With the sea nibbling at the land every day, how are the villagers of Gobardhanpur fighting a seemingly loosing war of attrition?

At dawn, the sky above Gobardhanpur village in the G-Plot Island in the Indian Sundarbans is the color of raw clay. From the doorway of her one-room makeshift house, 45-year-old Sabitri Mondal watches the tide push closer to the embankment.

The landscape is a collage of new channels, exposed tree stumps and electric poles and ragged edges of embankment—concrete ribs, sometimes no more than a few metres wide, that try to stop the sea and fail. The air is thick with salt, the ground damp even before the water arrives. She points to the line where her courtyard once stood, a place where she used to dry fish and spread paddy on a mat. It is gone now, swallowed by the river.

“The water eats one handspan at a time,” she says, raising her palm. “Some days it takes a foot. Some days it takes a house.”

Sabitri’s story is not just her own. It is the story of thousands of families across the Indian Sundarbans, a place where the sea does not roar in sudden, dramatic waves alone. It creeps, relentlessly, silently, eroding earth from under homes, mangroves, and memories. If cyclones are the visible fists of climate change, then erosion is its quiet, grinding teeth.

The Sundarbans, spread across India and Bangladesh, is the world’s largest mangrove delta. But it is shrinking at an alarming rate. According to India’s National Centre for Coastal Research, nearly one-third of the Sundarbans’ 102 islands are under severe threat from erosion, with some—like Lohachara and Suparibhanga—already gone from the map.

Gobardhanpur village in the G-plot island, where Sabitri lives, has shrunk from 6000 bighas to 1200 bighas in the past few decades. Sagar, the most populated island in the Indian Sundarbans, is losing about 30–40 hectares of land every year.

For villagers, this isn’t just cartography. It’s their fields, their houses, their ancestors’ temples and mosques. Every year during the early monsoon, fresh cracks appear on the embankments. Mud slips into the water like sand from a broken pot. Families carry their belongings to higher ground, only to find the ground itself vanishing.

“Every year, we shift a little further inland,” says Sabitri. “But inland is finishing day by day. The sea is everywhere.”

A kilometer away, 68-year-old fisherman Nizamuddin Haque repairs his nets under a tarpaulin in Gobardhanpur. His old homestead lies 200 meters inside the river now. “I used to run to the fruit orchard on that land,” he says. “My children will never even see it.”

His story is echoed across the delta. The World Bank estimates that more than 1.5 million people in the Indian Sundarbans are at risk of permanent displacement by 2050 due to erosion and rising seas.

The family rebuilt twice, carrying bamboo poles and thatch from neighbors, before giving up on permanence. Now they live in a makeshift hut behind the embankment, with bags of clothes stacked in a corner, ready to move at short notice.

“We are living in this spot for four years, but given the speed in which the sea is coming after us, I am certain, we will have to relocate from here as well”, said Haque.

The elederly fisherman says, the sea gives respite only during the short winter months. “The sea starts eating away land from Chaitra-Baisakh(Bengali months of early summer). After our earlier land was gone, we used to live on the ‘Aila bandh’( concrete embankment made after the Aila storm of 2010). That too has gone away”, lamented Haque.

All his children and grandchildren have either migrated to Kolkata, about 100 kms north of the island, or into other parts of India as cheap migrant labourers. The elderly man and his wife survives on the land by fishing.

For villagers like Lakkhan Das, the key reason for their plight is governmental corruption, rather than changing environment.

“After the Aila Bandh fell down, in around 2018, the government immediately arranged for a tender to award the contract for the construction of a concrete embankment in our village’s sea facing side. The value of the tender was a few crore rupees. The work was completed in 2023. However, the concrete structure was unable to withstand the sea for even 1 year!”, said Das.

He alleges, there is a underwater sea current trough at the point where the land meets the sea. Adequate measures were required to prevent the collapse of the sea embankment. “The government knew about this problem, as we informed the G-Plot Panchayat time and again. Still they went on with the construction, and this collapse was bound to happen”, he said.

According to the small-scale fisherman, the government went on with the construction to ensure the ruling party of the state gets ‘cut-money’ or their cut from the contract awarded to build the embankment.

Samir Jana is the Member of Legislative Assembly or MLA from Patharpratima, the constituency under which the entire G-plot island falls. He belongs to the Trinamool Congress, the current ruling party of West Bengal.

Refuting all the allegations made against his government and party, the lawmaker said, “the central government doesn’t provide any funds to build sea embankments in this region. Yet our government arranged the money through World Bank funds and is constructing permanent embankments on a contingency basis”.

According to Jana, the rise in sea level is resulting in increased wave pressure from the sea. “If a small crack emerges, water oozes through it and destroys the entire structure. The earlier embankment was unable to withstand this pressure and was flooded away into the sea within a year. I have already started the work to rebuild the embankment in this area”.

Government sources tell, The Aila embankment in nearby Khirodnagar is also indented. A 800 metre long embankment is coming up in it’s place. In other places like Chuimuri and Gopalnagar, a 1200 metre and 600 metre long concrete embankment is coming up.

Speaking about his plans to save Gobardhanpur village, Jana said, “we are evacuating people from the conflict line. Our plan is to create a 1200 metre long embankment to save the hamlet. To create a stable foundation for the structure, we have retreated about 100 meters into the village to built it”.

The MLA stresses that it is the only possible option to save the village.

Arup Santra is a small trader in the nearby town of Patharpratima. Everyday he travels from Buraburir Tat village in the G-plot to Patharpratima by changing two diesel powered wooden ferry. He fears if the government fails to save Gobardhanpur, his village will be the next in the line.

“If G-plot vanishes, the sea will come next for our village BuroBurir Tat”, said the trader.

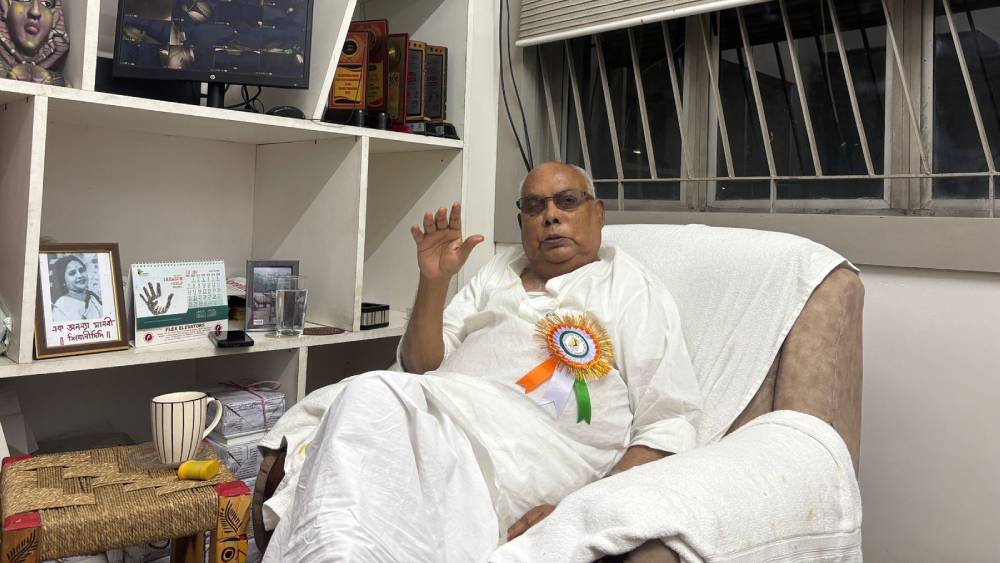

Kanti Ganguly headed the Sundarban Development Department for 10 years before his party, the Communist Party of India(Marxist) or CPI(M) was voted out of power in 2011 by the TMC. Regarded by many as one of the key architects of the development of the Sundarbans, the veteran politician stresses that mismanagement and fund syphoning by the TMC government is one of the major reasons behind the plight of the people of the Sundarbans.

Sitting at his office in Mukundapur, a suburb of Kolkata, which incidentally was a part of the Sundarban’s a hundred year ago, Ganguly said, “The Sundarbans have 3500 km long embankment. The Aila storm of 2009 destroyed around 1500 kms of those embankments. After that, we took initiative and arranged for funds by the Central Government to build concrete embankment in the sea facing areas, spanning 773 kms”.

“We submitted proposal to the Central Government in 2010, and they allotted around 5032 crore rupees to save these areas. Work started immediately and we were able to construct 73 kms of concrete embankment within a year”, Ganguly said.

However, he stressed that work stalled once his government went out of power. “As a result 4000 crore rupees went back to the Central coffers as the TMC couldn’t continue the work, resulting in increased sea erosion and environmental refugees”.

“The mean sea-level rise here is about 3.14 mm per year—higher than the global average of 2.6 mm,” he said”.

“As a result, islands such as Ghoramara have lost 80% of its total area in the last few decades, giving ground for the surge of environmental refugees”.

According to him, the previous Left Front government had allotted plot of lands for the emerging environmental refugees, but currently only the blame game continues.

Researchers however think all is not lost. Dr Punarbasu Chowdhury of Calcutta University and his team of researchers did extensive field work in the Gobardhanpur area. They figured out that erecting a natural mangrove barrier or creating an oyster reef in front of the concrete embankments can go a long way, preventing the complete destruction of the structures.

The findings of the study was published in a paper titled: Living shoreline, Preliminary observations on nature based solutions for toe-line protection of estuarine embankments and mangrove regeneration.

Speaking about the study, Chowdhury said, “due to extensive damming of the upstream rivers, sediment influx into the Sundarbans is decreasing day by day. As a result, the regeneration of natural mangrove forests is also taking a hit. To counter this, we placed terracotta rings infront of the embankments. Natural silt accumulated in these pitchers and mangrove regeneration started in those spots where we placed those rings”.

The study was conducted from May 2023 to April 2024. Accrding to Chowdhury, the average lifespan of a concrete embankment in the region is 10 years. However, as the flow of the sea is becoming dynamic and erratic due to the rise in global temperature, static structures can’t withstand their pressure for long. The only solution he says, is the creation of such reefs which saw success in the USA and Japan.

“Allowing people to leave behind their lands and become environmental refugees can’t be a solution. But the creation of living embankments and ensuring that the local villagers can earn a livelihood through maintaining this system can be a equitable solution”, said Chowdhury.

Chowdhury’s sentiment found echo among the farmers. For them, erosion means not just the loss of homesteads but also the steady shrinking of cultivable land. In some parts of Namkhana and Mousuni, villages have lost up to half their farmland in the last two decades.

“Earlier, we grew what we ate,” said Lakkhan Das. “Now I buy rice in the market. My sons will never be farmers.”

According to Das, his family used to own 33 bighas of cultivable land which yielded around 28 maund or around 1000 kg rice. Currently the entire farmstead is sitting under the sea, with only 2019 saw the erosion of 16 bighas.

Currently Das farms by taking other people’s land in lease. The meagre income is balanced by the ration provided by the government.

The lack of land pushes migration. A study by the Jadavpur University School of Oceanographic Studies found that nearly 25% of households in the Indian Sundarbans have at least one migrant member, often working as construction laborers in Kerala or as brick-kiln workers in Andhra Pradesh.

One evening, after a day of heavy tide, Sabitri walks again to the edge of her village. The embankment is damp, and a section has sagged dangerously. She carries a stick to steady her step. The river is swollen and brown, flecked with foam.

She squats on the edge, scoops a handful of water, and lets it fall. “It is our enemy,” she says, “and our mother. We cannot live without it, and we cannot live with it.”

When asked what she wants for her children, her voice is quiet. “A place where the ground stays still.”