fandom.

“As a fan club our initial reaction was one of incredulity at the absurdity of this situation,” their letter says. “However, this has given way to concern and anger that the social values which are promoted by the club and adopted by our fan club have been considered in any way to be extremist. These values are universal and should be promoted and lauded, not regarded as a threat.”

The letter was picked up by Glasgow North MP Patrick Grady, who addressed Home Secretary Priti Patel, noting St. Pauli’s shared values of inclusion and support for those discriminated against, as well as the thousands raised by the group for various refugee charities.

Other British St. Pauli groups echoed the sentiments. But perhaps the most poignant was James Lawrence, St. Pauli’s Welsh central defender taking to Instagram to publicly question the decision. He claimed the club’s values continued to make him proud to play for the club, despite the ruling, finishing with “Anti-Fascist, Anti-Racist, Anti-Sexist, Anti-Homophobic. What’s not to like!”

The list raised many eyebrows due to the multitude of different groups listed. A sizeable chunk of the backlash also came from the inclusion of Extinction Rebellion in the backdrop of climate change protests taking place at the end of 2019. But while these groups can see thousands of members attend one-off demonstrations, questions remain over the effects this list will have on the small groups of St. Pauli fans dotted around the country.

“I think it’s the first step in trying to criminalise anti-fascism in the U.K,” Robert says. “We will continue to stand for the values we believe in. Symbols are important but actions are what change things.”

What Murtagh says is very akin to the values St. Pauli abide by. Back in Hamburg, the Totenkopf is an ever-present symbol, not just in the stadium on match-day, but throughout the district. Despite starting as something of a joke, its symbology is evident too.

During games, a ‘No Football for Fascists’ sign is hoisted. The stands host one of the more eclectic audiences, with the ground being yards away from one of Europe’s most notorious red-light districts. The punk vibe is upheld through banners, smoke bombs and pyrotechnics and the speakers blast raucous, head-banging anthems to welcome the team out.

For the bemused, it may be a case of wearing the Totenkopf logo and half-jokingly worrying if they will be tailed by an undercover government vehicle. For those who embody St. Pauli’s spirit of resistance, the logo may now be a badge of honour.

“I don’t think it will make any difference to how we as St. Pauli fans try to stay true to the values of solidarity, community, resistance, equality and justice,” Robert says.

Away from the mix of laughs and anger, others worry what sort of precedent this could set moving forward. William Magee, a sport and politics journalist at The I fears the criminalization of not just the symbol, but those who follow the club for political reasons.

“It’s worth noting that the material itself lists ‘St Pauli Football Club’ among its Left-Wing Signs and Symbols Aid, not just the Totenkopf,” he says. “So presumably any iconography associated with the club falls under the same suspicion in the eyes of the authorities.

While the decision to include the logo on such a list was a not just a confusing decision to Magee, but one that he believes may not actually act as much of a barometer to measure political belief.

“Given how popular St Pauli’s ‘brand’ has become – ironically, given their left-wing stance – the chances are that there are a significant number of people who wear their merch more as a fashion statement than anything,” he says.

If any publicity is good publicity, then it is worth reflecting on how far the logo has come since the mid-1980’s. From the days of the ‘Black Block’ waving the logo on a flag to reflect the rebellious squatters and Hamburg’s old associations of piracy. The logo, then adopted by the club. They sold then re-bought the image rights and it now acts as one of their key revenue streams.

For Robert Murtagh, St. Pauli were a club where he could find no such equivalent. When he sees the skull and crossbones, he instantly associates it with the club, a visual representation of counterculture and the values he himself professes.

“As a socialist, my views aren’t just confined to the political arena. Being a socialist is about how you live your life and how you stay true to your values,” he says. “It’s not always possible, but I try my best. Finding a football club that embodies those ideals is rare and that should be supported.”

A prominent concern for Murtagh is the list equating the far-left and the far-right. As he critiques the government’s handling of the migrant crisis and the Windrush scandal, he suggests the guidelines in general are a distraction tactic.

A similar concern is picked up by Mark Doidge, a lecturer and prominent member of the Brighton St. Pauli fan group. Speaking in February shortly after the attacks on a shisha bar in Hanau, Germany, he wonders if the government has missed the point with such a guideline.

“In Germany we had someone far-right go and kill people in a shisha bar, we’ve had someone enter a mosque and kill the Imam. This is the government not taking this issue seriously,” he says. “And by putting a symbol of a fan group or a football club from Germany shows that they really have not understood the issue.”

Counter Terrorism Policing were keen to point out the list did not expressly say all those listed were terrorists. Rather, as part of the Prevent Scheme the list was a guideline to help police and other officers to “identify and understand signs and symbols they may encounter in their day-to-day working lives.”

Responding to the article published in The Guardian, commander at the Metropolitan Police, Dean Haydon said “The guidance document in question explicably states that many of the groups included are not of counter terrorism interest, and that membership of them does not indicate criminality of any kind.”

Would criminalising the logo have a detrimental effect on how often it is seen on t-shirts, hoodies and flags? The links to music, fashion, politics and football make it a widely sold emblem and their image is a large factor behind St. Pauli enjoying considerably higher attendances than many of their counterparts in the German Bundesliga 2.

But the meaning behind the logo means it is very unlikely it will become any less of a badge of honour for most fans. As a symbol of the club’s rebellious nature, home of the lefty, the punk and the rascal, the logo is not so much an image of sneaking around and skulduggery, but loud, proud, in-your-face resistance.

For Robert, political values are something that are carried into all aspects of life. But when he realised three years ago that he could combine this with his passion for football, it was always going to be a match made in Heaven. The badge is not baggage to him, rather, a clear message of what he stands for.

“I wear the logo with pride because of what it represents, and I’ll continue to do that,” he says. “The club is unashamedly anti-fascist, pro-LGBTQ, pro-women and pro-refugee, at the core of the club is solidarity.”

Throughout the conversation, Murtagh speaks of solidarity frequently. It may have connotations politically, socially and culturally, but it may also speak volumes about the solidarity he felt when he was welcomed on the supporters’ coach three years ago as one of them.

“Solidarity isn’t a noun, but a verb,” he says. “It requires action and football clubs are in a great position to facilitate it.”