Tougher visa rules, increased anti-immigrant sentiments, and a dwindling job market. Why are Indians dropping their plans to study at British universities?

When Mahalakshmi Gururaj secured admission to the London School of Economics, she was ecstatic. Months of research, draining application processes and the nervous wait were finally over.

Then a notification popped up on her phone. ‘UK reduces post-study work visa to 18 months,” an Indian news platform announced.

“Getting a degree and working in the UK was a dream,” Mahalakshmi says. “But I wondered if it was worth it,”

The admission advisers tried to reassure her that the changes would not affect the batch of students immigrating in 2025, but the uncertainty and financial investment were too significant to risk.

“A lot of people told me that the new student visa rules would not apply to me,” the 21-year-old media student says. “But a one-year degree in the UK would cost me around £50,000. I had been applying for scholarships but could not get any. In the end, I wondered if I would ever be able to justify the investment I am making?”

Sourav Goswami wanted to pursue a PhD degree from a UK university, but seeing the rise of the right-wing parties and the changes proposed in student visa rules, he decided to seek admission into the University of Oslo.

“It’s not only about doing a PhD. It’s also about how you are treated and if people are welcoming. The populist rhetoric is all over in Europe, but it seems to be worsening in the UK,” 35-year-old Sourav says.

He believes the UK is losing on talent from across the world because of its internal politics.

“I personally know a few students, friends of mine with an economics background. They studied at the Delhi School of Economics and later secured admission to UK universities. But one chose Sorbonne University in Paris, another went to the University of Barcelona, and a third is at the University of Pisa in Italy,” he says.

Like Mahalakshmi, Sourav and his friends, the UK government’s proposed changes to the student visa rules, the anti-immigration rhetoric, and the dwindling job market are deterring thousands of Indian students from choosing British universities for higher education.

Government white paper and changes to student visa rules

In May 2025, the UK government published its immigration white paper titled ‘Restoring Control over the Immigration System’, laying out plans aimed at reducing net migration.

One of the most significant proposals involves reducing the post-study work period for the graduate or post-study work (PSW) visa, which permits international graduates to work or seek employment after completing their degrees. Under the suggested plan, non-PhD graduates would see their stay shortened from two years to 18 months, while doctoral graduates might keep a three-year allowance.

The paper also raises compliance standards for higher education institutions sponsoring international students. To retain their licence, they must ensure a 95 per cent enrolment rate, 90 per cent course completion, and visa refusal rates below 5 per cent.” A new red-amber-green rating system will publicly rank institutions on compliance.

Further measures include a 6 per cent levy on international tuition fee income, earmarked for reinvestment in the UK’s skills and education sector, and tougher English language requirements for adult dependents of students.

Instead of filling universities with the cream of our own youth… we import dumbed-down foreign cash cows from competitor nations, The Telegraph columnist Allison Pearson.

Changes deterring Indian students

An education consultant associated with the British Council in India said that since the British government unveiled its plan to reduce migration numbers, queries from students interested in UK universities have plummeted.

“I can tell you that compared to 2024, the number of students interested in going to the UK has dropped by almost 40-45%,” he says.

Sakshi Mittal, founder of New Delhi-based education consultancy University Leap, says the graduate visa scheme has been a major attraction for Indian students, and even the talk of truncating it is causing panic.

She says when the two-year post-study work visa was reintroduced in 2021, it spurred a surge in Indian students choosing British Universities for studies

“The UK became one of the top preferences for Indian students after 2021,” Mittal says. “We suddenly saw students who were earlier interested in going to the US, Ireland or Australia switch to the UK. Everyone wanted to go there. But now, there is a general sense of panic, and we are not sure what the government is going to achieve by reducing the PSW visa by six months.”

Mittal says the lack of jobs is also discouraging Indians from travelling to the UK.

“In the past one or two years, the feedback we get from students in the UK is that it is extremely difficult to find a job. It has become common knowledge that there is absolutely, for the lack of a better word, no jobs at all for international students over there,” she says.

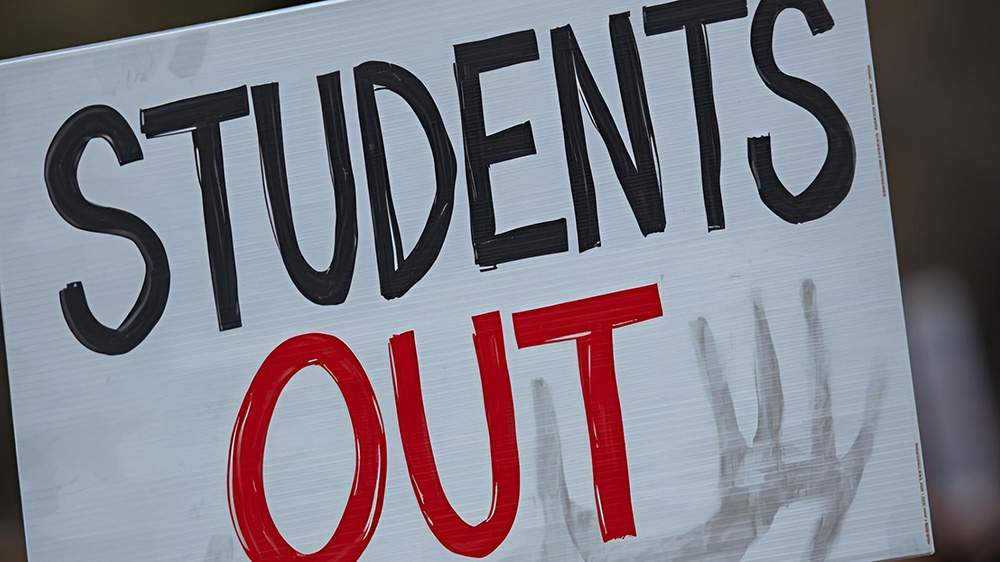

Then there is the rise of populism in Britain and the right-wing parties and commentators’ criticism of universities’ preference for foreign students.

According to the Home Office, 403,000 sponsored study visas were granted to international students in the year ending March 2025. This accounts for nearly half (46%) of all non-visit visas, excluding tourists and short-term visitors. It was 10% fewer than in the year ending March 2024, but 50% higher than in 2019.

This surge in student numbers has garnered severe criticism from right-wing commentators and the media.

Only international students with essential skills can remain in the UK, Reform UK’s 2024 manifesto.

In January 2024, The Daily Telegraph columnist Allison Pearson said that the Universities’ preference for foreign students “practically amounts to apartheid”.

“So, instead of filling universities with the cream of our own youth, crucial for future economic growth and prosperity, we import dumbed-down foreign cash cows from competitor nations. Anyone else spot the potential drawback here or is it just me?” she wrote.

In its 2024 manifesto for the general election, Reform UK promised new visa rules for international students and said it would ban students from bringing in family members as dependents.

“Only international students with essential skills can remain in the UK. Close down fake courses and immigration schemes that abuse the rules,” the party promised.

The populist party led by Nigel Farage won only five seats in the last general elections, but its popularity has since skyrocketed. A YouGov poll released in June 2025 projected it to win 271 out of the 650 seats in British Parliament, more than any other party, if an election took place this year.

Many see a connection between Reform’s rising appeal and the Labour government’s plans to change immigration laws.

Chris Millward, Professor of Practice in Education Policy at the University of Birmingham, noted that just two weeks before the release of the immigration white paper by the government, the Reform secured control of ten local authorities across England, winning 677 seats.

“The party’s rising popularity will be of increasing concern to the Labour government,” he wrote on the online news platform The Conversation.

Millward argued that Reform is concerned about the effects of immigration on communities and wages, and this affects international students because they figure in immigration statistics and increasingly stay for work.

“Like nationalist and anti-immigration parties in other countries, Reform also gains more support from voters without a university degree. In the US and the Netherlands, similar movements have taken steps to reduce university funding and international students once in power,” he says.

But these policies are not confined to nationalist parties, Millward adds.

“Canada and Australia’s Liberal and Labour governments also signalled caps on international student recruitment before their re-election earlier this year. This appears to be the strategy adopted by the UK’s Labour party – that it wants to assure voters who are more concerned about immigration than university finances,” he says.

International students easy target to control immigration

The UK government’s policies on international students have historically been inconsistent, and it is most visible in the trajectory of the PSW visa.

The full-recognised two-year PSW visa came in 2008. It caused a surge in the number of international students. Four years later, the Conservative government, with Theresa May as Home Secretary, scrapped the policy to bring the net migration down.

Student enrolments from India, one of the UK’s largest markets, fell by more than half. Universities, heavily reliant on overseas tuition fees, saw financial pressure mount, while competitors such as Canada and Australia attracted students who might once have chosen Britain.

UK is losing on talent from across the world because of its internal politics, Indian student.

By 2019, with universities lobbying hard and international education recognised as a strategic asset, the government announced the reintroduction of a two-year Graduate Route. The policy was implemented in 2021, again causing a surge in the number of international students.

Dr Andy Williams, Senior Lecturer in media and culture at Cardiff University, says that the targeting of international students is one of the most concerning phenomena of British politics over the last 15 years.

“International students have been swept along with the broad anti-immigrant sentiment that has become normal,” says Williams. “It’s getting worse. It’s an awful problem because it’s making Britain a more insular, more narrow-minded, more intolerant, and a more racist place as well.”

Williams says his students have been attacked, intimidated and shouted at in the streets.

“It’s because of the political climate that our governments have fomented by not standing up to those far-right actors within society, by not pushing back against the worst of the kind of hate that gets spread around by our media system,” he says.

Universities’ reaction

Universities have pushed back against the changes proposed. Universities UK, an advocacy organisation representing over 140 British Universities, acknowledged that international students bring huge benefits to high streets, workplaces and campuses across the country.

“They contribute billions to the UK economy each year, while the fees they pay help ensure there are more places for British students – especially in subjects like engineering, which cost universities far more to teach than they receive from the UK government, but are vital to the UK’s long-term growth and prosperity,” the group’s Chief Executive, Vivienne Stern said in a 3 June, 2025 statement.

Stern said that the government needs to work with the Universities to address the financial sustainability of higher-education institutions.

Students abandoning the UK for other countries

Indian education consultancy firm University Leap’s Mittal says the UK was poised to gain more Indian students due to the political climate in the US and India’s diplomatic row with Canada over the alleged killing by Indian agents of a Canadian citizen.

However, the country’s proposed revision to visa rules has made it an unfavourable option for many Indians, who are now opting for universities in Europe.

“These students are going to places like Ireland, France, Germany and Australia,” she says.

Dubai has emerged as a surprisingly attractive destination for students in the last two years, Mittal argues.

“A student thinks it is difficult for them to get into an Indian university, and they don’t want to get into debt by investing much in the UK, especially given the current job market and political climate. So, they choose Dubai as the alternative. And there are plenty of good jobs there as well,” she says.

Universities in Dubai, Mittal adds, are economical, and the visa process is also hassle-free.

“If a student were to migrate from Delhi to let’s say Mumbai or Bengaluru to study at a private university, the fee and the living expenses are almost huge and almost like moving to another country. So, the student says I would rather pay a little more and travel to Dubai,” she says.

Dubai has emerged as a surprisingly attractive destination for students in the last two years, Sakshi Mittal, education consultant.

Some Indian students have given up on the UK dream and decided to stay in India and study at Indian universities.

After Mahalakshmi dropped her plans to study at LSE, she relocated to the nearby state of Karnataka and is pursuing a master’s degree there.

The curriculum and the teaching may not be as good as the LSE, but the two-year degree would cost her around £10,000, a fraction of the tuition fee and living costs in the UK.

“I was more inclined to go into research. Most media degrees here in India are not focused on that. But right now, this is the best option,” she says.