The global pandemic is turning foreign students away, sending most UK’s universities into financial pitfalls. What would higher education look like in the next academic year?

They said there’s no point to go to the UK now because China is much safer.”

– CHristina Huang

Christina Huang rarely argues with her parents about anything so that when her father slaps on her left cheek in outrage, she is stunned. And in that split second, she knows something has broken: the relationship with her family, and her dream.

Growing up in China for 24 years, she always longs for an opportunity to study abroad. With lots of efforts, in January, when she finally received the offer from the University of Edinburgh, she was so delirious that she truly believed nothing could ever stop her from taking off.

Then the coronavirus landed, right in the middle of her way.

“My parents think it’s too dangerous to go because of the pandemic,” said Christina. “But I don’t want to give up. I insisted I will not change my mind. And they got really mad.” Without consensus, fights continued to take place on a daily basis.

“They said there’s no point to go to the UK now because China is much safer. Even postponing the course is not an option. They don’t think things will get better that soon,” she said. “But I just can’t let it go. I worked so hard to get the offer.”

And the argument started to get intense. Her parents threatened not to pay for her tuition fees and give her any money for living. She shouted back in anger and shortly after that, came her father’s hard smack.

Leaving the rash on her face in pain, Christina types out her story on Weibo, China’s equivalent of Facebook, surprised at the fact that many’s hopes of study abroad have also been dashed by the virus.

Among them, a few dropped out of the course voluntarily and the majority are still unable to make up their minds. “It’s not an easy decision,” said Jael Li, a Chinese student currently studying in the UK. “International students pay lots of pounds, nearly double the amount the locals do, but they are really not sure that what they pay for will deserve what they get.”

As remote teaching is expected to remain in place when the new semester began, many Chinese students found studying in the UK less attractive and in no way superior to staying in their home country. “We are losing the value of studying abroad,” Jael said.

Image source: Jael Li

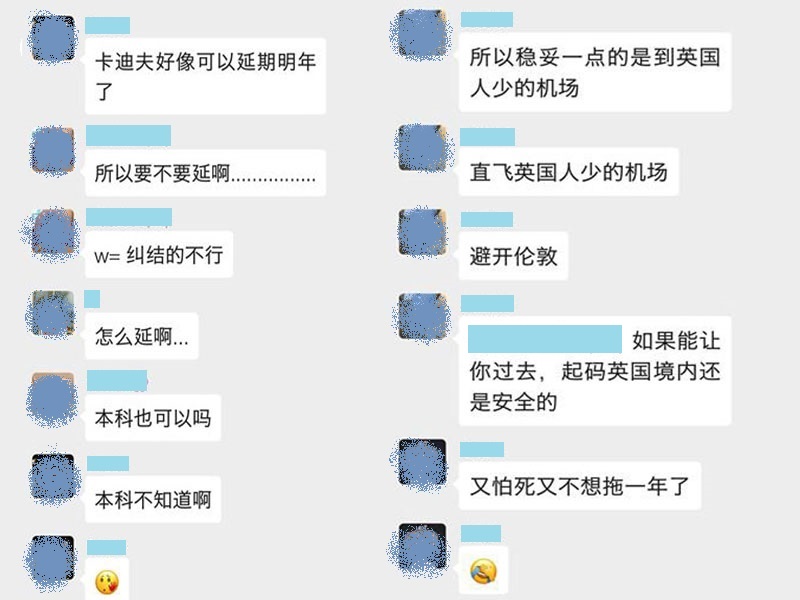

On WeChat, an online chatting application in China, the discussion about whether to postpone the study is heating up. Jael is in one of the freshers’ group chats, meant to give advice as a graduate, but anxiety has spread through conversations with many facing challenges and uncertainties in panic.

“Some students are worrying about their language. Because the IELTS test has been greatly influenced by Coronavirus and they have limited time to meet the requirement,“ said Jael, adding that most of them, who are supposed to study at Cardiff University this September, might be allowed to defer their study till next year with an additional amount of deposit.

Before the pandemic, the number of Chinese overseas students in the UK has surged by 34% over the past five years according to the Higher Education Statistics Agency.

However, in the 2020-21 academic year, the British Council published a survey revealing that around 24% of Chinese students had either already cancelled their plans or were highly likely to postpone the course due to COVID-19.

On top of that, universities also saw a significant drop in other nationals from EU and non-EU areas. London Economics warned this will blow a huge financial hole in higher education sectors with an approximate £2.5 billion of income decline, and over 60% of the figure was contributed by BAME students whose tuition fees are usually two or three times more than the locals’.

“Government must take urgent action to provide the support which can ensure universities are able to weather these very serious challenges,” said the Chief Executive of Universities UK, Alistair Jarvis, noting that this might put institutions having a high proportion of non-EU students “at risk of financial failure”.

On 4 May, the UK government responded to universities’ request with a package of measures including £2.6 billion worth of funding and business loan support, emphasising the top priority would be to ensure universities can continue to attract international students.

However, Universities UK said “further work will be needed” and many were still facing a shortage of research budget and cash flow.

Cardiff University, a member of Russell Group, expects to see a 20% plunge in university income next year. The Vice-Chancellor Colin Riordan said, “Even if the government funding were to be forthcoming, any benefit to Cardiff would at most halve that deficit, which would still leave us in an unsustainable position.”

Although it is the pandemic that leaves foreign students with no choice but to stay at home, causing a sudden loss of universities’ income, Professor Catherine Fletcher at Manchester Metropolitan University claimed that financial problems had already emerged since 2010 when research funding commenced to fall and overseas student enrolments became the main source of profits to fill the gap.

“There is some over-reliance on income from international students, although that varies by university and is worse in some other locations,” said a professor at Cardiff University specialising in social science and education, who requests to remain anonymous.

“What I believe some universities in the UK have not done well is to make investments beyond their core business of teaching and research,” he said, implying the risk to the education system includes the growing level of competition between universities.

Students are stuck in a system which threatens their education by leaving it to the whims of the market.”

– National Union of Students

Instead of improving the teaching quality, most universities seemed to allocate the bulk of budget to marketing.

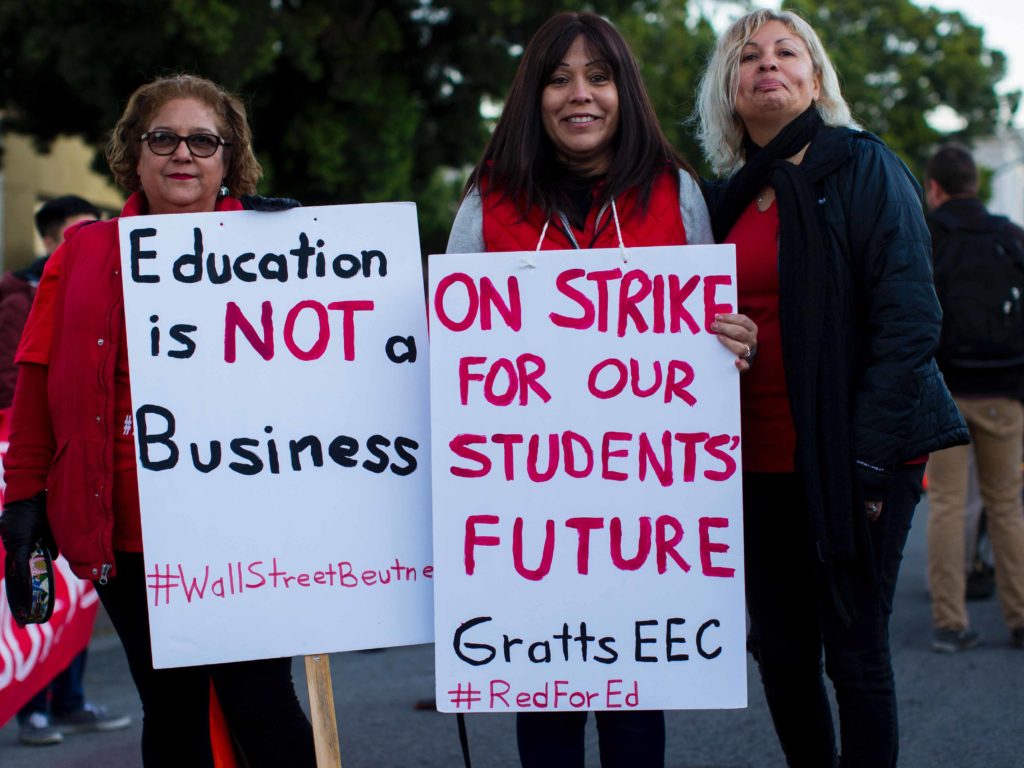

“The marketisation of higher education has failed students and created perverse incentives for institutions,” said Claire Sosienski Smith, Vice President of National Union of Students. “It would benefit students and society far more to promote collaboration among universities rather than wasteful competition.”

Claire then criticised the government for its measures against the financial crisis, saying: “The language used is very broad. Students are ultimately still stuck in a system which threatens their education by leaving it to the whims of the market.”

It is clear that what lies at the root of universities’ financial trouble is probably the commercialisation of Britain’s education system, whilst the pandemic seems to merely speed up the inevitable trend, making the weakness exposed.

Nevertheless, the urge to prioritise the quality of teaching can be far more difficult under the lockdown as most courses will continue to be delivered remotely. Professors across universities are attempting to brush up on their virtual techniques to provide students with a good learning environment.

As the relaxation of lockdown is underway, some universities are planning to re-open the school gradually over the coming months. “It may be possible to open the campus in a more limited way early in the summer to allow researchers access to labs and other facilities,” said Mr Riordan, of Cardiff University.

But, in an effort to observe social distancing, the campus will only be able to accommodate limited numbers of students and staff with strict hygiene measures. Those whose research cannot be done remotely would be prioritised.

This situation where access is restricted can take at least a year to 18 months or even longer. “There are still a great deal of unknown factors. Re-opening will be a gradual process and will require much detailed planning,” Mr Riordan said. “We will need to focus on student satisfaction and experience in these unprecedented circumstances.”

It is suggested that blended teaching might be an alternative way to give students more classroom-based learning but at the same time, universities should follow medical experts’ advice to cautiously allow classes to take place in small groups rather than large lectures.

Before virtual teaching began in March, Jael used to travel around Cardiff, learning about Welsh and British cultures, making new friends with people from different countries. Yet, none of these activities is available at the current stage.

The pandemic has deprived international students of the most valuable component of studying abroad: an eye-opening experience. While after having online classes at the end of last semester, Jael still thinks what she has learned throughout the year is worthy of the tuition fees.

“Before I came here, I was like a frog in the well,” she said, “I feel my world has suddenly opened. I’ve got to know a society that is totally different from China. I would say if newcomers have thought the underlying risks and know what they want, the UK is still a really good option to study.”

More story about foreign students in the UK

How is a Spanish student fighting against COVID-19 by doing voluntary work?