Behind rising rents and long work hours, students are struggling to survive at university. Will higher education still be worth it for them?

On a summer evening, while many of his friends are out relaxing, 18-year-old Danyal Ahmed is sitting alone, worrying about money. He’s at his former college, finishing a part-time shift that pays just enough to cover the occasional outing.

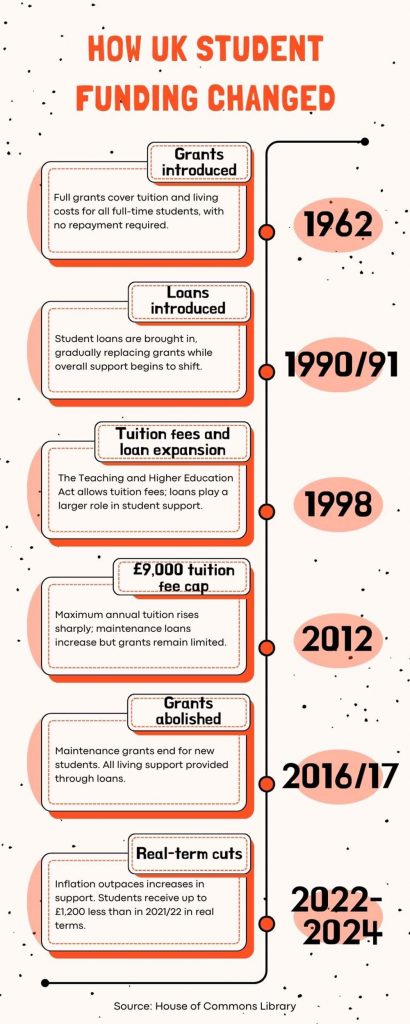

Danyal hopes to begin studying business management at the University of Birmingham this year. His tuition fees will be covered by a student loan. However, the maintenance loan he qualifies for is less than £5000 per year, not even enough to cover the £6000 rent for his accommodation.

If the loan can’t even cover rent, Danyal says he will have to borrow a large amount from his parents. But that won’t be easy. “My mum is disabled, she’s legally blind, so she gets disability allowance. And my little sister’s disabled too, she has autism. Our outgoings are a lot higher. We spend more on childcare and taxis because my mum can’t drive. The cost of everything is already really high, so for them to support me at university as well is going to be a lot,” says Danyal.

Although the part-time job gives him some income, it’s far from enough to make a real difference. “I work after college hours. They have teams come in and use the football pitch and the sports hall, and I stay here for four or five hours and then lock up after everyone’s left. I get £12.45 an hour, which is above minimum wage, but I only work eight hours a week,” says Danyal.

With only two shifts per week shared among three workers, his earnings come to about £400 a month. Even so, this money isn’t just for savings, he explains, “I still want to enjoy myself and spend time with my friends before university.” He recently spent £300 replacing a broken guitar, a decision he made reluctantly. Now, he has stopped buying clothes altogether, trying to put aside every possible pound.

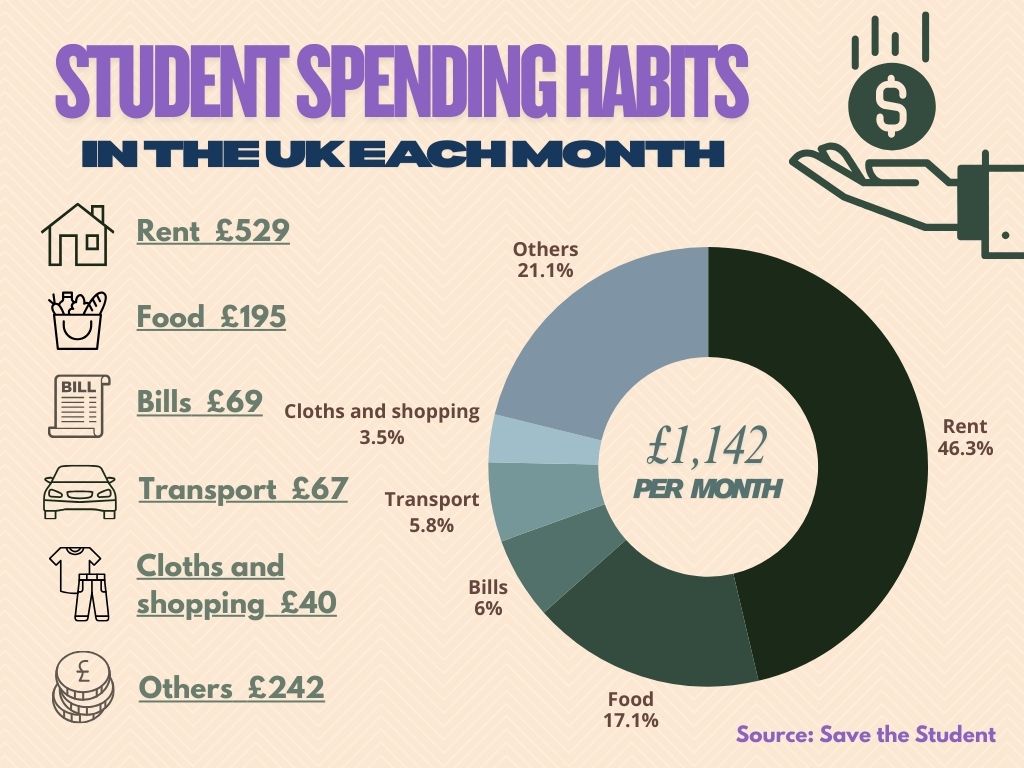

On top of that, rent sits at the centre of his calculation. It is the single biggest cost and the place where the numbers first stop adding up. At Birmingham, where Danyal will start in September, basic student accommodation costs £146 a week for a room with no ensuite, no sink, just a bed, a wardrobe and a desk.

“The cheapest one is £102 a week, but that is a really rundown place. It’s shared bathroom, shared kitchen. The stories I’ve heard from people living there, they have like mould on the floors and it’s really grim and dirty,” Danyal says. “The next cheapest option jumps up quite a lot. If you want an ensuite at Birmingham, the cheapest you’re looking at is £192 a week.”

Across campuses, leaders in student groups say the pressure from housing is building rather than easing. At Cardiff, Micaela Panes, who served as Vice President for Postgraduate students at Cardiff University Students’ Union until June 2025, says the Students’ Union opposed a 6% rise in university accommodation costs this year, but the increase went ahead despite protests. When rent absorbs most of a student’s budget before term even begins, everything else becomes a choice between cutting back or doing without.

The national picture points the same way. The financial squeeze is fundamentally changing what it means to be a student. Notably, 42% of UK university students now survive on less than £100 per month after paying rent and bills, according to the National Union of Students.

Nearly all are cutting back on basics, with more than half spending less on food. Some have stopped buying sanitary products. Three quarters socialise less to save money. Behind each number is a small decision made again and again: skip a meal, miss a night out, say no to a club or a trip because there is no space left in the budget.

Once rent and bills have taken their share, there are few ways to close the gap. For many, part-time work becomes the only option. For Danyal, that means locking up the sports hall after hours, counting every shift and every hour. He knows that will not stretch far.

It’s the little sort of five, ten, or twenty pounds you spend, but then they add up so much and you’re like, where’s it gone?

– Yasmin

The worry is not only about paying for necessities, but about what kind of life will be left around the edges of study. “There was somebody who said they worked and studied and basically had no social life. All they did was work and study,” he says. “To be honest, that’s what it’s gonna be looking like for me unless I can get additional funding from the university. If I can’t get a grant or loan from the university, then it’ll probably just be working nights and then doing my studies in the day. That’ll probably just be my life.”

Some students reach university with savings from years of work. That can soften the first weeks, but it does not remove the gap between loans and real costs over a full year. This is the position of Yasmin Goma, 21. After leaving college she tried the apprenticeship route, but found it offered little chance to move up.

She has worked almost full time for three years and managed to save some money, but now, as she prepares to study Global Sustainable Development at Sheffield, she still fears it will not stretch far enough. “I think it’s the day-to-day spending, like it’s gonna be the sort of going to Tesco’s and checking there’s nothing in your bank account, but you still need to eat for the rest of the week. It’s the little sort of five, ten, or twenty pounds you spend, but then they add up so much and you’re like, oh my gosh, where’s it gone?”

Like Danyal, she expects to juggle work and study just to get by. “I’m really privileged to live with my dad right now and he covers rent and bills and stuff, so luckily I’m able to put a decent portion into my savings at the moment. But I know I won’t be able to keep that up at all in the university. I definitely plan to get a part-time job, but it’s probably gonna be less spontaneous and probably more budgeting once I start.”

Finding work is just the first step. Making it fit around lectures is another. When her university told her that students should be studying 40 hours a week including lectures, Yasmin realised the scale of the task. “It’s gonna be difficult for sure. I think it’s just about making a plan and not overworking yourself. I think making it clear to employers that you are available certain times, like you might be available these two days a week and that’s it. Not letting employers call you up at 9 PM the night before asking you to do a 12-hour shift,” she says.

Student leader says this is no longer a handful of hard cases, but a daily reality on campus. “More students now work alongside full-time study than ever before, which can impact their ability to attend lectures and seminars, complete assignments, and even find time to rest or socialise,” says Micaela.

The numbers confirm what she sees daily. According to National Union of Students data, 69% of students now work part-time on top of their studies. Of those working, nearly 1 in 5 work more than 20 hours per week alongside full-time education.

The cost is clear: 34% say work has a somewhat negative impact on their studies, with another 4% reporting a very negative impact. They report tiredness, struggling to juggle commitments, and having less time for studying. These aren’t just statistics but daily compromises: missed lectures for shifts, assignments rushed between work breaks, exhaustion that makes concentration impossible.

When exhaustion becomes the norm, mental health inevitably suffers. Cardiff’s counselling waiting lists have reached record lengths, and students report rising stress and anxiety. “There is support in place through the University, but it is not enough,” Micaela says. “And I believe financial pressures have a role within this.”

With such limited help available and mounting financial pressure, it’s no surprise that many students are losing faith in the value of higher education itself. Rachel Leighton, Head of Cardiff University’s widening participation team, says the cost of living has changed how young people think about the future.

Some worry that even if they do get a degree, inflation will eat away at the salaries waiting for them afterwards. “A young person could look at rising prices and loan arrangements that have remained largely static and start to wonder whether university is actually achievable or worth it,” Rachel says.

Behind these doubts lies another truth: reaching university at all is already an achievement for many. Unlike their peers from affluent families, some grow up moving between temporary homes or even hotels, others share a room with several siblings and struggle to find quiet space to study. For many, free school meals may be the most reliable part of their diet.

“Educational disadvantage starts really young,” says Rachel. “It begins with whether your parents have the time and capacity to sit down and read with you. It also depends on whether they can send you to nursery, where you get additional opportunities and socialisation. These gaps become embedded very early, and children can end up falling behind their more advantaged peers.”

That early gap helps explain why the cost of living crisis bites so hard once these students arrive. The pressure is financial, but it is also about confidence and participation. “While universities are far more diverse than they were, students from low-income backgrounds still often report feeling out of place socially,” says Micaela.

Universities are trying to respond, but their efforts reveal the gap between intention and impact. At Cardiff, Rachel points to various support systems: bursaries for low-income students, hardship funds for acute need, and targeted programmes like “Together at Cardiff” for vulnerable groups including young parents, care-experienced students, and asylum seekers. The university tracks outcomes through internal dashboards, comparing students from different backgrounds to identify where support is needed.

– Rachel

A young person could look at rising prices and loan arrangements that have remained largely static and start to wonder whether university is actually achievable or worth it.

Yet these measures struggle to meet the scale of the crisis. “It can take weeks for an in-person counselling or wellbeing appointment, and students with ongoing financial difficulties are often told to just ‘get a job’ when they may already be working one, and to access the hardship fund students must go through vigorous and demeaning financial history checks,” says Micaela.

Students and their unions have stepped in where formal support falls short. The Cardiff Students’ Union runs a “Feed your Flat” campaign to help with basic needs. “Every few weeks we set up stalls in both the Cathays and Heath campuses which allow any student to pick up cupboard essentials, cost and judgement free,” Micaela explains. “We are looking to expand this by piloting a ‘Pantry’ in the Students’ Union for students in need to pick up essential items whenever they need them.”

While these initiatives help, they cannot fix the bigger problem. Rachel acknowledges that universities face their own financial pressures, with rising staff costs and limited government funding. “It’s hard to see how further investment in educational outcomes is necessarily on the cards at this time,” she says. “Which is a shame because it ends up being a false economy. If we don’t support young people to do well at school, their outcomes as adults are worse, and they’re less productive.”

For students navigating this broken system, the unfairness cuts deep. Danyal sees others getting more support through dishonesty while his family’s genuine needs go unrecognised. “There are so many people I know that are not being honest and basically lying about how much their family earns and then getting more money because of it, which isn’t fair on people who needed it,” he says. “They don’t take into consideration the cost of living crisis. It costs so much more to support a family than it did ten years ago, and it is really expensive just to survive,” says Danyal.

The weight of these pressures isn’t new to Danyal’s family. When asked about being the first to attend university, he pauses. “My dad went to uni, but he dropped out. He had to drop out to get a job and support his family.” Now, a generation later, the same choice waits.