Actors and musicians face the UK’s highest suicide risk. With debt, rejection and instability piling up, how long can young performers survive in the industry?

Behind the scenes, many actors, especially those just starting, are quietly fighting a mental health crisis. Glitzy costumes and unwavering grins are only a small part of this career. For Jess Dixon, 22, a recent postgraduate in Musical Theatre, life off-stage is the definition of ‘suffering for one’s art’; it’s financially draining, mentally overwhelming and anxiety-inducing.

“Finding work is really stressful,” she says. Dixon is fresh off a series of productions and is about to stage manage another, all while preparing self-tapes for continuous job applications. She’s on Spotlight, the leading casting platform for UK performers, but without an agent, her opportunities are limited. “You can’t see everything if you don’t have an agent. Big productions like Mean Girls or Freaky Friday were recruiting actors recently, but they are practically off-limits. It feels like you’re invisible.”

Her experience reflects a broader issue. Despite having talent, training, and resilience, early-career performers often find themselves applying for numerous roles, hearing nothing back, and trying to stay financially afloat in a volatile industry. “Jobs are few and far between. Instagram and social media do help, but there’s never any guarantee of a job,” Dixon says.

Unemployment often accompanies financial pressures. With the extortionate fees of drama schools, courses, and training, they have become inaccessible to most. Dixon has faced numerous moments of financial strain, but at what cost? “I’ve had so much stress in the past year of paying for this course from my own pocket because master’s loans don’t cover it and accommodation is ludicrous,” she says, “I have had to do teaching whilst doing my master’s, which has brought its own complications with rehearsals and shows.”

Post-university, Dixon plans to return to her minimum-wage job at Pizza Express. She prepares herself to face the reality of the oversaturated and underfunded industry. Continuing her job as a part-time drama teacher, the strain of working two jobs while auditioning for what is often a dead-end opportunity categorises the industry as out of reach for many. It certainly requires a high level of resilience.

And then there’s the emotional toll. Dixon was part of 20 Bridges, a physical theatre production exploring the lives of those who died by accident on the Thames. She played a Victorian woman in love. In a nutshell, the plot is overwrought by grief, suicide, and isolation. The impact of this role wasn’t just physical. “It’s heavy without you even realising. You start saying things like, ‘let’s just run that death scene again.’ You become desensitised.”

The pressure built silently. Rehearsals intensified, and two shows were piled on top of 20 bridges, alongside producing self-tapes and line learning. All the while, Jess was quietly coping with grief in her personal life. She very sadly lost her grandmother before her crucial end-of-year exams. Rehearsals continued. The pace of the industry doesn’t stop to allow emotions to run high. “I thought I’d be worse than I was, but I don’t show my emotions. I just cried once, had a panic attack, and went back to rehearsal.”

Emotionally intense roles offer catharsis, but when actors are also carrying personal grief, the lines between character and self can blur. “Because my course was so small, we didn’t go off stage. Not even for a breather. You’re in that world constantly for an hour and a half. There was no escape from the heaviness.”

The list of an actor’s external pressures continues as Dixon also speaks to the emotional challenges of performing in a competitive environment where external validation is rare. “Not getting validation is really hard. Even in my course, when one person got all the praise and no one else did, it was so difficult.” She says, “There’s always a drama school teacher’s favourite. And when those teachers are industry professionals, you start to wonder, Is this what the real world will be like? It really knocks your confidence.”

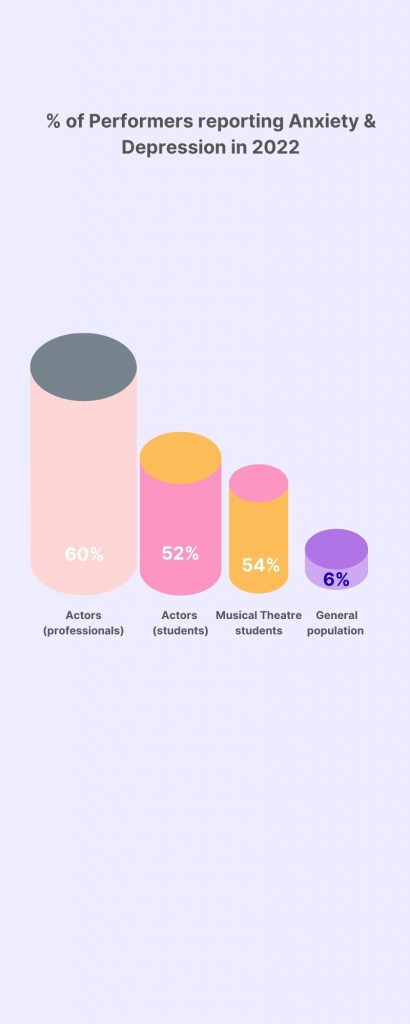

The constant feeling of inadequacy and self-doubt appears to be a universal experience within the industry. According to a scoping review by Equity, the UK’s only performing arts and entertainment trade union, 60% of actors report having symptoms of anxiety. On top of that, 54% of musical theatre students report a level of depression or anxiety that meets the rate for diagnosis of a mental disorder.

Dixon brackets within that 54%. Whilst nothing compares to her passion for theatre, constant anxiety is her reality. Jess describes the moments before the curtain as charged with nervous energy. “Performance nights are full of adrenaline,” she explains. “I was mostly distracted by the pre-set, but when you hear the audience entering the building, you definitely feel anxious.” For that particular role, though, she had no choice but to push through. “My character wasn’t someone who would’ve been jittery, so I had to shake it off and go on.”

Equity listed several contributing factors, including job precarity, such as erratic and short-term employment, low pay, and work over- and underload. Part of this statistic also comes from exposure to regular performance. The stress from this may stem not only from others’ opinions but also from competition and comparison with others. Dixon is just one of many paying the price of becoming an artist.

Sam Bailey, 22, another young actor trying to break into the industry, shares a similar sense of burnout. “There’s always that pressure to work, to get your break, but also to survive. I took a zero-hour contract so I could drop everything for an audition. But that means sometimes I only get four shifts a month.”

Bailey is currently chasing three different employers for outstanding income from acting work. The total he’s still owed amounts to £300. “I work in the theatre building sets, but the venue closes in August, so I don’t have any income for the foreseeable future, which means the little I have has to stretch through the month. There are moments like this where it feels like a career in the arts is just a dead end”. For Bailey, that missing £300 would just about keep him afloat.

Since leaving university, the pressures of the real world have deeply affected Bailey’s ability to cope by himself. Financial instability creates a loop of anxiety and self-doubt. He says,” I’ve had to go into therapy and start taking SSRIs. I’ve been swept through the process of OCD, depression and anxiety because I’m sitting in this little room in my parents’ house applying for things and just failing.”

The never-ending cycle of negative self-talk makes him question his talent and achievements. He says, “The only thing I have to rely on is my university grades to validate my talent.” He describes the difference between the educational setting and the professional industry as brutal. It can emulate thoughts of giving up, “There is an unbelievable level of self-esteem needed for this industry, which is so challenging. You have to be prepared to get beaten down. Sometimes I think about doing something more stable, like teaching. It’s definitely crossed my mind more than once.”

What adds to the emotional weight, Bailey says, is how personal the rejection feels. “There aren’t many other industries where rejection is the standard. You’re constantly putting yourself out there, going to auditions and hearing nothing back. There is only so much constant rejection you can take”

For Bailey, identity isn’t a costume. He was shocked at how much rejection he had faced due to his outward appearance. He takes pride in his association with what he calls ‘the alt community’. His long hair, eyeliner, and bond with alternative culture are deeply personal. It is deeper than just a fashion statement; it’s a way of expressing himself outwardly. After multiple requests from casting directors for him to change his appearance, Sam feels that he must consider how vital his identity is to him. “It’s hard to weigh up: Is it worth trading out my self-identity for something that’s going to earn me some money? Upon reflection, I am disappointed that I have considered that. It’s sad that changing myself entirely can be labelled with a pound sign.”

This internal conflict isn’t limited to those still trying to make it. Some performers, like Natalia Foster, have stepped away entirely. Despite a childhood passion for theatre, she pursued a degree in psychology instead. “I unfortunately thought theatre would never be a viable career,” she says. “You don’t know where your next paycheck is coming from.”

Foster also faced family pressure. “I come from a very STEM-heavy family. The idea of doing drama was absurd to them. I did well in science, so I thought I’d better do something that guarantees a career. But it’s really sad, because I do love theatre.”

Scared of what Foster is currently facing, what finally pushed her away was the industry’s fixation on looks. “You could be the most talented person in the world, but if you don’t look the way they want, you’re invisible.”

In an article published by The Actors Centre in 2025, a UK-based charity that has provided professional development and support for actors for decades, the organisation continues to place an emphasis on actor training to support the mental health of performers. They claim that many actors leave the profession within the first five years after graduation due to the industry’s precarity.

Unfortunately, this is the current way of the industry. Graham Saunders has taught Drama and Theatre Arts at the University of Birmingham for 25 years. “I think the precarity of the acting profession, always having to prove yourself, the lack of agency in work, and favouritism with particular casting agents are mentally straining.” He describes the acting career as having an expiration date. “The main thing is the anxiety of getting that big break, and at what point do you decide you’re not going to pursue that career anymore. I’m still in contact with students from over the years, and most of them no longer pursue a career in acting. There is a shelf life of how long you’ll do it until you get fed up with not earning any money. It is stressful. “

Graham Seed, 75, an experienced actor with over 55 years in the profession, remembers a different time. “Mental health was never really an issue. I did so many years of rep that you couldn’t be ill. They call it doctor theatre. You went on stage and you felt fine, you pick those issues up when you come off.” He recalls performing the night his mother died, not out of obligation, but out of deep commitment to the team: “We didn’t have understudies. You didn’t let people down.”

When Seed graduated from RADA in the late 1960s, it was still possible to make a living solely from acting. Having gone on to star in major productions like The Durrells, he reflects on just how much the industry has shifted. “You can’t do that anymore,” he says. “You have to have other skills to keep you afloat. The industry has changed.”

That change hasn’t just been financial. Seed notes that there’s now far more awareness around mental health than when he started. “At the beginning of a production, there’s often a meeting about safe spaces,” he explains. “But it’s still difficult. I know on a personal level how young people in the arts can suffer; there have been a number of suicides.”

For Silvey, 66, another seasoned professional, who has both performed and produced long-running shows like The Mousetrap, the pressures were often financial. “We had a bonus system of £3,000 if you didn’t go off. You lost £150 every time you missed a performance. I once had to go on stage after being on an antibiotic drip all morning because I couldn’t afford to lose the money.”

She reflects on how things have shifted. “Now, without that bonus, there’s rarely a week when someone doesn’t go off. Back then, you just didn’t. You never knew when your next job was coming, so you clung to what you had.”

But she also recognises the dangers of that mindset. “We had this boy in The Mousetrap, a sensational actor, but deeply unwell. He couldn’t handle the pressure or the audience. We had to tell him to step away, for his own wellbeing. He hasn’t worked since.”

Both Silvey and Seed describe an industry filled with vulnerability. “Actors are brave,” says Seed. “We go on stage and bare everything. And then we wait for the next job. That waiting can be the hardest part.”

Despite the old-school resilience both actors still carry, they acknowledge the cost. “I’ve been bullied by directors,” Seed says. “I once did a job where they were clearly hoping I’d leave so they wouldn’t have to pay me. There’s often a horrible undercurrent. But I didn’t go crying to anyone. You just put up with it.”

Silvey agrees, “You’re a freelancer. If you go off, someone else takes your role. I’ve seen directors pinned against walls by actors because the stress gets too much.” And yet, even after decades, Seed admits, “When I’m not working, I’m waiting for the phone to ring.”

The curtain may fall at the end of a show, but for many performers, the struggle continues long after the standing ovation. From underpaid acting gigs and inaccessible opportunities to identity confusion and emotional burnout, the cost of pursuing a career in the arts is still immeasurably high.

For newcomers like Bailey and Dixon, the dream hasn’t yet transformed into an unbearable nightmare, but that resilience comes with compromise, sacrifice, and constant self-questioning. For those like Natalia, it became a dream deferred. And for veterans like Seed and Silvey, the love for the craft remains, though not without acknowledging the personal toll it has taken.

“I have to keep trying and hoping someone will take me,” Dixon says. “I know I wouldn’t enjoy anything else the way I love theatre. But I definitely question if I am good enough. Is this really worth it?”