As UK higher education institutions face financial deficits, many are turning to international students to fill the gap, but at what cost?

In her first week at a top British university, Roshni Kukreja was asked to interview a classmate. It was a bonding exercise and an introduction to the fundamentals of journalism. But she was shocked to find that the person she was interviewing spoke barely any English.

The two communicated through Google Translate.

“I didn’t know what to do. We were asked to interview each other, find something interesting and common. But here we were, relying on an app to understand what the other is trying to say,” says Roshni, who asked for her name to be changed for the story.

Roshni chose the university for its top ranking and its membership of the Russell Group, an association of 24 public research universities in the United Kingdom, known for their strong focus on research and academic excellence.

Over the next few months, she witnessed her classmates recording lectures on phones, using live-translation software and relying on artificial intelligence (AI) to complete assignments.

“Many students just hung out with those who spoke the same language. The group projects were nightmares,” she says. “Some students just did not want to participate. Texts and emails remained unanswered and many rarely showed up on classes.”

There’s constant pressure from the managers in the university to get more students through the door by lowering standards in terms of their English language and their general qualifications, faculty at Russell Group University.

Roshni’s experience is not unique. As British Universities struggle to stave off financial crises, there is a widespread concern that many of them are lowering their educational and language requirements to rope in more foreign students, creating challenges for the faculty and students spending fortunes to get degrees from reputed universities.

Lowering entry standards and deceptive tactics by agents

A faculty tasked with recruiting students at the undergraduate level in one of the top journalism schools in the UK says there is increased pressure from the University management to enrol foreign students, even if they do not have the required language and academic skills.

“There’s constant pressure from the managers in the university to get more students through the door by lowering standards in terms of their English language and their general qualifications. That has had a marked effect on our ability to adequately teach the whole cohort of students that we get at the required standard,” he says, requesting anonymity because the information is confidential.

The pressure has resulted in the school lowering its admission standards for international students.

“On the undergraduate programmes that we run at the moment, the standard offer for A-level home students is ABB. But if you’re an international student, the standard offer is three B’s, that’s BBB,” the faculty says.

He says the university also made the school bring down the IELTS score requirement.

These changes have created conditions where an increasing number of students do not have the required academic or language skills to participate in lectures and projects.

“Sometimes it is even as bad as the students just don’t understand anything that you’re saying in the seminar. If you’re supervising them for a dissertation, very often those with the worst English language won’t engage with the dissertation at all. They won’t come, which means that they’re missing out on a big part of the value and education that they paid for,” the faculty says.

In some supervision meetings, a few students were accompanied by friends or proxies who helped them translate the teacher’s instructions.

“Very often they are recording, not in a way that they can go and listen to it again for some extra value but recording for basic comprehension. It doesn’t happen hugely often, but it happens more often as time goes by and that’s a problem,” the faculty quoted above says.

He adds most international students are hardworking and talented in their fields, but the odd instances are becoming frequent.

An English language tutor at a Russell Group University revealed there are increased concerns about the students being admitted into the university through agents, with no knowledge about courses or the modules they will study.

“Last summer, I had a class of online students, and they were all hoping to go do one-year master’s courses. I think probably about 80% of them were going to the business school. I asked them what they knew about their courses, what they’d found out. I think all of them knew the name of their course, and that’s it. That’s where it stopped. Nobody knew the structure of the course. Nobody knew the names of the modules or anything like that. Everybody had got 100% of their information about the university from an agent,” he says.

Every year, he sends his feedback about the students’ struggles and their being overwhelmed, but rarely does the University act on it.

“I think the incentive is probably economic and not necessarily ethical or practical,” the tutor says.

Dyfrig Jones, a professor at Bangor University in Wales and Vice President of the University and College Union (UCU), a body representing over 120,000 members of staff at higher education institutions in the UK, said he is increasingly hearing his colleagues complain about the issue.

“It’s become a problem where I’ve increasingly heard people say that it’s an issue more and more as the years have gone by. Certainly, if you go back 17-18 years when I was starting to teach in higher education, it’s not something that you would have heard that much. I had no experience in the early years of coming across anything but perfectly fluent English speakers,” he said.

Amoral agents luring foreign students

Many universities have been paying agents in countries like India, China and others to fill seats with foreign students. Often, these agents are pushing students with little to no knowledge of the English language or poor grades.

To students, they offer colleges paying them the highest commission, which can go up to 20% of the first year tuition fee or around £4,000 for a course that costs an international student around £20,000.

I directly speak to the universities. So, I can explain your case to them and then get your thing solved, said an agent.

This reporter contacted an agency called Infinite Solution, posing as a prospective student seeking admission to a journalism course in the UK. The agency initially provided a list of top British universities. Later, they shared the contact of a man named Girish, who claimed to be based in London and working as an international student recruiter. He said his role was to facilitate admissions, internships, and placements for Indian students aspiring to study in the UK.

In a conversation in July 2025, Girish said that he could offer a place at an obscure university in London. When asked about Leeds or Cardiff Universities, both part of the Russell Group and known for their journalism courses, Girish said admissions to them have closed.

“Cardiff is closed, Leeds also,” he said. “If you could have contacted me, let’s say fifteen days or two weeks or one week before, I would have pushed you. I was in Cardiff last week. But maybe we can squeeze you into this, and we can arrange some scholarship as well.”

Notably, these universities were part of the list Infinite Solution had provided a few weeks before the conversation with Girish. The websites of both Cardiff University and Leeds University revealed that admissions to their journalism courses were still open.

Girish then offered a place at another London University, ranked below 400 in the QS World University ranking. He claimed to in direct touch with these universities and promised to arrange the Confirmation of Acceptance for Studies (CAS) letter, a document issued by UK universities essential for visa application, within a week.

“I would say do not waste time because you can come here in the next month itself. I can finish the process quickly because, you know, I directly speak to the universities. So, I can explain your case to them and then get your thing solved,” he said.

Monika Saini (name changed) has worked with an educational agency in India for 17 years. She says for agents, admissions is a business, and they sell products to students, which can get them the highest commission.

“It’s pure business. Many universities say that the more students we give them, the higher our commission will be,” says Saini, while asking her name to be kept anonymous.

Saini says there are agents who are even forging education documents to send students to foreign universities, but those “packages” come at a higher price.

“I know people who charge around 15,000 pounds to sort everything for you. If you have low marks, they will give you a new marksheet, they will write your essays and your assignments too. It’s an open secret. Once you go in the market you will find all this happening. Nothing is shocking about it,” she says.

Girish and Saini corroborate an undercover investigation by The Times newspaper last year, revealing Britain’s top universities are paying middlemen (agents) millions of pounds to recruit lucrative overseas students on far lower grades than those required of UK applicants.

Cash-strapped universities over-reliant on international students

Office for Students (OFS), the independent regulator for higher education in England, said in a May 2025 report that four in 10 Universities are running a deficit, and the primary reason for the deterioration is lower than anticipated levels of recruitment of international students.

20 per cent of UK universities’ total income came from the tuition fees of international students, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

It said that the medium-term pressures on universities are “significant, complex and ongoing” and if the number of student entrants is lower than forecast in the coming years, the sector’s financial performance could continue to deteriorate, leaving more institutions facing significant financial challenges.

“Our independent analysis, drawn from data institutions have submitted, once again starkly sets out the challenges facing the sector. The sector is forecasting a third consecutive year of decline in financial performance,” Philippa Pickford, Director of Regulation at the OFS, said in a statement.

A survey conducted in March 2025 by Universities UK, an advocacy group representing over 140 British Universities, revealed that nearly half of the total universities in the country closed courses or cut optional modules to reduce costs.

It found that a quarter of universities have had to make compulsory redundancies, and as many as 88 per cent said they may need to consider further course closures or course consolidations over the next three years.

“Falling per-student funding, visa changes which have decreased international enrolments, and a longstanding failure of research grants to cover costs are creating huge pressures in all four nations of the UK,” said Vivienne Stern, the organisation’s Chief Executive.

A research published by the London School of Economics in July 2025 found that the real value of domestic tuition fees has fallen by around 20 per cent over the past decade, as fees have remained largely frozen while inflation has surged.

This shortfall has pushed universities to depend increasingly on higher international fees to subsidise teaching and research.

While the fee for home undergraduates is capped at £9,535, international students are often charged more than three times as much. For instance, the four-year BSc Data Science course at the University of Bristol costs £30,400 per year for an international student. At the University of Warwick, a degree in Accounting and Finance is priced at £33,520, while a Chemical Engineering course at University College London (UCL) approaches £40,000 annually.

The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change argued, in an article published in June, that in the 2022/23 academic year, nearly 20 per cent of UK universities’ total income came from the tuition fees of international students.

The average cross-subsidy from international students towards the cost of education for domestic students was estimated to be around £2,588 per year.

Falling foreign student numbers raises alarm

In June 2024, the House of Lords found that while nearly a quarter of total students at British Universities in 2023-24 were from overseas, it was down 4 per cent than the record highs the previous year, the first fall in over a decade.

“The number of student visas granted increased to a new record of around 484,000 in 2022 before falling by 5% in 2023 and 14% in 2024. Applications for study visas in August (traditionally the peak month) were 17% lower in 2024 than in 2023,” the House of Lords report said.

Many say the government messaging has fuelled the uncertainty more.

In July 2024, Education Secretary Bridget Philipson said the Labour government welcomes foreign students and acknowledges their contribution to the UK economy.

At the same time, the government also pledged to bring down the immigration numbers, a move expected to have a major impact on foreign students as they make up the highest proportion of immigrants to Britain.

“Recent visa restrictions — such as the removal of dependents’ rights for international postgraduates — have already deterred applicants. The latest Immigration White Paper proposes even stricter rules: raising the minimum pass threshold in the Basic Compliance Assessment, shortening post-study work rights, and potentially introducing a new 6 per cent levy on international student income,” the July 2025 LSE research argued.

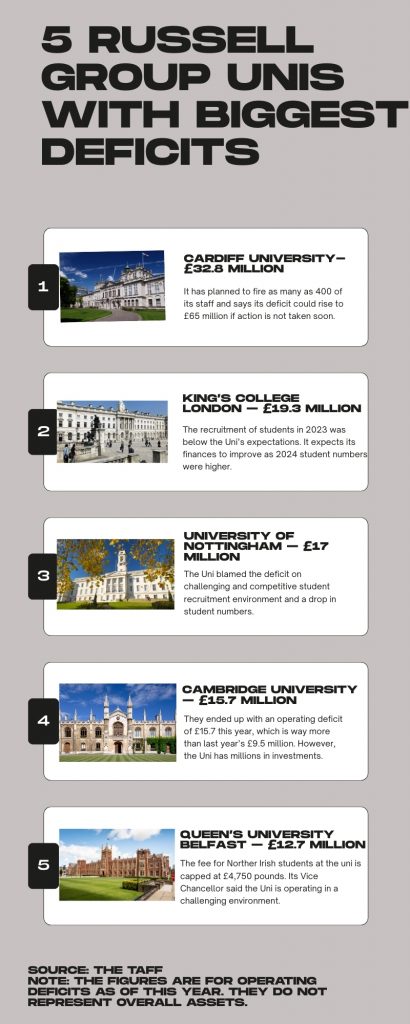

To stave off the crisis, some universities have decided to cut staff and cancel courses to manage their balance sheets. Durham and Newcastle have laid off nearly 200 people each. Lancaster may fire 20 per cent of its staff, while Cardiff has proposed to cut 400 staff and drop subjects like music.

They are calling on the government for support and warning that they are under huge pressure with more job cuts on the horizon.

“We need governments in all four nations of the UK to do their bit. That means increasing per student funding; stabilising international student visa policy; and working with us to sort out the research funding system,” Universities UK’s Stern has said.