In the six months since the outbreak of COVID-19, how did millennials, the group with the highest debt ratio in China, survive this unexpected economic slump, and what did the government do to help?

Long Chen glimpsed at the sex toys lying in the box prepared for customers that hadn’t been used for months. His work involved physical contact with clients and after COVID-19’s outbreak in Wuhan and its subsequent spread across the country, it was hard to operate his business.

Handling his mortgage and other essential living expenses, which accounted for nearly half of his total income, he could only pay off his debts by using his savings and borrowing money from his friends.

During the past three months when the epidemic was at its worst in China, he felt the tremendous pressure brought about by an uncertain future. “You don’t know how long this situation will last. If it continues for one year, I may fail to pay my mortgage, which is around 100,000 RMB, around £11,145”, said Long Chen.

Chen is a 28-year-old from an underprivileged rural area in Haikou. When he finished his secondary school, he came to Shenzhen as unskilled worker in Foxconn, a supplier of Apple merchandise. Later, he became a masseur and sometimes provided sexual services to customers. After several years of hard work, he eventually saved enough money to buy a home in his hometown in Haikou in 2015.

Just before April, when the pandemic in China was not yet fully contained, his family’s agricultural products were not selling, even when offered at half price. When he encountered financial pressure, there was little help to be found.

Long Chen is just one of those millennials who were not prepared to deal with this type of crisis. His particular generation, with their characteristics, are more vulnerable when faced with a disaster like COVID-19.

Unlike their thrifty parents who tend to save and are accustomed to challenging economic and social times, the 415 million millennials born in the 80s and 90s are more liberal when it comes to consumption and they are willing to spend a large percentage of their wages on entertainment, health products, food and travel.

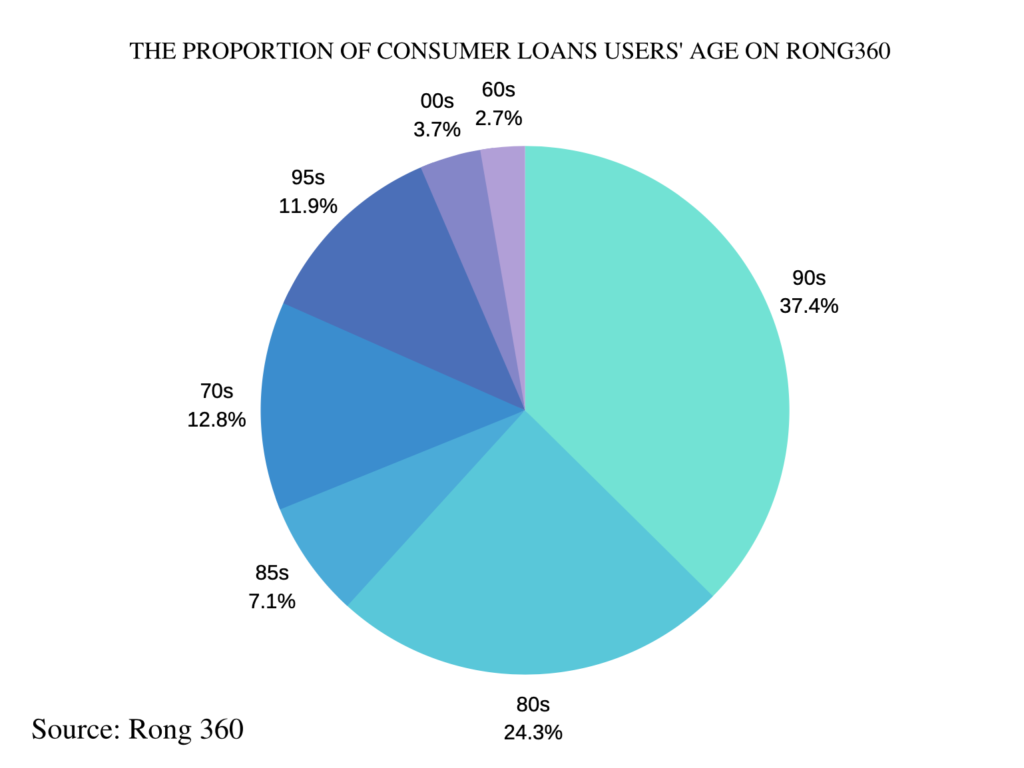

A survey by Rong 360, a US-listed Chinese financial lending platform, shows that around 85 per cent of consumer loan customers were born in the 1980s. Among them, the post-90s and post-95s, are the dominant force regarding consumer loans, and they account for 49.31 per cent.

The tendency to consume excessively raises concerns. Around 49.14 per cent of people’s monthly repayment amounts, excluding mortgages and car loans, account for more than 30 per cent of their actual income.

Dajie Tang, director of the Research Department of the Saiyi Enterprise Research Institute, believes that these individuals may eventually become the group with the highest debt ratio in China.

Expanding domestic demand has helped China alleviate its economic difficulties.

There are three factors that drive China’s economy: investment, export and consumption. In the past, Beijing has relied on investment and exports, which enabled the nation’s economy to achieve rapid development. However, after the investment-driven economic growth slowed and heavy tariffs were imposed by Trump in 2018, China’s economic growth started relying on domestic consumption.

With the global economic recession, brought about by COVID-19, Zhang Dong, a professor at Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, School of Finance, expressed his concerns with regard to these millennials having excessive debt ratios, especially those with high mortgages.

“For individuals, it will cause family financial crises and lower their living standards”, said Professor Zhang, even though “banks usually control the monthly repayments to amount to no more than half of household expenditures.”

I can do nothing but keep myself from being fired and cut down somewhat on our living expenses. This is a hurdle caused by an unexpected epidemic, and you can’t blame anyone

Baixiu ye

Baixiu Ye, a 33-year-old accountant in a state-based company, bought his flat in Shenzhen where the home prices in the city centre ranked eleventh in the world in 2020. He is one of the lucky ones among Shenzhen’s millennials who desire to buy homes.

Without borrowing money from relatives or friends, he and his wife paid the deposit independently, but every month’s mortgage payments account for half of their entire earnings. Last month, his child was born, and the resulting huge additional expenses strained the family budget immeasurably.

“I have been stressed out recently due to COVID-19. Our company has been severely affected, so my expected revenue will definitely decrease. I can do nothing but keep myself from being fired and cut down somewhat on our living expenses. This is a hurdle caused by an unexpected epidemic, and you can’t blame anyone”, said Baixiu Ye.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, the Chinese government has adopted strict lockdown measures to suppress economic activities. In the first quarter, the country suffered a historic setback, a decline of 6.8%, which was China’s largest economic recession since 1992.

At the end of January, the China Banking Regulatory Commission issued a document which stated that those people affected badly by the pandemic could apply for a repayment extension if they temporarily lost their ability to pay off their debts. Consequently, many banks have introduced related policies to mirror this action, such as the Agricultural Bank, and Industrial and Commercial Bank.

Based on the spirit of our nation’s constitution, the property of China belongs to all the people.

Dajie tang

Compared with the practice of directly issuing cash in the UK, the US and Hong Kong, Dajie Tang believed distributing cash was more effective than consumer coupons, especially for those who had been in quarantine for months and had lost income. He suggested that the government could send 2,000 yuan, around £219, in cash to all citizens over the age of 18, a group that currently constitutes about 1.1 billion people.

“Based on the spirit of our nation’s constitution, the property of China belongs to all the people. If the state’s property can be transferred from the government to the people, then this is a practical Chinese dream (Zhong Guo Meng)”, Dajie Tang wrote in an article in March.

Although China’s economy expanded 3.2 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter, according to the officials, the millennials living in cities were still suffering from the economic impact produced by the pandemic.

Xuelin Li, a 33-year-old employee at a safety testing company in Guangzhou, returned to Guangzhou one month after being stuck in his hometown during the Spring Festival and found that he needed to pay twice what he had paid for the same lunch prior to the arrival of COVID-19.

“My salary should have been increased but the opposite happened due to the pandemic, and there was a threat of there being layoffs in the coming months, subject to the company’s monetary intake. I never complained about our firm’s actions and fully understood our leaders’ decisions”, said Xuelin Li.

“But as an outsider in the city, I have to pay my rent and coupled with soaring food prices, I find it difficult to save money, which disturbs me a lot”.

Xuelin’s department mainly serves customers in North America and their orders this year were cut by half when the epidemic in North America went out of control. Whether there will be more orders in the second half of the year, at this point in time, is unknown.

The core of the problem is that the cost of living is so high, and we don’t have enough savings or stable income to continue spending as we did before.

Xuelin li

Sometimes, he used supplied coupons, even though the subsidy of consumer vouchers amounted to little for the individual. On one occasion, Xuelin received a subsidy of no more than 10 yuan, about£1.

“The core of the problem is that the cost of living is so high, and we don’t have enough savings or stable income to continue spending as we did before”, remarked Xuelin Li.

Regarding some difficulties faced by young people today, Qing Xu, an assistant professor at Beijing Normal University, School of Government commented: “For employees or other individuals, dilemmas result from heavy pressure and negatively affect motivation. For the overall development of society, moderate pressure is necessary”.

Faced with uncertain economic prospects, Long Chen intends to save himself by expanding his business, but with a 20-year mortgage hanging over his head, he has a long and arduous journey ahead of him.

Although his work is illegal in China, it is the only job he can do, with his personal background and meagre education, to sustain him and his family. Looking at a bleak future, Long Chen is trying his best to earn more money while he is still young.