As more Chinese volunteers flock to underdeveloped countries to teach, is their arrival really adding value to the Sri Lankan education system?

In a building that looked like an abandoned factory, there were worn-out desks and chairs neatly arranged. A little girl of about ten years old sat on a chair in the corner. And Li Tiange sat next to her, smiling as she watched the girl draw earnestly.

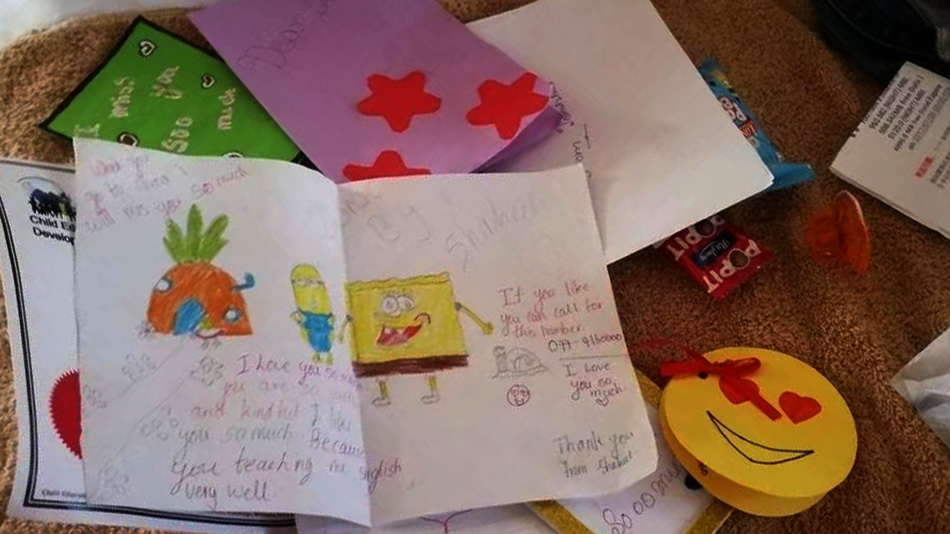

Putting down her crayons, the girl held up her drawing and smiled shyly at Tiange. On the painting were a blue sky, white clouds, flying birds, and a few brightly coloured flowers. “Wow! It is so beautiful,” Tiange said. She gave a thumbs up to show her appreciation, and the girl said “Xiexie” to her, which means thank you in Chinese.

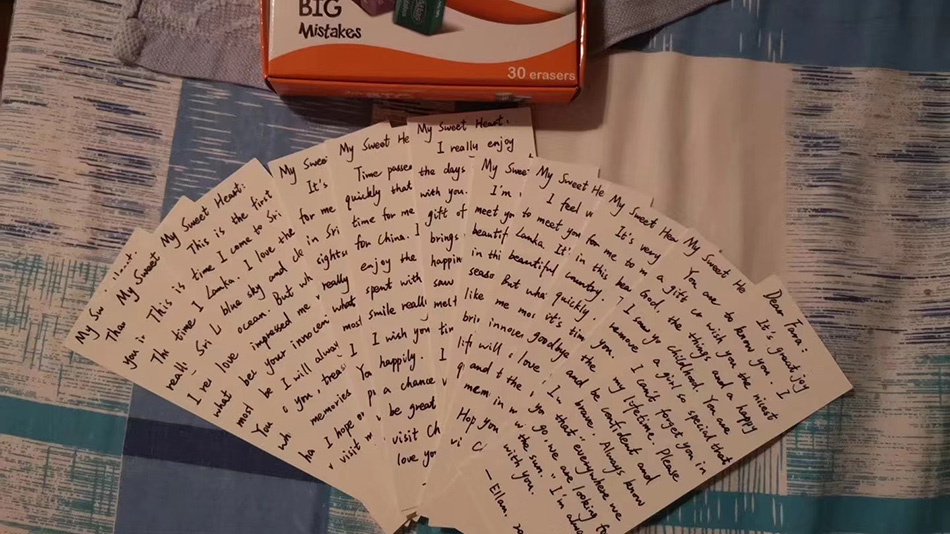

Tiange revels in this memory that belongs to the summer of 2019 when she went to Sri Lanka to volunteer in a primary school and met a girl who has an intellectual disability.

I hope my encouragement will help her become a little more confident and happier

Tiange

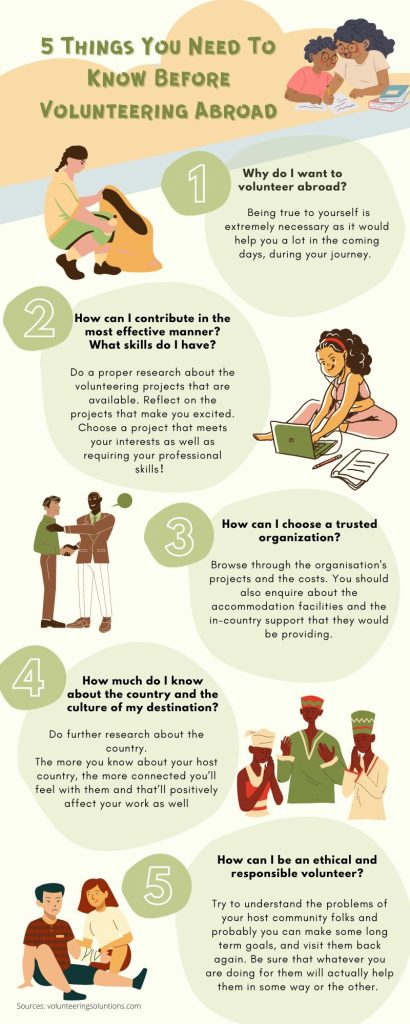

Over the last decade, China’s volunteer tourism sector has grown rapidly. More Chinese young people participate in volunteer tourism. Tiange is one of the many who travel abroad to volunteer in underdeveloped countries.

AISEC is one of the organisations in China that offers overseas volunteer tourism. The organisation is an NGO affiliated with the United Nations Department of Public Information, the world’s largest student organisation. Established in 2002, AISEC China has sent 20,000 Chinese volunteers abroad, according to AIESEC Annual Report (2018-2019).

Chinese volunteer organisations offer projects mostly in Southeast Asian countries, such as Sri Lanka, Cambodia and Nepal. Sri Lanka is one of the most popular ones among Chinese volunteer tourists.

According to Monthly Tourists Arrivals Report 2019 by Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority, 167,863 Chinese tourists arrived in Sri Lanka in 2019, approximately 13% of the total number of visitors to the country that year. The report also reveals that the number of Chinese tourists to Sri Lanka was the most in 2019 among East Asian countries.

In addition to sightseeing tours, some tourists visit Sri Lanka through volunteer tourism. Volunteer projects available to them in the country include teaching, orphanage support and sea turtle rescue activities. And teaching is a classic project for many Chinese volunteer organisations.

It is always easy to find a teaching project in Sri Lanka by clicking on any website of any Chinese volunteer organisation that offers overseas volunteer projects. In project descriptions, organisers often describe Sri Lanka’s beautiful natural landscape as “a tear in the Indian Ocean” or “a country as beautiful as a sapphire”.

Volunteers are usually told by the organisations that Sri Lanka is a beautiful but poor country where the children have nearly no access to quality education. And children need their help.

However, some volunteers involved in the project felt that the volunteer organisations and people from the recipient community did not seem to expect their arrival to make much of an impact on the education system in Sri Lanka. Some volunteers did not even know what they needed to do or could do or what help the children in the recipient communities needed.

I don’t think they even expect us to teach the kids anything. We just bring them a sense of spiritual comfort, give them something, and make them feel like someone cares about them

Tiange

According to the profiles of the teaching projects offered by the volunteer organisations, volunteers shall go to schools in Sri Lanka to teach the children. But, according to Tiange, the role of the Chinese volunteers in Sri Lankan schools is more like that of teaching assistants than teachers.

“We didn’t actually teach the children anything that would help them with their studies. They didn’t let us teach the children any lesson, just a few Chinese children’s songs and a little English,” says Tiange. “It didn’t feel like we played much of a role or taught them anything. Mostly it just makes them feel happy.”

Another volunteer, Yan Xinran, who joined the teaching project with Tiange, said she had never been on the podium to give a lecture when she was volunteering.

“The teacher told us it was okay not to give a lecture,” says Xinran. “I feel like they know you’re only going to stay for a week or two, and then you just leave the country, so they don’t force you.”

In the volunteer teaching project in which Xinran and Tiange participated, the main responsibility for teaching remains with the school teachers, not the volunteers. The volunteers’ job is simply to sit next to the children and then answer questions when they are asked. Outside school hours, the volunteers play with the children and teach them songs.

Not only did the volunteers not take on the role of teachers in the volunteer teaching activities, but they also did not even quite understand the teaching schedule.

Sri Lanka’s recipient schools receive many volunteers from China every year. And Chinese volunteers are usually on short-term projects of one to two weeks. Most schools receive a new batch of volunteers every fortnight.

However, volunteer teachers change frequently, and the handover between each batch of volunteers is haphazard. Sometimes there is not even a handover of volunteer work, according to Xinran. “We know nothing about what the last group of volunteers has taught the children. There was no handover between the previous group of volunteers and us. We just had a simple meal together,” says Xinran.

The lack of handover links leads to duplication of teaching and inefficiencies. For example, one group of volunteers taught the children the famous Chinese song “Jasmine”, and the next group taught the song again. The children learn the same thing over and over again.

Although volunteer tourism was a precious experience for Xinran, she thinks she did not contribute much to this volunteer teaching project.

“I think in the short term, we have reduced the teaching load on teachers. In the long term, it might just give students a chance to interact with foreigners and learn about the outside world,” says Xinran. “This tour made me feel that Sri Lanka is a beautiful country, but I didn’t really feel that I was helping the students much.”

Although for volunteers like Xinran and Tiange, joining a volunteer teaching project is all about tutoring the children and playing games with them. For the people in the recipient community, the volunteers may not just be there to teach and help the students.

Some local teaching staff believes they benefit a lot from Chinese volunteers. Ranganath de Silva, an assistant lecturer at the University of Kelaniya in Sri Lanka who has four-year experience in receiving Chinese volunteer teachers, thinks that Chinese volunteers coming here are really helpful.

“I like Chinese volunteers coming here because it is really helpful to us. We can earn some money for our country. And we can exchange our knowledge, that is the main thing. Also, someone can learn Chinese tradition and the Chinese language. We can also learn from the Chinese education system,” he says.

Ranganath de Silva enjoyed receiving volunteers from China, and it seems to him to be a good and harmless thing to do. “I didn’t see any disadvantages,” he says. “Because the Chinese people will come here and spend some money to buy something. It is good.”

Chinese tourists are always welcome in a country like Sri Lanka that relies heavily on tourism, whether sightseeing or volunteering, as they like to spend money and can contribute greatly to Sri Lanka’s tourism industry.

Ranganath de Silva claims that the arrival of volunteers is good for the country’s economy. According to CEIC data, in 2018, the year before the outbreak of COVID19, Sri Lanka’s total tourism revenue was US$4.38 billion, accounting for 10% of its total GDP. And the country received the most foreign tourists from India, the UK, and China, according to the Monthly Tourist Arrivals Report 2019.

Despite this, Ranganath de Silva suggests that Chinese volunteers still need to do more to really help the country’s education system. He hopes that more volunteers will be able to go to remote rural areas where the students need more help. “If you can go and visit our rural and remote areas, it is the better thing you can do,” he says.

According to Ranganath de Silva, the lack of educational resources in remote rural areas is a significant problem for the country’s education system. Even though education in Sri Lanka is free for all, from kindergarten to university, the country’s educational resources are unevenly distributed due to the wide disparity in regional economic levels.

Few teachers are willing to teach in remote rural areas because of the scarce resources, poor living conditions, and inconvenient transport systems, according to Prashanthi Narangoda, a professor at Kelaniya University, Sri Lanka. She worked with a Chinese volunteer organisation from 2015 to 2019.

However, Chinese volunteers are more likely to teach in international and some public schools, while some schools in genuinely remote areas still desperately need teachers. “They go to actually the big cities, I suppose. And that is why they are stationed in a particular area. To my knowledge, they have not been engaged in the rural areas,” says Professor Prashanthi Narangoda.

She claims that although more Chinese people volunteer in the country, volunteers and voluntary organisations still lack focus on children in remote areas. “They’ve been all over the country. But my point is rather than focusing on the city schools, it is recommended to pay motivation to the rural areas in particular situations,” she says.

However, the outbreak of COVID-19 made it impossible for Chinese volunteers to continue to travel to Sri Lanka to conduct offline volunteer teaching activities. Volunteer organisations have had to find new ways of volunteering.

Virtual volunteer teaching projects are gaining popularity among Chinese voluntary organisations as a new form of transnational volunteering during the post-pandemic. The organisation runs online teaching activities by helping to build local networks and donating teaching equipment. The online volunteering project includes teaching activities and the construction of intelligent tutoring systems to support Sri Lankan schools.

The virtual volunteer teaching project has received much recognition since it started, as the relationship between the children and the volunteers is more purely that of student and teacher. The volunteers are asked to prepare the lesson beforehand as if they were teachers, rather than acting as playmates or teaching assistants for the children, according to Tiange, she was invited to join the virtual project.

“The volunteers have to prepare lessons based on a specific theme, and the children will sit in the classroom and listen to the lessons. They have to be prepared and understand what they will teach the children,” she says. “Online projects are not the same as traditional offline projects. Volunteers with a casual and perfunctory attitude can no longer go into an online teaching project.”

Rather than thinking of volunteering tourism as a way to experience a foreign culture, Tiange believes that the purpose of this online volunteering activity is purer. According to Tiange, this kind of virtual volunteering allows more people to use their strengths and really help people in need.

Tiange still remembers that on the last day of her volunteer tourism, the girl with an intellectual disability asked her if she would come back to see her again, which touched her very much. “The life of a physically challenged child like the girl was already more difficult than other children. Not to mention that she lives in a small village with less educational resources and poor medical conditions,” she says.

Having met many children with all sorts of difficulties in their lives, including the girl with an intellectual disability and some other children from low-income families, she now always emphasises with them.

Tiange hopes that Chinese volunteers and organisations will pay more attention to the needs of local recipient communities and make volunteer teaching truly valuable to the country’s education system. More children like the disabled girl can benefit from the volunteer projects Chinese volunteers offer.

“I think we should really consider what the children want, whether they want gifts or whether they want to learn something from the volunteers,” says Tiange.