London and the rest of the UK have turned to LTNs to decrease traffic and increase walking and cycling. But claims of social and racial injustice have led to an intense clash of experiences, beliefs and ideologies.

Clair Battaglino had spent nearly 40 years of her life living in a housing cooperative on Dalston Lane. She remembers the road in Hackney, London as always being dotted with the elderly walking, kids cycling and cars driving. But when she came back from a little getaway in 2020, she noticed that something had changed.

“The road was congested like I’d never seen before,” she says, assuming that maybe there was some roadwork going on nearby. “Instead, I found planters and stuff saying you can’t go through except on cycles,” she says. “In the weeks I was away, the council had implemented something called low traffic neighbourhoods.”

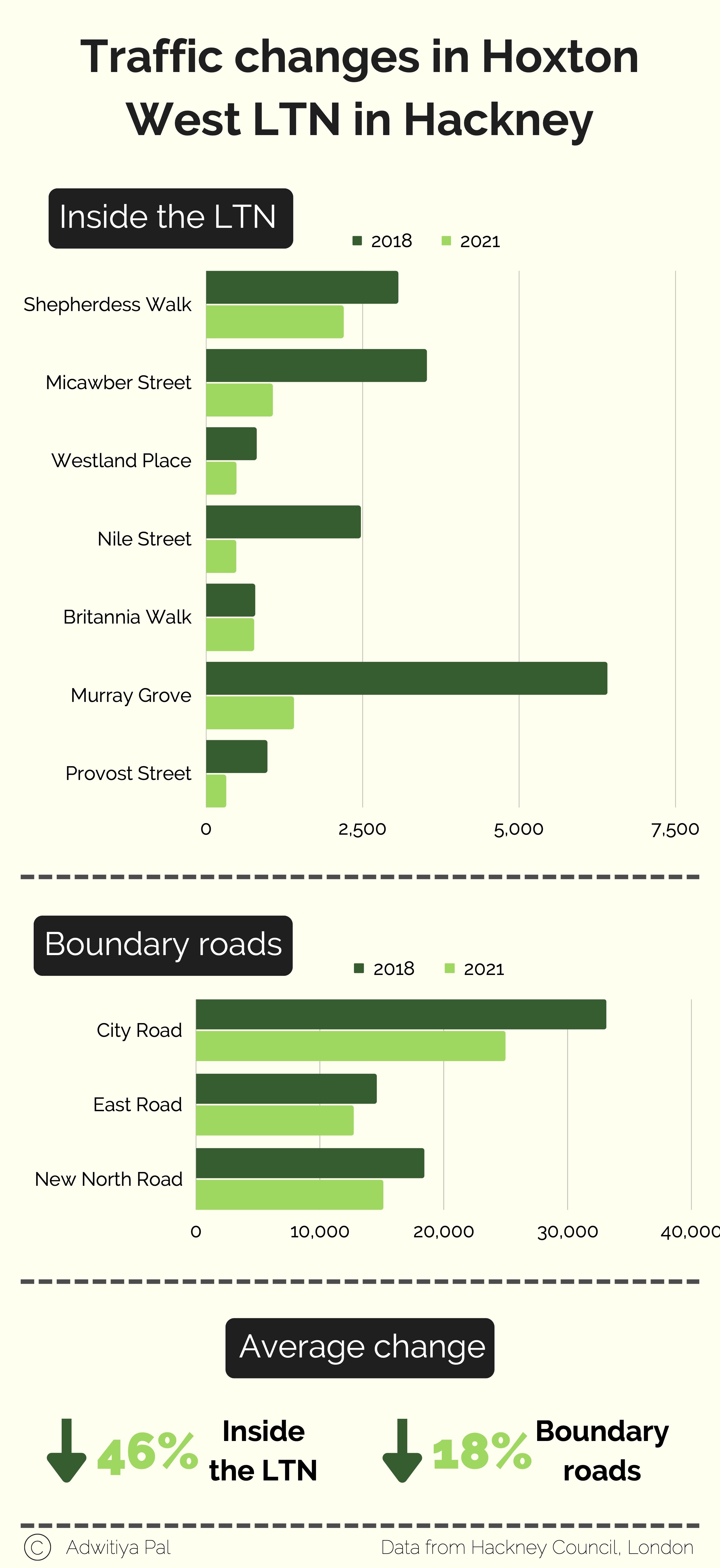

According to Transport for London (TfL), over 100 low-traffic neighbourhoods, or LTNs were introduced in London between 2020 and 2021, the streets next to Clair’s house being a couple of them. With a combination of traffic filters like planters, bollards and bus gates, LTNs restrict the movement of private vehicles. However, critics like Clair argue that they unfairly displace traffic onto the streets that do not have the privilege of being in an LTN.

“For me, it’s been terrible to go from loving where you live, a purely residential area with social housing, to seeing that become a complete mess,” says Clair over the honking of cars passing by her living room.

LTNs are based on the concept of behaviour shift and traffic evaporation — a theory that if you make it difficult enough to drive, people will ditch cars for other modes of transport. They are recognised by TfL and a majority of transport experts as being crucial for improving walking and cycling, or active travel rates.

While these outcomes have benefits like less traffic, better air quality and quieter and safer roads, climate activist David Smith says that these measures have failed in their execution. “On the face of it, it’s a great idea,” he says. “But the problem is that people like their cars. Their tolerance of sitting in heavy and slow traffic is very high.”

According to David, since drivers cannot use the residential roads in an LTN to shorten their journeys, they are forced to take longer routes, resulting in more vehicle miles driven, and consequently more toxic fumes and pollution. Most of these displaced cars end up on the main roads that are inhabited predominantly by the working class and those from the black, Asian and other ethnic minority communities, he says, thus only disproportionately benefitting the wealthy and the upper class.

“It’s a social injustice. It’s racial injustice. It’s just a PR marketing exercise of finding a way to close the roads for the most affluent,” he says. “They’ve managed to very carefully create this illusion, this story that by making life better for themselves on side roads, it’s benefitting everybody. But actually, it’s harming those on the main roads who are already most at risk.”

Even with all the consultation, you can’t overcome the deep divisiveness of LTNs.

John Stewart, transport campaigner

Clair lives on Dalston Lane which is one such designated main road, or ‘sacrificial road’ as she calls it. She says that there’s been an overflow of traffic on this road in the last two years. But this also comes at health costs. She was recently issued a peak flow test and an inhaler by her GP. “It’s a direct result of the rising air pollution levels due to congestion,” she says.

Clair’s not the only one being monitored for asthma. “There are many people on this road. There’s a woman a few houses down, who has been put on a second inhaler, and I hear this story again and again,” she says. “It gets very depressing and upsetting to have our experiences denied. It’s just been absolutely horrible.”

It’s not just the elderly who are suffering. Dalston has a number of nurseries, primaries and middle schools — all with a large intake of children from minority communities like South American, Asian, Middle Eastern and African. Clair, who used to be a teacher herself, says that she went to The City Academy in Hackney to measure the air quality index there. She found that the particulate matter (PM10) readings were over 100, on par with what’s considered ‘very high’ pollution levels by the UK government.

While these children are threatened with stunted lung growth due to pollution, they are also faced with the risk of traffic accidents. In 2020, over 1600 children under 15 were injured in the country while cycling, with nine of those injuries being fatal.

On the other side of Hackney is the Gayhurst Community School, located in a posh, mostly-white neighbourhood benefitting from road closures, where children can be seen casually strolling, or riding their cycles with their parents without any traffic on the roads. “The children near my house are in direct danger from cars. Are the lives of some children not as important as the others?” asks Clair.

But beyond all the heated arguments and polemics, numerous studies have refuted the claims made by LTN critics. A report by the climate charity Possible, authored by active travel expert Dr Rachel Aldred from the University of Westminster, found that there was barely any difference in demographics between the percentages of the white population and other ethnicities living on main roads and residential roads in London.

Another report by the think tank Centre for London showed that there was no evidence to claim that LTNs displace traffic from residential roads to main roads. In fact, recent findings from the Healthy Streets Scorecard programme show that car ownership has gone down the most in councils which have the most LTNs.

Despite all the studies and findings, why is there such a strong opposition toward LTNs? Cyclist and campaigner from Hackney, Rob Richter* believes that people are being close-minded and hopping on this bandwagon of distrust towards LTNs.

“People seem to have lost the ability to tell fact from fiction and jumped to conspiracy theories,” he says. “You can have a scientific paper published in a respected journal and they will not accept it. There’s this sort of fake news aspect, where everyone is so suspicious of anything coming from a public source that it is difficult to convince people, despite all surveys showing that over time people love LTNs.”

One instance of people falling in love with LTNs can be traced to De Beauvoir in Hackney, an estate that has had traffic filters since the 1970s. It’s a quiet, green area with minimum car traffic and an abundance of people walking and cycling. “If you went there and said to people ‘we would like to pull out your LTNs’, there would be an absolute uproar,” says Rob. “It’s just a case of implementing them and dealing with that initial reaction.”

Similar success stories can be found in other boroughs of London like Waltham Forest, where LTNs were introduced in 2014 as part of the Mini-Holland trials. Car ownership since then has fallen by 20% and people are spending 45 minutes more walking or cycling in a week, according to research conducted by Dr Aldred.

Sarah Berry, an active travel campaigner, had the opportunity to experience the LTNs in south London two years ago. When they were put in place in Lambeth during the lockdown, she felt that it was the perfect time for her to get a bike and start using it, after years of avoiding one.

“I just started to see so many different types of people riding their bikes, mums with their kids, dads with their dogs, young kids cycling on their own and people who were shopping,” says Sarah. “It wasn’t just people doing it for sport. It was people doing it as a means of getting around and also having a really fun time doing it. It changed my perspective.”

However, the timing of the LTNs and the speed with which they were implemented are probably reasons why people have such visceral reactions toward them, says Sarah. “They were introduced during Covid, a time when people were feeling like things were really out of their control. So having something else like that taken out of their control was like the straw that broke the camel’s back,” she says.

To resolve this discontent, LTN advocates are calling for better messaging to make the schemes more appealing to people. Jeeshan Choudhary, communications officer at Centre for London calls for a detoxifying campaign in an effort to rebrand the LTNs and deliver the research in a way that’s accessible to the public.

“It’s very easy to spread myths about LTNs because theoretically, the idea of shutting traffic in one area makes you think that it will increase traffic somewhere else. But it needs to check out with the data,” he says. “We studied a set amount of LTNs within London and from all the data we compiled, there was no evidence that boundary traffic increases substantially, but instead walking and cycling did.”

The solution to repairing the bridge between LTNs and residents, according to Jeeshan, is consultation. “This isn’t about helping the privileged few or helping specific neighbourhoods,” he says. “This is about reducing private car usage and encouraging the shift to greener modes of travel. And there needs to be a concerted effort to make sure that all residents are aware of that.”

However, John Stewart, a transport campaigner for the last 40 years, disagrees with this solution. He says, “Even with all the consultation in the world, they can’t overcome the deep divisiveness of LTNs.”

John, a resident of Dulwich in London has seen people from all parts of the borough stick together over the years. But that’s no longer been the case since the arrival of LTNs. “They have set one person against another, people who’d have gone to the same restaurants, been friends and all,” he says, as people have started questioning the privilege of those living within LTNs. “There’s no doubt about a division.”

Another problem with LTNs, according to John, is that they are getting in the way of developing more radical transport policies to reduce congestion and curtail air and noise pollution. “The big challenge for authorities is how do you bring about less traffic in a fair and equitable way,” he says. “We have to try and build up a coalition of support amongst the general public, which is becoming really hard with LTNs being so divisive.”

Jeeshan disapproves of this approach of criticising LTNs without proposing a solution. “What’s the alternative? Often this question leaves a lot of critics stuck,” he says. “Anti-LTN advocates need to be able to answer this question in order to be part of this debate. Because if the answer is just to scrap LTNs and continue with the way things are now, we know that’s not good enough in terms of decarbonisation, climate change and our air quality.”

But David, who has worked with Extinction Rebellion over climate issues, is quick to call out these schemes for greenwashing. “We’re all part of the same ecosystem. You go and protect yourself and your own streets from air pollution, but that doesn’t protect you from climate change,” he says. “This is what is happening around the world. People are looking at ways to take climate action that benefits themselves rather than take climate action that benefits everyone.”

While a number of councils in London have made it clear that low-traffic neighbourhoods are here to stay, local bodies throughout the country are following suit. Councils in cities like Birmingham, Manchester, Oxford and Edinburgh, have committed to the idea of LTNs as one of the most important tools to tackle congestion and pollution and increase walking and cycling.

Actions like these are alienating anti-LTN campaigners such as David. “My faith in these institutions just isn’t there because they’ve already made up their minds that LTNs are successful, when our experiences say that they’re not,” he says. “We should be finding a better solution, but we’re not because this solution benefits those who put it forward, because they’re the only people around the table.”

John Stewart says that there’s a lot more to come in this battle before either side wins. “It may take years, even decades,” he says. “If people feel like they’re being wronged, or there’s an injustice, there’s at least some people who won’t give up. And usually, it’s the beginning of some sort of campaign or movement. If I were to make a prediction, I think that these people will continue campaigning, probably even more coherently and strongly.”

*Name changed on behalf of interviewee’s request to stay anonymous