When teachers in a Birmingham school used stories with LGBT characters in the classroom, protesters quickly started to gather. So why do kids’ storybooks cause so much conflict? We talk to authors of these stories to find out why they think it’s important to tell these tales.

It is a normal school day. In a classroom, young pupils are listening to their teacher carefully, but from time to time, there are noises coming through the window. The teacher in the front, raises her voice a little to help children focus on the lesson, but she looks a bit worried.

Outside the school, hundreds of campaigners are gathering together. Holding signs such as “Let kids be kids” and “Say no to sexualisation of children”, angry parents and activists are protesting against a primary school project, No Outsiders, saying that the teaching about LGBT equality involved contradicts their religious belief and is age inappropriate.

Starting from the Parkfield school in January 2019, the LGBT teaching protests had spread to several schools in Birmingham within months. “There’s a lot of misinformation and rumours about what No Outsiders was,” said Andrew Moffat, creator of the No Outsiders project and assistant head teacher at Parkfield Community School. “People were saying it was LGBT lessons, it was teaching children to be transgender, teaching children to be gay. And it’s none of those things.”

No Outsiders, according to Andrew, uses a collection of picture books to teach children equality and diversity, including LGBT, disability and race. “No Outsiders teaches children that we are all different, but we can all get along. It prepares children for life as global citizens.” said Andrew, who believes children need to work and live anywhere if they grow up and need to know that the world is full of different people.

Andrew used to work on the emotional literacy and teach children about different feelings by using picture books. With the experience that storytelling is a good way of talking to kids on difficult issues, he created the No Outsiders project in 2014, with a series of children’s books on diversity and equality included.

Andrew believes many books can be used to talk about LGBT equality. Some books that he uses involves LGBT characters, such as Mummy Mama and Me. Some books do not contain any of those character, but about diversity and difference, such as This Is Our House, where LGBT can be brought in context. Andrew said, the way of using stories made equality very simple for primary schools. “You base on picture books, so it is simple and non-threatening, and it just works,” said he.

Children’s stories related with LGBT issues have always been controversial. Heather Has Two Mummies, written by Lesléa Newman and first published in 1989, tells a story of a little girl and her two lesbian mums. Being regarded as one of the first pieces of LGBT children’s literature, the book caused huge debate and was ranked as the 9th most frequently challenged book by the American Library Association in the 1990s.

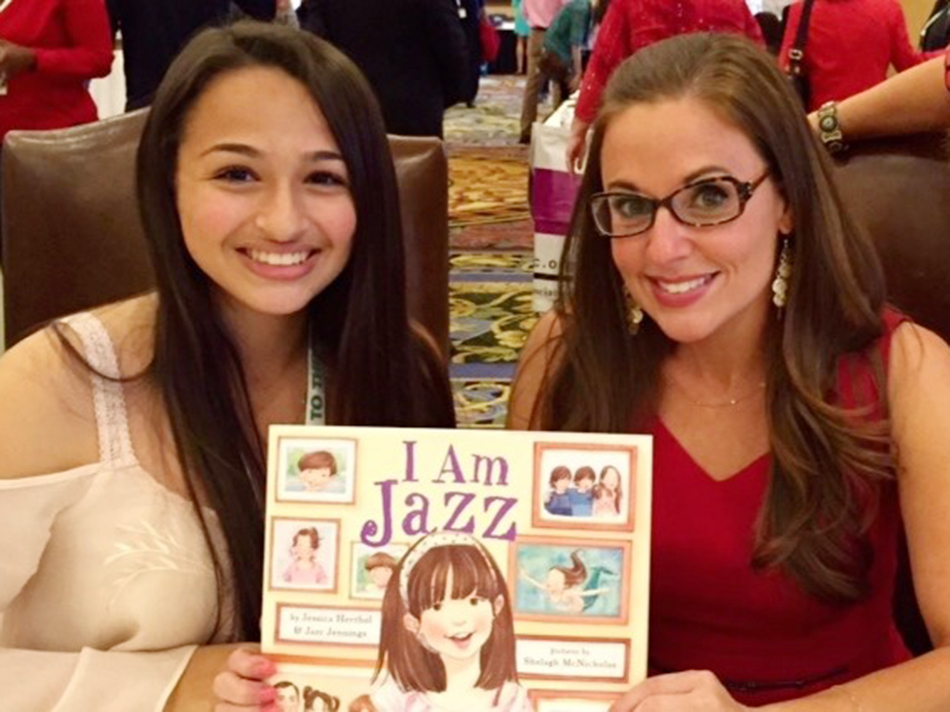

I Am Jazz, written by Jessica Herthel is another example. It tells a story about a transgender girl based on the real-life experience and was published in 2014. While in 2015, it was ranked as the top 3 of the most challenged books by the American Library Association and has been on the list for several years.

According to the Guardian, the attempt to remove books from US libraries increased 17% in 2019, with children’s books LGBTQ including characters as 80% of the most challenged books on the annual list by the American Library Association.

Lesléa said, she wrote the book Heather Has Two Mommies, due to a request of a lesbian mum from a two mum-family, who couldn’t find a book for her daughter to show their life. Although the book has got a lot of feedback both positive and negative, she believes, it is of great significance for all kids.

“It is important for children who have a family like Heather’s to see themselves reflected in a children’s book, which is a very validating experience. And it is important for children who have a family unlike Heather’s to learn that there are all types of families in the world,” said Lesléa, 64-year-old author of more than 75 books.

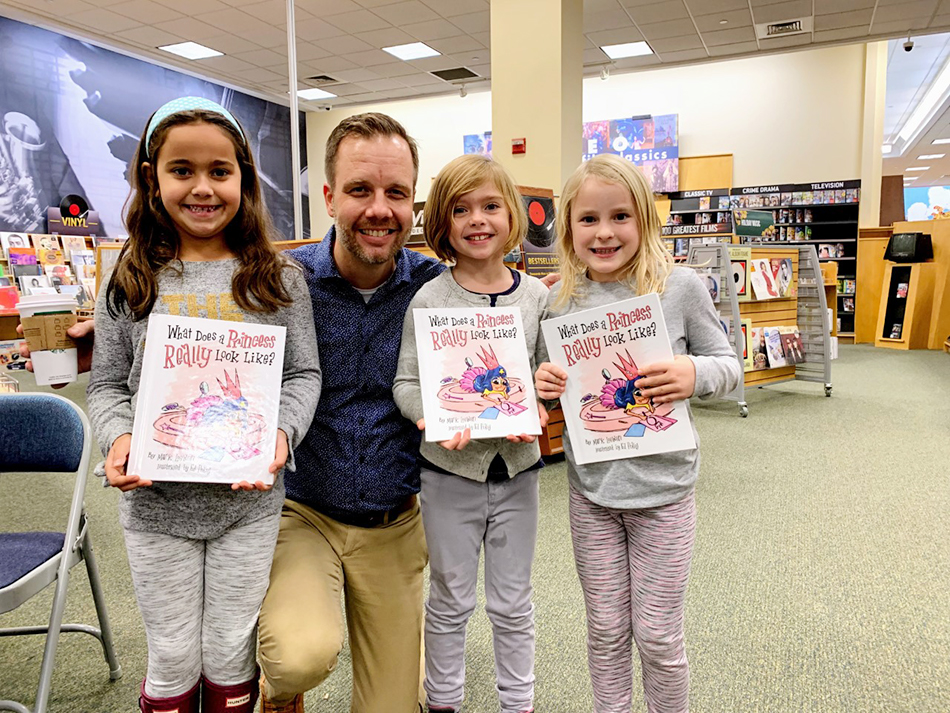

Mark Loewen, author of What Does a Princess Really Look Like, believes books with LGBT characters are mirrors for children who have a relationship to it, either it’s with LGBT parents or about themselves. And the reason for him to write the book was because he wanted his daughter Zoe to see her own family.

Eight years ago, Zoe was openly adopted by Mark and his husband just after she was born. One day when she was age 2, she sat on a sofa with the two dads and read the book And Tango Makes Three. Page by page, when seeing the picture where two parent penguins and baby penguin swim together, she lit up and said: “Dady, Papa, Zoe!”

“She finally saw her family,” said Mark, the 40-year-old author and mental health therapist. Believing that everything needs to be talked about, Mark said, with Zoe, they had talked a lot and had books from very early on. “At that point, we bought all the books we could find about two dads, so that was something that she had always seen and been open about,” added he.

When Zoe was little, she always introduced herself happily that she’s Zoe, adopted and has two fathers. “That was her thing. That was part of them that she felt to make her special,” said Mark. But as growing up, things changed a little bit.

“I think some of the challenges for her started when she was in kindergarten,” said Mark. At that time, kids started asking and saying to Zoe that she couldn’t have two dads, or two dads couldn’t be a family. Mark said, all those words made Zoe question a lot, and as she was adopted, the hurt was doubled.

The situation got even worse after Zoe entered the primary school. Mark said, in kindergarten, kids asked a little bit, but it was in the first grade when the questions became more and more intense. One night, Zoe got back home and cried: “I’m so tired of kids who don’t know about anything.”

Marks believes, sometimes people don’t understand, because they just don’t know, and those kids who kept asking Zoe difficult questions were not trying to be mean, but they were just trying to understand it. “It’s hard for children to understand,” said Mark.

In 2018, Mark published a children’s book, What Does a Princess Really Look like, with a girl who has two dads, discovering that being a princess is more about courage, determination and kindness in heart.

According to him, books about families with two mums or two dads are normally placed in a special section, but more kids and their families just go to “the main area”. Therefore, if in a story, a family just happens to be diverse, it will go to “the main area” and other kids that don’t have two mums or two dads can also see it.

“A lot of kids just don’t have the access to these families,” said Mark, who believes much frustration happened on Zoe was due to the lack of awareness and understanding. “We can’t all know or meet all different families.”

Apart from helping to understand diverse families, Mark thinks the gay dads and gay mums in children’s books are of great significance for gay children. “[They] are a very good and developmentally appropriate way to show it to the children, for children to see even the sex orientation can be different,” said he. “It gives children also something to project themselves. Like they know, if they ever are gay, they can [also] have a family.”

Mark believes books helps everyone and they have so much power. “When you read a book about somebody, you’re not arguing with them. You’re just listening what this experience is, and you’re just open to learning whatever happens with the character and the book,” said he. “In that way, it helps us to see other people’s experience and it opens us up to possibilities and to create possibilities.”

There is a famous saying by Rudine Sims Bishop, that books are windows to a different life, and mirrors to see ourselves, and Jessica Herthel, author of the controversial children’s book, I Am Jazz, said it was also the reason why children’s books featuring LGBT characters were very important.

“When you’re in school and the teacher is teaching, and you don’t see yourself in any of the books that are being taught, it makes you feel invisible,” said Jessica, the 45-year-old author. And children’s books that has LGBT characters, according to her, validate the kids in the classroom, who might be the only gay or trans kid in their class, or maybe in their school, which could be very lonely.

Jessica met Jazz, a transgender girl in their community, when her youngest daughter was 4 years old. She introduced Jazz to her with simple words, much in the same way of teaching her to not judge disabled people by the shape of their bodies: “I’m going to introduce you a kid who also has an interesting shape. She was born in the shape of a boy, but she’s just like you.”

“That’s all I needed to say for my littlest child to accept what transgender means, and just move pass it and get to know Jazz as a person and not a trans person,” said Jessica, who believes adults tend to complicate things, while for kids, it can simpler.

Jessica said, many of her friends were nervous about talking to their kids about anything that was related with LGBT, and they felt it developmentally inappropriate to talk to little kids, or afraid of saying the wrong thing. However, she believed that little kids could understand these concepts if they were provided with age appropriate information.

Jessica turned her idea into a story: I am Jazz in 2014. According to her, it was the first time that the word “transgender” had been used in children’s books, and it was a turning point of the trust that believing children could handle this concept and learn a new word, if adults could give it to them in the text of education and compassion.

However, the book caused huge debate. With many anti-voices, it has been listed as one of the most challenged books by the American Library Association almost every year since being published.

“People are still very scared about things that they don’t know and unfamiliar to them,” said Jessica, who thinks there is a lot of fear around LGBT issues. “There is fear that the more kids know about these topics, the more likely they would become gay and trans, so there is an instinct in certain communities or certain religious communities to just get rid of the books,”said Jessica.

Except for fear, Mark believes the disagreement on what sexual orientation is and how it is formed is the main reason for the debate on children’s books involving LGBT issues. “People who are against it, they think that sexual orientation is a choice, and that if you read the books and you’ll think it really cool, and you’ll become gay,” said Mark. “But it’s not really how science showing us how it works.”

There are also voices that books with LGBT characters are not age appropriate, and Jessica thinks it is due to misunderstanding. She said: “They assume that we are talking to really little kids about sex, but we’re not.” According to her, some people regards anything that is LGBT related as a mature topic, but if they really read those books, they will understand.

Mark agreed that age was not a reason for LGBT being limited in children’s books. He believes, rather than the topic, the developmental level is the factor to consider. “[LGBT] is not a bad thing, but look at what the developmental level is appropriate, just like to teach straight people,” said Mark.

Jessica thinks religion is another factor for the anti-voices. According to her, some religious people are raised to believe that god does not like gay people, and that trans people are made up because god does not make mistakes. And if they are raised to believe that gay and trans people are doing something wrong in the eyes of their religion, it’s very scary and destabilising for their worldview to meet someone who say proudly that they are gay or trans.

“Because on the one hand you were told from a young age that this was bad, and yet here is someone acting as if it is good and something to be proud of,” added her.

Although LGBT is very controversial in children’s books, Jessica believes it is better to give kids the language to understand these concepts. “When you don’t talk to little kids about these issues, you risk that some of these children who are struggling are going to struggle in silence for years,” said Jessica. “And their rates of self-harm are off the charts, and they attempt to suicide and anxiety and depression.”

Mental Health Foundation says, LGBT people are at a higher risk of experiencing mental health problems such as depression, suicidal thoughts and self-harm. And based on a research over last 40 years, the suicide attempts of LGBT youth can be between 4 and 7 times that of heterosexual and cisgender young people, according to Queer Features.

“The children who are most at risk for self-harm are those who feel misunderstood and alone in the world,” said Jessica. Therefore, she would prefer having many conversations rather than not having enough of them, in the way of telling kids that they are fine just the way they are.

We live in a world formed by a range of various people. Mark said: “I hope that we can grow to really enjoy other people’s and our differences.”He wishes people can be more curious about the world and understand that somebody else can have experiences that are very different from ours, and just because of the difference, it doesn’t mean that it’s not true.

The Birmingham teaching protests gradually faded away due to a decision made by a High Court judge that demonstrations against LGBT inclusive education were permanently banned around Anderton Park, where campaigners had gathered to protest for months.

Andrew said, after learning the stories in No Outsiders project, he saw children confident about diversity and difference, and the bullying situation also improved in the school. He said: “There is no doubt that if you teach children a consistent message about diversity being a good thing, then children become less judgmental and more comfortable around difference.”

Just like the name of the project, Andrew has a best wish for all children in the school. “My hope is that children will grow up knowing that in school they are insided, and insided with more tolerance or difference, and therefore more excepting of everyone, and everyone knows that they are belonging.”

Find more information on No Outsiders project at: https://no-outsiders.com/