Popular for 45 years, microfinance has helped millions of people to start businesses in the developing world. Yet with stories of debt and corruption is it time for all charities to put more focus on financial training for the people they are trying to help?

It’s tobacco season in Malawi, and looking across the now empty field, Katherine* know her work is done. However, when she got home she learned that her husband has blown all the money on a new roof for their house.

She was now stuck. When they harvest the money tends to all come at once. How would she make the little money she has left last all year? How would she pay for food? Or for next years crop season?

Farmers like these often turn to organisations such as Opportunity to get small loans to invest in their livelihoods. However, this is not before organisations can make sure they are equipped with the skills to use these loans effectively.

“If you just give people access to financial products without the training, they may not be making the right choices,” said Sally Vicaria, Opportunity’s Director of International Programmes. “They may not know how to budget their money, they may not know how to save.”

Many microfinance organisations have evolved so that they no longer give people access to loans or savings without making sure they actually understand how to use them. It’s important, Sally explained, that if you are giving loans to the most marginalised that you give at least an essence of training for them to know how to manage their money.

Microfinance is the provision of small loans, insurance, savings and other financial services for often poor communities who wish to become more economically active. Much microfinance also now includes training for its customers.

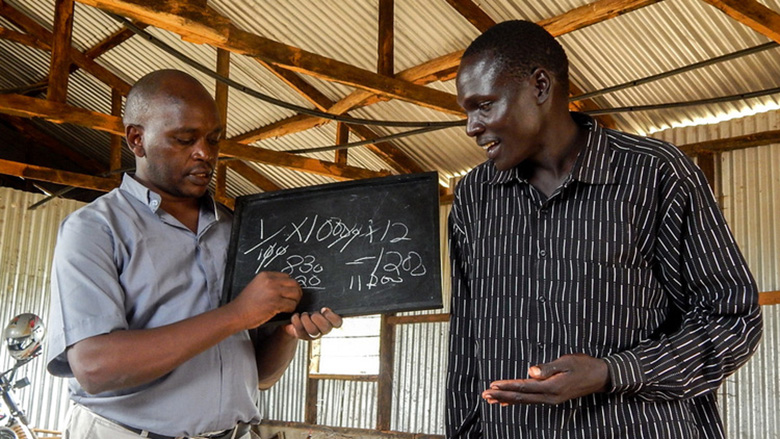

For Opportunity, its training is done by loan officers who train all clients on basic financial skills related to earning, spending, budgeting, and borrowing money.

“When we ask those [who have got a loan] one of the things that came out so clearly was that, yes, they love to have access to financial services, but it is the training that they receive, … for example, we will teach them how to really price up their goods, or how to negotiate for a better price and how to manage their business,” said Lydia Baffour Awuah, Senior Programme Manager at Opportunity. “Those things they find very, very important.”

Academic Todd Watkins, believes microfinance got a few ‘black eyes’ in the early 2000s. A scourage of suicides from over in-debted borrowers in Andhra Pradesh in 2010 and lacking regulations magnified this. He explains that in this period microfinance lost its belief that it could solve every problem in poverty and got jaded in the process.

“People were seeing it do things, as it tried to expand that probably weren’t in the best interest of the clients,” said Todd. “It got a reputation, … I think unfairly in some ways got a reputation for kind of taking advantage of clients in terms of charging high prices.”

Hannah Wichmann, Programme Manager at Five Talents, explains when you are working with those with a lower education rate, it must be training first loan second.

“Loans obviously come with a level of risk but we want to make sure we can mitigate that as much as possible,” said Hannah. “We found that the best way to do that is kind of pre-emptive before the loan is given in the 1st place rather than trying to follow up once it’s not been repaid because at that point it was probably a loan taken not at a wise time.”

To many organisations, financial training is that pre-emptive measure.

There is very little to no quantitive research on the success of microfinance before and after financial literacy training. However, research from Academics such as Vivek Gupta highlights that in some countries such as India it is loan first, loan second, and loan third and training is never even considered.

“I think even loan officials are not properly trained on how they must impart [training] onto the loan borrowers …,” he said. “When the loan provider and the loan agent is not sensitive on such issues then how can a borrower be sensitive about it.”

Vivek strongly ties suicides from microfinance to a lack of training or knowledge given to the borrowers of how to use that loan. He believes it is no surprise that India has one of the highest rates of suicide but also one of the lowest rates of training.

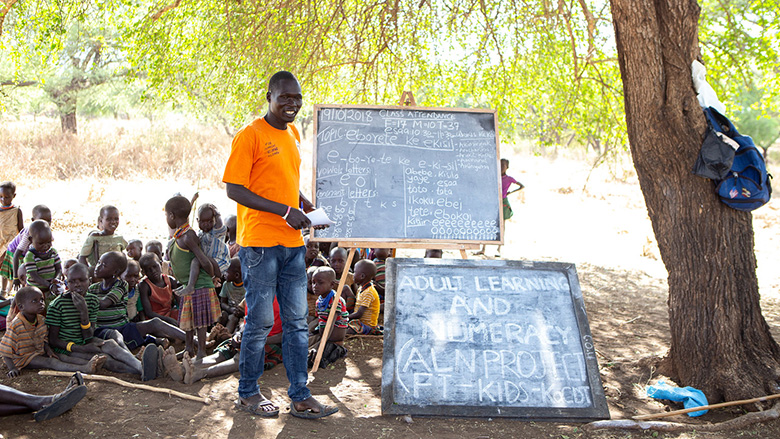

Hannah explains that training has also proved very successful in areas that experience conflict such as South Sudan. Those communities and groups often have to physically move to another town so equipping them with the training early on has been vital.

“Because they within themselves have the knowledge of how to run the group and they are able to move and then continue somewhere else,” said Hannah. “So we find that they do that so I think for us we see that as being those kinds of contexts as being our focus and where what we do can really add value.”

By empowering members through education and training, Five Talents are trying to enable individuals to mobilise and take ownership over their own finances and earning potential even if they are displaced by conflict. Helping to avoid dependence on charities.

Lydia explains that with almost all of their training programmes they always try to put a gender lens on it.

“The way we may view money might be slightly different from how men view it,” she said. “So in terms of the topics, they might be the same but how it is delivered and examples and the case studies that are used just to make it more context-specific for them.”

Sally explains that the focus on women has always been intentional. She refers to the belief that that the face of poverty is a female face. That the training is essential for women, who make up 74% of all microfinance clients.

“We believe that the money that we’re giving to the women are just the catalyst, it is the training, the network systems and the support system that we put in place that really helped them to use the money effectively,” said Lydia.

Lydia explains that as women are often late adopters of technology (reference), so have been pairing their training with phones they give to the women.

“We realises that not all of the women do have access to mobile phones, especially those in rural communities,” said Lydia. “So one of the things that opportunity have been trying to do for the past few months or a year is to help those who may have no phones so we’ve been providing them with basic phones so that they can also use it for financial transactions.”

They also train the women as ‘pre-educators’ to help other women in their communities.

“Within the community, we have people we call community ambassadors. So they are basically women that are like community leaders,” said Lydia. “We trained them how to deliver this training so that if a woman is trying to make any transaction using their phone, and they get stuck, they can go and ask questions or ask for help.”

This has been successful for Opportunity as it allows them to make the communities self-sustaining.

Lydia also explains that when it comes to working with communities they always rely on local expertise. If there is an issue with gender violence, land ownership, or training that they want to do, they always rely on the local ‘policy makers’ within the community.

“We can approach them to support us, so those partnerships, I think, and are very critical in terms of whether it will be successful or not within the communities that we work in,” she said.

She further acknowledges that whilst Opportunity focuses on the financial side these strategic partners bring so much to their operations.

“We know that we are good and best on the finance side,” said Lydia. “But we are not on the business or working with farmers in terms of providing the technical know-how on how they can plant their crops and maybe maximise their production, or we don’t know how to link them up with markets.”

Hannah also explained that Five Talents found that giving more of the governance to local partners allowed them greater ability to provide financial education. They found before that often the pressures on an organisation that is managing a microfinance portfolio meant that the time that could be dedicated to training was reduced.

“What we’re saying through our approach to people is actually you can do this, you can manage this let us support you but you will be leading this and that’s a very different approach to one of a more traditional microfinance organisation where somebody saves in and they’re money is managed and the rules are set and it’s much more customer-client relationship,” said Hannah.

Combining financial literacy training and microfinance may not lift everyone out of poverty like the hope was at the beginning of the century. However, it may see a new generation of financially literate people begin to grow in the developing world.

“The potential is not poverty alleviation, the potential is one toolset toward making people have a better ability to manage their financial lives,” said Todd. “And that’s really valuable to people, even if it’s not helping them completely escape poverty, but managing financial ups and downs in their daily lives and the flow of cash in and out and the ability to get some assurance and the ability to put money away for your retirement and your kids’ education.