Body positivity has faced criticism for centring smaller, able-bodied people. How are influencers counter-acting this, and are algorithms standing in their way?

Flicking through the latest publication of Vogue magazine, Rachel admires the beauty of the models posed across the pages. Although she adores the bold editorials and takes inspiration for her own writing, she feels discouraged, because as a disabled girl no one looks like her.

So Rachel takes matters into her own hands. At 15, she set up her own blog where she talks about body positivity and fashion, just the same as the mainstream magazines were doing.

Now 27, Rachel Jeffery, an influencer and writer, has built up a platform that centres around disabled people. “I started so the next generation of 10 year old disabled girls don’t have to go through what I did in terms of isolation and being misunderstood,” says Rachel. “That was a really huge driving force. I just want to give disabled women a lot of confidence.”

Rachel was born with Spastic Quadriplegic Cerebral Palsy and Dystonia and uses a wheelchair. Her blog alongside her Instagram account under the name ‘Disabled Dahling’ started as an outlet to share her day to day life. “I’ve created this alter ego for online, where I feel like I’m able to talk more about my experiences because even though I’m talking about me, I’m putting them across as this fabulous woman,” says Rachel.

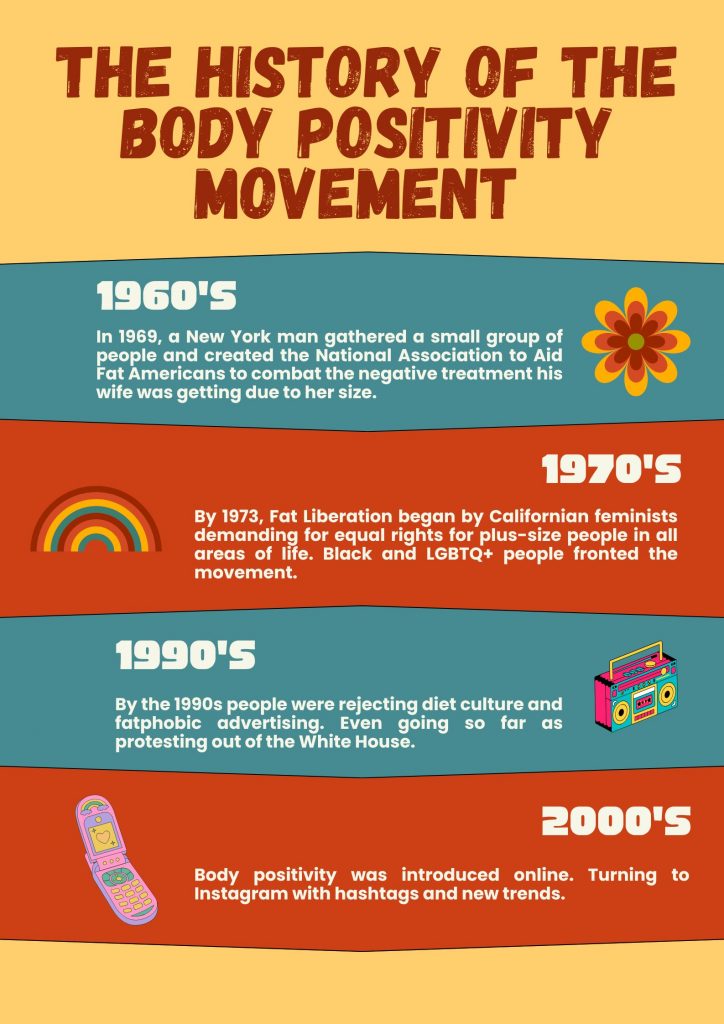

Her advocacy work online is part of a wider movement of body positivity, one that stems from radical roots. In 1960s America, the fat acceptance campaign began to fight back against the treatment of plus-size people. Black, plus-size women were at the heart of the movement, standing up for marginalised groups who were often discriminated against because of their looks.

In recent times, the body positivity movement on social media has been diluted by people with smaller bodies. Stephanie Yeboah, a body positive content creator and author writes extensively about this. In one blog post she says, “the current body positivity movement has been co-opted by privileged bodies, who have implemented their own beauty standards that have excluded the very marginalised bodies that created it in the first place.”

For disabled influencers, creating their own positive space on social media is crucial. Bee Gibson, a 28 year old content creator, first started their account to connect with people similar to them. “I began to build a community with other disabled, chronically ill, fat and queer people and for the first time in my life, I felt I truly belonged to a bigger purpose.”

Bee initially felt accepted by the movement but this did not last as her body changed. “As I gained more weight and became a larger fat [person], I felt less included,” says Bee. “I felt like there wasn’t a space for my bigger body, as much as there was for my smaller fat body.”

While the body positivity movement claims to include all body types, there seems to be a limit. Larger plus size women who are meant to be celebrated face rejection and society pushes them to the sidelines.

This expands to more than exclusion. Bee has noticed that over time their content performs differently, with little attention paid to their conversations about their disability. “I also felt like people didn’t really want to hear about my experiences with chronic illness and disability. I’d gain more traction posting in lingerie, than I did talking about the struggles of Fibromyalgia.”

Many disabled content creators feel that their posts are suppressed on social media. This is increasingly becoming a debate between platforms and users.

Rachel feels frustrated by the lack of diversity online. “There’s no sort of variation of body types or even disability on the algorithm. It very much promotes ableism, that able bodies are more important and have more value on social media than disabled bodies do,” says Rachel. “When it’s not all about looks, it’s more about experiences that you can share.”

Dr Olivia Banner, a former Associate Professor in Critical Media Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas explains that algorithms are built within ableist contexts. “This doesn’t happen because an algorithm has been crafted ‘to be ableist,’ says Olivia. “It happens because of the contexts in which algorithms are developed and instituted already favour able-bodiedness and cultures of ability.”

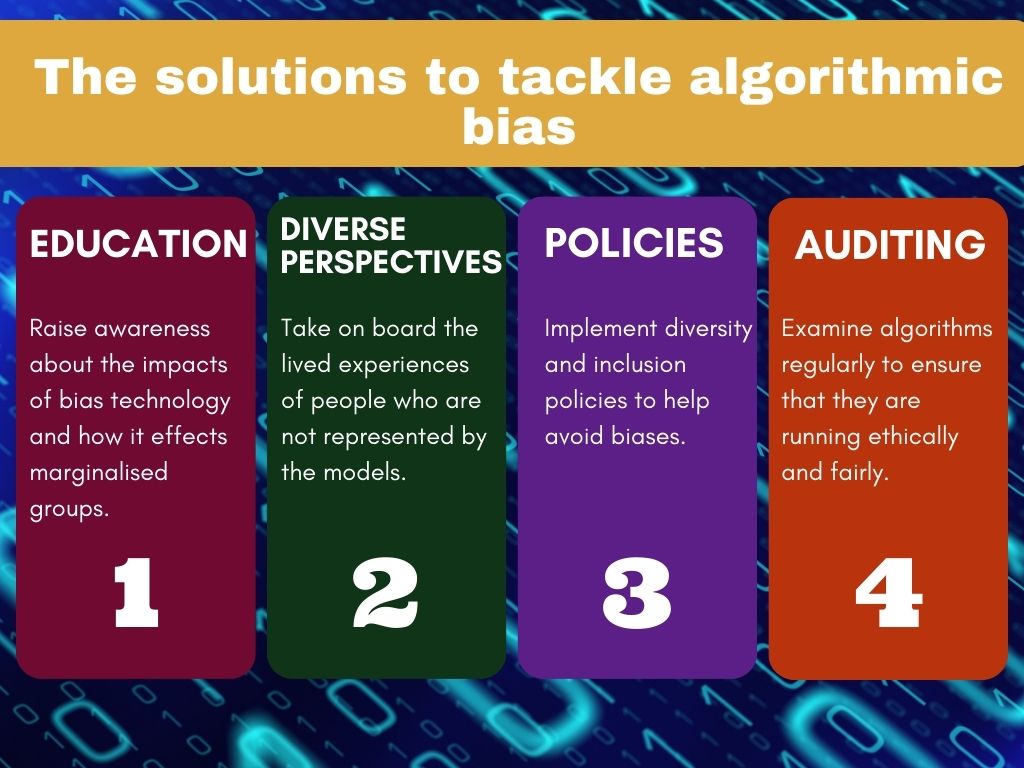

Aditya Vashistha, an Assistant Professor in Computing and Information Science at Cornell University believes that algorithms can be biased by design, favouring certain groups of people. “When you train an algorithm, you have to make very intentional decisions on who is included and who is not. You certainly may have a priority of where the data is going to be collected first,” says Aditya. “It’s just how the economic incentives of social media platforms are and who they align with, and those are the people who are represented in these systems.”

Influencers feel the effect of this. Rachel witnesses her content as well as other creator’s content getting taken down for sharing parts of their disability. From displaying a catheter bag or a stoma bag, simply talking about their health can result in platforms flagging their posts for nudity.

Mostly, it just felt like my body was being censored, or deemed wrong just on the basis of it being visible. – Bee

Bee also faces a similar problem. After posting a set of lingerie photos they noticed that the post had been removed. This still frustrates them as they see other influencers do this without repercussions. “This kind of content isn’t typically removed when posted by straight-size content creators,” says Bee. “Mostly, it just felt like my body was being censored, or deemed wrong just on the basis of it being visible.”

Algorithms can do more than remove posts, platforms can limit the reach of marginalised creators content. TikTok has admitted to doing this by censoring disabled, plus size, and LGBTQ+ user’s videos as an attempt to control bullying on the app.

This meant their content could not reach other countries and it kept them from the ‘For You’ page, which is the gateway to visibility, after hitting a certain number of views.

TikTok responded with this statement. “Early on, in response to an increase in bullying on the app, we implemented a blunt and temporary policy. While the intention was good, the approach was wrong and we have long since changed the earlier policy in favour of more nuanced anti-bullying policies and in-app protections.”

Instagram has also made headlines in the past following claims that they removed plus-size women’s posts. In 2020, Nyome Nicholas-Williams, a Black, plus-size model posted a photo of herself topless with her arms wrapped around her body to cover herself. Hours later Instagram removed her post.

The hashtag ‘I want to see Nyome’ started trending as many people also tried to upload the photo and it continued to be deleted. Following accusations that the platform was racist and fatphobic, Instagram apologised and Nyome was able to repost her photo.

The same year, the CEO of Instagram, Adam Mosseri took to the platform to talk about the need to look into algorithmic bias after claims were made about Instagram suppressing marginalised voices. In the post he wrote, “words are not enough. That’s why we’re committed to looking at the ways our policies, tools and processes impact black people and other under-represented groups on Instagram.”

Meta, who owns Instagram, have stated that they are working on getting rid of biases and unfairness but some remain sceptical.

Algorithm biases can affect the visibility of disabled creator’s posts but it can also shape the kind of abuse content creators face online.

Aditya researches the impact of technology on disabled people and has noticed that online abuse can go under the radar because algorithms are not set up to fully comprehend ableism. “If you look at toxicity classifiers and language models, which form as the backbone of content moderation platforms, which many of these social media platforms use, then we have seen, through our work, how they do not really understand the nuances of ableism and how they really do not match with how people with disabilities feel about ableist content,” says Aditya. “Most of the toxicity classifiers don’t have a specific category for disability.”

Rachel deals with negative comments that often go unchecked. From comments about her body, to her catheter bag and even her advocacy work, particularly about her stance on the disability benefit cuts. And sometimes Rachel struggles to cope with the hate. “I do cry. That is my first reaction to anything. I get overstimulated quite easily, so I cry mostly out of frustration that people don’t understand where I’m coming from,” says Rachel.

Rachel is not alone. Almost 50% of disabled people have witnessed negative comments about their condition, according to Scope.

Beyond online hate, content creators face pressure and expectations to keep up with their public platform. Just over 50% of influencers say they have experienced burnout as a direct result of their career, according to a survey by Billion Dollar Boy, a social agency.

For some, it can all get too much. Bee has recently stepped back from their social media accounts because of the struggles of keeping up with the demands of posting online. “I started experiencing burnout which I think is an issue for all creators, but especially when your body already has limited energy and capacity. I was experiencing burnout from what felt like to be shouting into the void, and also because my body was just struggling to have the energy to do much of anything,” says Bee.

Content creators themselves can also struggle with their own body image. This has been the case for Bee and is another reason why they have taken a step back from posting online.

At times, Rachel feels the same. “It does affect the way I see my body because I think, ‘oh my God I shouldn’t wear clothes like that,” and “I’m never going to find anybody that’s going to love my body.”

But Rachel has started to make peace with her appearance. “I’ve started eating healthier, and treating my body with a lot more respect,” says Rachel.

Sometimes Bee feels unsure whether to discuss their health online out of fear of judgement. ”Disabled fat creators are also consistently hidden and not permitted a place,” says Bee. “It’s difficult to talk about disability as a fat person because our disabilities are seen as our fault for not treating our body well enough, our bodies are wrong, and our illnesses and disabilities are collateral damage.”

Rachel is continuing to do advocacy work on her platforms. She regularly posts uplifting content, celebrating her body and pushing others to do the same. Rachel has built a community, one that helps them as much as it helps her. “I like to think of people who follow me as my friends. So I talk to them about things I would talk to my friends about,” says Rachel.

Rachel’s advocacy work is recognised. She is now an ambassador for Accessify UK, a think tank for accessible living. Working for Accessify is a huge milestone for Rachel, giving her the opportunity to get involved in coordinating their social media.

Inclusivity is not about being inspirational, for Rachel it is about creating a community to celebrate disabled people, breaking stereotypes, and making her voice heard.

‘Inspiration porn,’ a term coined by comedian and Disability Advocate Stella Young, refers to the objectification of disabled people. This is frustrating for Rachel who is trying to get on with her day to day life. People will say to her, “Oh my God, ‘you’re so inspirational for getting the train on your own’ and those sort of trivial things, and you just cringe and you think, I’m just trying to do my every day mate. It’s nothing different to what anybody else would do,” says Rachel.

Advocating for diversity and the inclusion of disabled people in the body positivity movement is Rachel’s priority. Rachel always makes sure to put disabled people’s interests first. “It is harder for disabled individuals because there are people that are constantly looking for inspirational content, wanting you to make able bodied people feel better about themselves when that’s not what you are doing. Your focus is on your other disabled comrades,” says Rachel. “More than anything, I’m happy to talk about body positivity with anybody, able bodied or disabled, but my main focus is always going to be my disabled community because I feel that’s where it’s lacking.”