Unionists in Northern Ireland gave their support to Brexit with the promise that it would bring them closer to the rest of the UK. However seven years on with an EU border placed in the Irish Sea, many feel cheated by the Brexit deal and abandoned by government. What are their hopes and fears for the future of Unionism in Northern Ireland?

In June 2016 a slightly more youthful-looking Mike Nesbitt was deep in preparation for the looming Brexit vote. As leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, the second largest pro-union party in Northern Ireland, he is adamant that remaining in the EU was the best course of action.

Mike grew up during the horror and bleakness of the Troubles. One of his earliest memories is sitting atop the Craigantlet Hills to the East of Belfast with his father as he watched the city burn beneath him.

It is because of this that Mike knows in his heart and soul that what Northern Ireland needs now more than ever is certainty and security. As a unionist, he fears that the upcoming Brexit vote will provide neither.

“I distinctly remember when I was leading the party in 2016 that it took about three milliseconds to decide that our position was to remain, it didn’t even require a thought,” said Mike. “I always thought that Brexit was a very bad idea for Northern Ireland because of our land border and the divided nature of our society.”

“I think it’s safe to say that the majority of unionists thought otherwise and favoured Brexit because it allowed for this idea of taking back control,” he explained. “What they didn’t vote for was the Irish Sea border which is seen as a subjugation of the Act of Union 1801.”

The fallout of Brexit has had far-reaching consequences for unionism within Northern Ireland. The ripple effects caused are still being made sense of.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), historically the largest in the North, campaigned in favour of the leave vote. Their expectation was that Brexit would strengthen unionism across the UK and Northern Ireland. The reality was anything but.

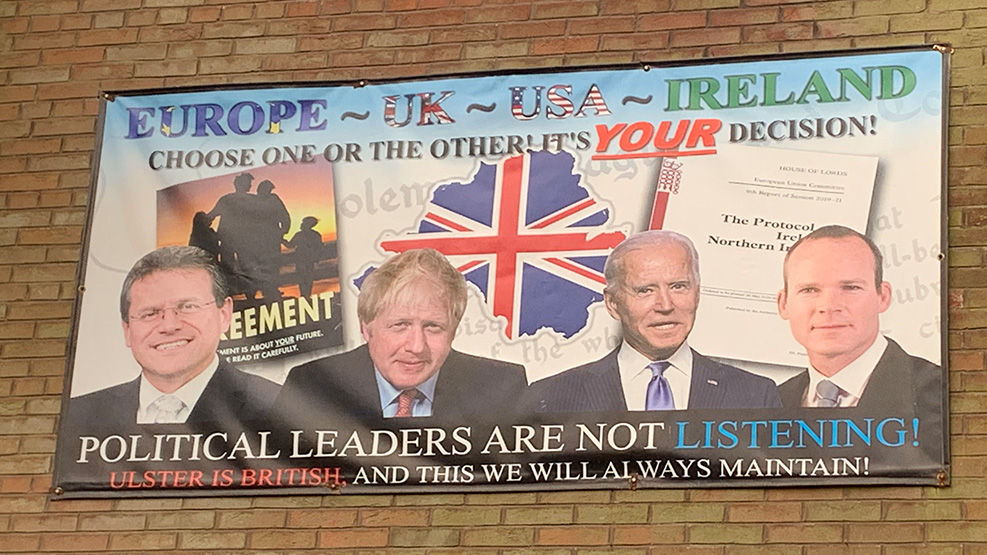

The end result is an Irish Sea trade border was established as part of the withdrawal agreement. It was called the Irish Protocol and redrafted as the Windsor Framework. This has altered Northern Ireland’s constitutional position slightly to the absolute fury of unionists.

The consequences of this contentious decision have manifested themselves as a collapsed government, a political party in perpetual turmoil, and a status quo of unionism facing an existential crisis like never before.

Mike now spends his days in his constituency office in the town of Newtownards instead of the Stormont Government buildings just a 20-minute drive away.

Much of his time is spent sitting in his office answering the phone trying to help people in any way. Something that Northern Ireland’s government has failed to do since the DUP collapsed the power-sharing government in May 2022.

“The DUP has made many strategic errors and I think that it has been damaging to unionism,” said Mike. “I think that Brexit has been disastrous for them and they are wrong to bring down the Stormont institutions because it plays into the republican narrative that Northern Ireland is a failed ungovernable statelet.”

Politically the disastrous fallout for the DUP has seen three leadership changes, a looming inner party split, and for the Irish republicans Sinn Féin to become the front-runners in the North for the first time ever.

Furthermore, the impact that Brexit has had with regard to political stability and Northern Ireland’s constitutional question has caused serious worry within the unionist community. with the trade border in the Irish Sea, there is growing uncertainty about its future within the UK.

“Above all else, the single biggest threat caused by Brexit in Northern Ireland is how it has energised Irish nationalism because it has done so in a way that I have never seen before,” said Mike. “It has been the ultimate in the reintroduction of divisive politics and I don’t think that any good has come of it”.

“Before the referendum in 2016 there was no talk about our constitutional position because it had been settled by the 1998 peace agreement, yet since the hour of the vote it has become part of the daily political discourse with neither side budging an inch on their position,” he said.

Now unionists in Northern Ireland find themselves in a position where a trade border has separated them from the rest of the UK causing a sense of abandonment and isolation. The collapsed government in protest is playing into the republican narrative and the constitutional question parked by the Good Friday Agreement has come centre stage once again.

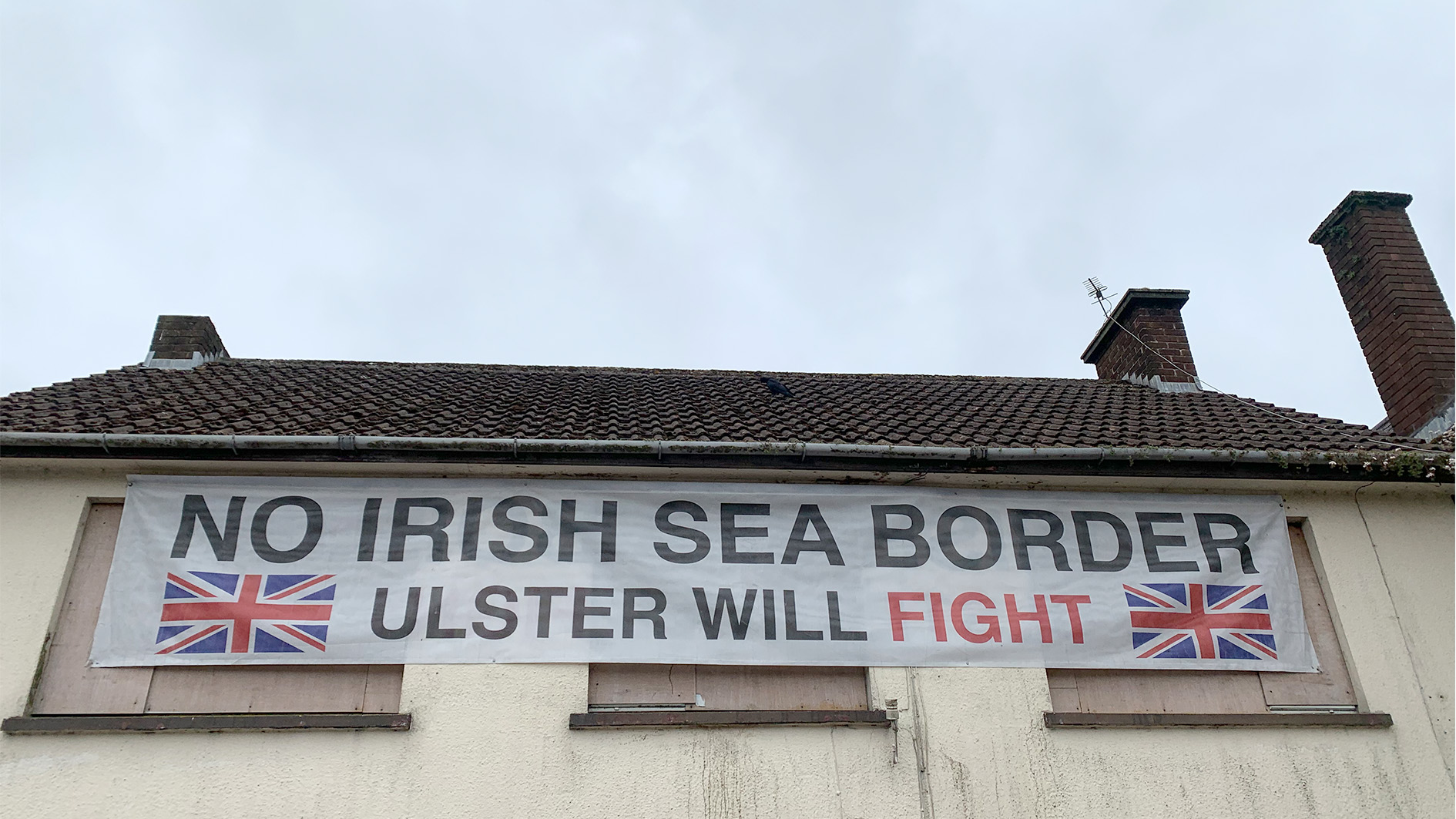

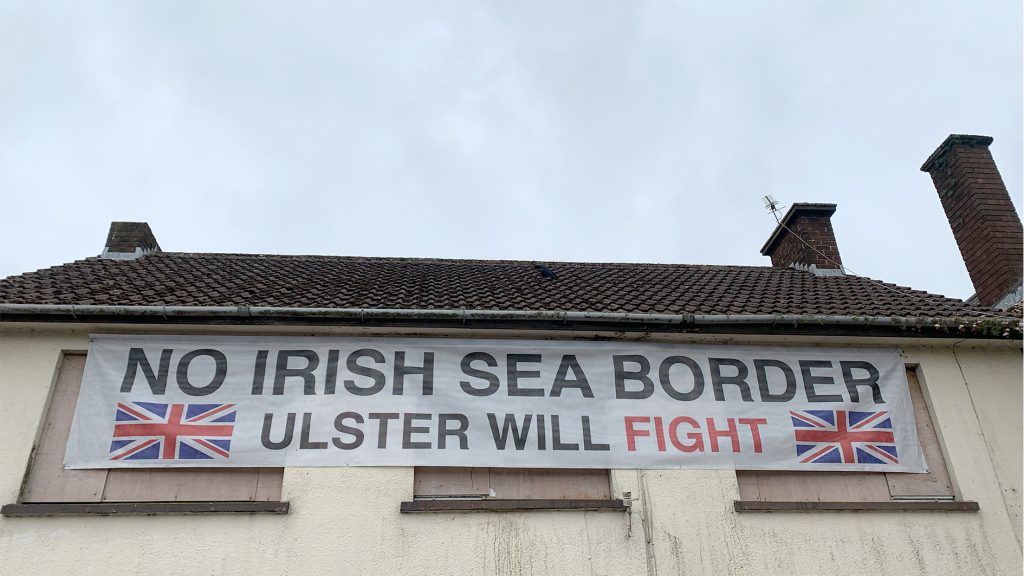

This anxiety about the future is palpable amongst the unionist community. It can be seen and felt on the street. Passing through staunchly loyalist East Belfast or in Mr. Nesbitt’s constituency of Newtownards, the colour and bunting of red, white, and blue seems far more substantial than it used to be.

There are real fears, particularly within working-class loyalist communities about the future of Northern Ireland. Martin Snodden from Belfast is an ex-loyalist paramilitary prisoner and now works in the area of conflict mediation. Martin has seen the impact that Brexit and the Protocol have had on people within his community.

“The Protocol is not simply about the border that exists at the Irish Sea ports, it’s the border that now exists in the mind and that’s the most difficult of all because a lot of people within the unionist community feel like they have been cut off and isolated,” said Martin.

The anger within unionist circles toward the protocol is understandable. Many view the border in the Irish Sea as an erosion of their place in the UK as well as the union itself.

Much of the fury directed towards the Irish and EU governments is down to how the protocol was handled, particularly by the Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar. The perceived threat of republican violence erupting in the event of a hard border played a huge part in negotiations.

“Many loyalists may have voted in favour of Brexit but they would never have voted for a border in the Irish Sea,” said Martin. “Leo Varadkar used the old tactic of it we don’t have an Irish Sea border we’re going to have a return to violence as leverage to get what he wanted which has led to huge hostility from the unionist people,” said Martin.

Worsening this hostility within loyalist circles is this feeling of abandonment and betrayal by the UK, EU, and Irish governments. Many feel a great sense of desertion by all of these guarantors of the Good Friday Agreement as a result of the protocol.

“Betrayal in capital red letters is how people feel, a great wound has reopened a trust is now a thing of the past,” Martin said. “There was no border created in Liverpool or Birmingham so why was there a need based on the leverage of Leo Varadkar to separate Northern Ireland from the rest of the United Kingdom?”

With Sinn Féin now the largest in the North and with this apparent perfect storm amplified by Brexit gathering in opposition to them, the detectable winds of change in Northern Ireland add to the worry and fear set in motion by the leave vote.

In light of these factors, there is a growing debate within unionism that it is approaching a crossroads. Demographics have levelled within Northern Ireland and it no longer is a protestant state for protestant people as It was at the time of partition in 1921.

People are splitting from the older more staunch and traditional right-wing view of protestant unionism to a more middle-ground progressive and inclusive view for the future.

“If you ask me I suggest that unionism needs to go into a room lock the doors nail the windows down and discuss what’s best for its future,” said Martin. “It needs to find a way forward in harmony and that comes from different voices coming together to create a creative and honest conversation based on trust.”

It’s a feeling that is echoed in many quarters within unionism in Northern Ireland. Jay Basra, a young activist from rural Cookstown. He is also a campaigner with the Ulster Unionist Party.

“We have to all go together or not at all because if we go too progressively unionism will split because many are still stuck in their ways,” said Jay. “I think that the best way that we can do that is by building an inclusive society with a sustainable economy because if we’re subsiding off British taxpayers were not going to be able to sell the union for much longer.”

”I think the Windsor framework gives us a chance, to do that, I know a lot of people aren’t happy about it but I’m not fussed, we can’t override an international agreement.”

Jay is of Punjabi descent and his views of unionism are in its literal sense. He believes that making life better for everyone is the best way forward. Born into the generation of peace in the new millennium his ability to see the bigger picture is something that can become clouded and obscured by those brought up during the Troubles.

“Unionism needs to do more to sell Northern Ireland and the Union to people rather than to revert to the old ideas flags and symbols,” said Jay. “We have to go above that to represent both communities because we can’t just represent our one side because that won’t progress anything.”

It’s an approach that contrasts with the abstentionist policies of the DUP. It is also the preferred way forward for Northern Ireland that Jay’s former party leader Mike Nesbitt would like to take.

Instead of focusing on the past, uniting people in a happy stable environment is viewed as the healthiest to sustain the union instead of focusing on the tactics of divisiveness employed by the DUP.

“My view is that if we all focus our energy to make Northern Ireland work then we can leave it to our children or grandchildren to answer the question on its constitutional future,” said Mike. “ We can’t rely on the traditional voting base to sustain unionism so we have to reach out and make the option of remaining within the union an attractive one.”

“If people are earning good money, having a happy family, and enjoying life, people aren’t going to vote for change, and doing so is something that I would happily devote the remainder of my political career to.”

However, standing in the way of Mike’s ambitions to work to create a better Northern Ireland for everyone is the suspended Stormont government forcing him to do what he can from his offices. Without power-sharing back then the future for this progressive approach to sell the union remains bleak.

“I think we have one more chance to make Stormont work because if we can’t we are looking at joint rule between Dublin and London and as a unionist, your fear is to what extent will the influence of the Irish government be here,” he said.

“The way to avoid that scenario is to do the job and get back to work by making Northern Ireland a better place for everyone,” said Mike. “If we can focus on that common cause together we could really fly high, if we can’t we’ll continue to get bogged down and stuck in the position we’re in now, or worse.”