Cancer patients from ethnic minority communities face stark inequalities in medical care and treatment. What is alienating these communities from getting the care they need?

Shoaib beamed when he saw his wife with the tiffin. As a lung cancer patient admitted to the hospital for treatment, home-cooked food was one of the very few things that lifted his spirits. Ayesha opened the box to serve him his favourite biryani. She was not expecting a firm tap on her shoulder.

“You cannot have this food here,” said the nurse. “The other patients find the smell annoying. Also, can you please speak in English and not in your native tongue? It is making the patient on the next bed uncomfortable.”

This is an all-too-common experience for cancer patients from the South Asian community, according to Ali Orhan, the CEO of Cancer Equality, a platform to raise awareness about the health inequalities faced by minority ethnic communities in cancer treatment.

“It is ridiculous that your nutritional intake is dependent on someone else’s preference for a certain smell,” says Ali. “And when you are dealing with an issue like cancer, with grave illness and mortality, you don’t have the strength to protest. You are at the mercy of the system. You do as you are told.”

Over the years, the National Cancer Patient experience survey has consistently shown lower scores in cancer care experience for people from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups as compared to white groups. A recent study has also found that Black and Asian people have to wait longer for a cancer diagnosis compared to white people which affects their treatment options and odds of survival.

According to Ali, this can be due to multiple factors including a lack of understanding of diverse cultures, unconscious bias, or even active racial discrimination.

“If you have a deep-rooted dislike or bias for a certain community, regardless of what you do, it will reflect in your work, it will manifest itself,” says Ali. “Those at the receiving end of discrimination experience it in all forms, be it the hospital or the streets.”

Ali founded Cancer Equality in 1999 with a group of experts in the field of cancer care, information, and support to raise awareness about cancer within minority ethnic communities and address the issue of inequality in cancer care by helping support organisations deliver culturally appropriate services.

“I was seeing people in our communities dying of ignorance,” says Ali. “And that was not acceptable. We don’t want to solely criticize the service providers for not doing enough. We want to challenge our own communities as well.”

One of their most far-reaching campaigns has been the introduction of Ethnic Minority Cancer Awareness month in July to bring to notice the plight of cancer patients from ethnic minority communities. The campaign allows mainstream services to use the month as a platform to promote the services they offer to these particular communities.

The month is also aimed at addressing the issue of treating cancer as a taboo in many of the minority communities in the UK and fostering discussion about what prevents people in the community from accessing healthcare in a timely manner.

“With ethnic minority cancer patients, it’s usually at the point of crisis when cancer is diagnosed,” says Ali. “People avoid even talking about it, and it’s as if you utter those words, it will arrive at your doorstep. There is both ignorance and superstition.”

Ali says that there are many reasons behind the community’s lax attitude towards the disease. Health and well-being within minority ethnic communities are treated as somewhat secondary. But racism and poverty are among the major driving forces behind this apparent neglect.

People from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic households were over twice as likely to live in poverty compared to white people according to a study done by Social Metrics Commission in 2020. This had left these ethnicities more vulnerable to job losses and pay cuts, especially during the pandemic.

“When you are facing discrimination and racism, you are in poor housing, working on zero contract hours, you can’t afford to take time off work to go see your doctor,” says Ali. “How can health be a priority in such circumstances?”

I have seen people in our communities die in horrendous situations at home, not having access to services and care that they needed,

Ali orhan

According to Ali, there is also a lack of assistance for minority ethnic cancer patients from mainstream cancer support that frequently fall short of adapting their messages and awareness campaigns to fit the needs of specific communities. Campaigns often use a one size fits all model which fails to recognize cultural differences and sensibilities.

“They might put up a black face or a brown face in the campaign but the messaging, the language, how the message is conveyed, in most instances alienates the community because there is no thought behind it.”

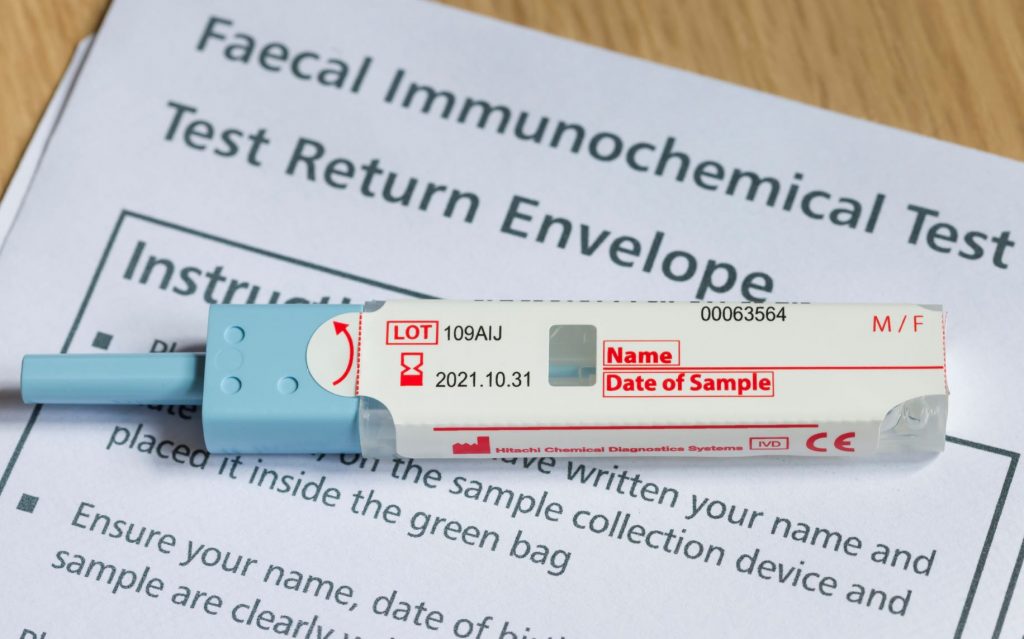

The bowel cancer screening campaign, for instance, has had a low rate of engagement from the South Asian community. Bowel cancer is one of the most common cancers in the UK. Home testing kits are available for people aged 56 to 74 and test the presence of blood in the stool. The test requires collecting and sending a small quantity of stool to the lab which is then examined for abnormalities.

Studies have shown that there is a lower uptake of bowel screening kits in the South Asian community because of limitations posed by English, the complicated nature of the collection of the sample, which is also seen as a cultural taboo, and reliance on younger family members for translation of the instruction leaflet.

“It would be extremely embarrassing for me if I have to go to my teenage son and ask him to translate and explain to me how to take a stool sample,” says Ali. “Especially in the South Asian community, it is not considered culturally appropriate to have such conversations with your elders.”

The language barrier also significantly affects the treatment experience of people from the South Asian community. Research has found that patients who have limited knowledge of English found it difficult to communicate with the hospital staff and had to depend on informal sources for translating, like friends, family, or bilingual staff.

“There have been cases where young or teenaged kids have been brought to wards to break the news of a cancer diagnosis to their friends or relatives,” says Ali. “How is that appropriate?”

This has more serious consequences in the absence of trained language support and sensitivity to ethnic differences. The Cancer Patient Experience survey also indicates that ethnic minority cancer patients were more likely to say that were not involved in the decision-making regarding their care and also were not adequately explained their treatment options. This prevents the patients from making informed choices about their treatment.

According to Ali, the actual side effects of treatment may also not be clearly explained to the patients and when they experience the adverse effects, they feel like the treatment is not working and then stop the treatment.

There is also good evidence to suggest low uptake of Palliative care and end-of-life services among the BAME community. This is because of factors like lack of referrals, knowledge about these services, religious and spiritual beliefs and insufficient understanding of cultural sensibilities among service providers.

“I have seen people in our communities die in horrendous situations at home, not having access to services and care that they needed,” says Ali. “And in stark contrast, I walk into a hospice, where there are predominantly white people in tranquil, caring environments with the best of support, hygiene, and medication and their life ends relatively much more peacefully.”

Part of it also has to do with the choice that people make of deciding to die at home rather than in a hospice but according to Ali, this is often a decision that can be forced out of a dearth of options rather than free will.

General practitioners in a sample study were shown to be unaware of palliative services that cater to ethnic minorities. Studies have shown that there is a lack of referrals for end-of-life services for many South Asian patients because of the stereotype and assumption that family members would care for the patients because of cultural reasons.

“It should be about informed choice,” says Ali. “I may choose to look after my mother at the end of life and care for her but equally so, I may also want to have a palliative care nurse to attend to her personal needs. When this choice isn’t available, then it’s a problem.”

These multitudes of issues contribute to the high level of health inequalities faced by cancer patients in the BAME communities. A number of consultations have happened in the past regarding the inclusion of these communities but Ali says that most people in the community are reluctant to engage with them as they feel the questionnaires to merely tick-bock exercises with little difference to see on the ground.

“We see all these reports coming out where the ethnic minority communities are involved in questionnaires, focus groups, and panels. But no one looks at the recommendations, no one is taking action on them, no one holds them to account,” says Ali.

He presses on the necessity of consultation and collaborative work with both the community and the mainstream service providers and more proactive discussion about addressing the needs of these people. It is essential to achieve tangible results on ground that would address the health inequalities in cancer care for ethnic minorities.

“The thing about cancer is that we can prove that early detection can save lives,” says Ali. “But if it’s not happening, then, in essence, you are in a way, contributing to a community’s demise.”