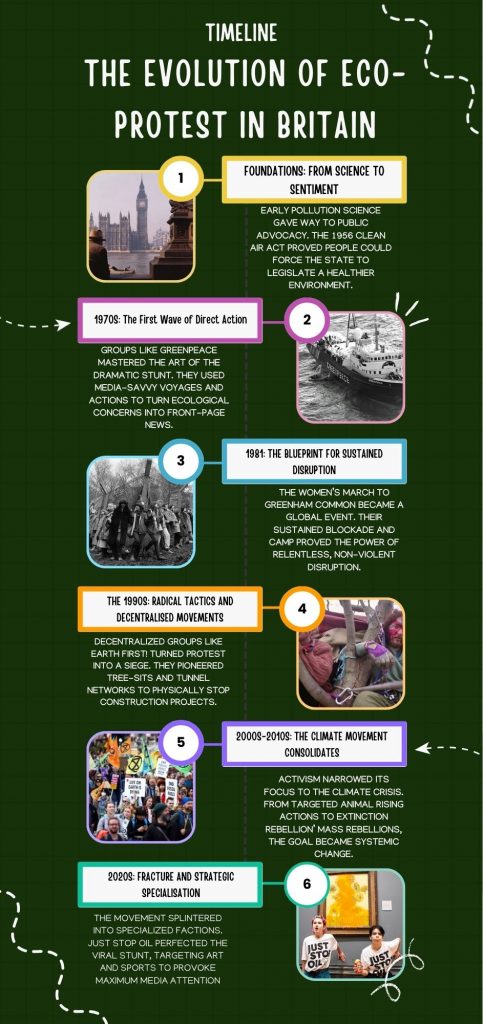

Once confined to marching and petitions, protest in Britain is becoming riskier, more disruptive, and increasingly illegal. For some, climate activism now means courtrooms and time behind bars. What drives them to take that risk, and what is the price of taking action?

It was 1981, and the September air shimmered not just with the first sharp bite of autumn, but with a fierce maternal determination. A small group of Welsh women set out from Cardiff, bound for Berkshire’s Greenham Common Royal Airforce Base. Their 100-mile march a pilgrimage against the stationing of American cruise missiles on British soil – weapons of mass destruction, foreboding total nuclear annihilation.

As they trudged down narrow country lanes, something extraordinary happened. People began joining, not hardened radical activists, but ordinary women: mother’s fearing for their children’s futures, shop workers, schoolteachers, librarians, nurses. By the time they reached the barbed wire fences of the Common, their numbers had swelled and what began as a protest march birthed a years-long peace camp, a vibrant, defiant, all-female community, living in the shadow of nuclear militarism.

The Greenham women didn’t seek applause. They occupied base entrances in broad daylight, padlocked to fences in the cover of darkness, and chained themselves immovably to gates, forming human barricades against the machinery of war. Their motive wasn’t mass-appeal or fleeting headlines; it was a desperate, visceral need to be heard, to force a willingly deaf government to listen to their screams of reason. They were not career activists, but citizens frustrated by political inaction, pushed beyond the boundary of lawful dissent by a threat they deemed morally unconscionable. Their crime? The belief that preventing global incineration justified trespass and obstruction.

Forty years on, different existential threats loom, casting a longer shadow. “At what point do we escalate? When do we conclude that the time has come to try something different?” Asks Andreas Malm, a Swedish climate theorist whose work has become a rallying cry for a movement grappling with the inadequacy of peaceful protest against planetary destruction.

The climate emergency and potential for human extinction has ushered protestors into a stark new era. The slow marches and mass mobilisations that defined early environmental movements now feel ineffective to many activists. In their place, a new wave of coordinated, disruptive, and often illegal direct action, has surged. Motorways grind to a halt as activists glue themselves to the tarmac. Airports, oil terminals, pipelines, all face occupation, their critical flows interrupted. High-profile sporting events become stages for urgent intervention. The facades of revered institutions – banks, insurers, energy giants – bear the imagery of symbolic vandalism. The message is one of immediacy: business as usual will kill us. And as scientists continue to warn of earth’s coming fate, activists tactics grow ever more confrontational.

Movements like Extinction Rebellion (XR) and Just Stop Oil (JSO) have thrust civil disobedience back into the spotlight of mainstream debate, often polarising opinion. But beyond the sensationalised headlines, viral videos, and drawn-out legal battles in magistrates’ courts, stand individuals startlingly ordinary. They are people who once had proper educations, steady careers, loving families, and clean criminal records. Now, they grapple with a profound question: how far is too far, and what price is worth paying?

“Silence, I think, is far more dangerous than speaking out,” reflects Jane Rendel, her voice weighed by decades of frontline activism. Her journey began long ago, forged amidst the fences of Greenham Common, and 1980s anti-nuclear marches. A testament to the enduring spirit of resistance against overwhelming threats.

Jane Rendel

(Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Greenpeace, Amnesty International, Friends of Palestine)

Now in her seventies, Jane Rendel is a protest veteran whose activism stretches back to the anti-nuclear campaigns of the early 1980s, including the iconic Greenham Women’s Peace Camp. Arrested several times in her decades of involvement with CND, Greenpeace, and other social causes, she shackled herself to fences and faced down authorities in the belief that preventing nuclear war demanded serious action. Whilst retired from the high-risk stunts of her past, her commitment to facing injustice remains undimmed. Today, she actively campaigns for the release of political prisoners through Amnesty International, and for the end of genocide through Friends of Palestine, channelling a lifetime’s experience into advocating for human rights and facing up to the powerful, an embodiment of the long arc of moral resistance.

“What drives me?” Rendel asks, settling into a chair in her Somerset garden. “well, I suppose I’ve always felt compelled to act if something truly matters. Some people find their motivation in faith, others in family, perfectly valid of course, but for me it’s always been about principle. If I see something unjust or dangerous, I can’t simply stand by.” her gaze, steady and clear, reflects decades of confronting uncomfortable truths. “I was part of CND at a time when protesting carried genuine risk. But the danger never outweighed the moral imperative. I do think, if one believes in something deeply, one must act accordingly, even if it’s uncomfortable. Especially if it is. There’s no nobility in staying quiet just because it’s easier. You have to be able to look yourself in the mirror and say, ‘I saw what was happening, and I did what I could.’ not everything, we’re only human, but what I could.

Rendel’s perspective bridges decades. The missiles at Greenham Common represented an immediate threat of annihilation. Today’s climate crisis, whilst unfolding in slow motion for some, carries the same threat as nuclear war for an increasing portion of the globe. The perceived failure of conventional political channels – voting, petitions, lobbying – has pushed a new generation towards the disruptive tactics Rendel once employed, but amplified for a media-obsessed age, and against a threat deemed even more pervasive.

Phoebe Plummer

(Just Stop Oil, Extinction Rebellion)

Phoebe Plummer, a prominent Just Stop Oil activist, became a globally infamous figure after throwing tomato soup over Van Gogh’s Sunflowers at the National Gallery in October 2022. A former Extinction Rebellion member, she represents a generation embracing high-profile, controversial stunts designed to shock the public into climate awareness. Her action, demanding an end to new oil and gas licenses, resulted in a two-year prison sentence.

Plummer exemplifies the shift from traditional protest methods, towards calculated, media-driven disruption, willingly sacrificing her liberty to force a conversation deemed impossible through polite channels.

For Phoebe Plummer, the catalyst for action wasn’t abstract policy failure, but the visceral reality of human suffering on an unconscionable scale. “There was a study in Nature,” she states, her intensity palpable, “it found that by 2030, there’ll be 2 billion people displaced simply because it’s too hot to live where they are. Two billion—it’s a number so huge we can’t comprehend it.” she pauses, letting the immensity sink in. “But those are 2 billion real people. With names and faces and lives just as important as mine and yours. What if you met those people, really looked them in the eyes, and saw their humanity?”

“What do you want to be able to say to that person that you did? Do you want to say you kind of tried to forget about it because it’s so overwhelming and so scary? Or do you want to be able to say… yeah, I did everything I could, I did everything I thought was humanly possible for me to do?” for Plummer, the soup on the glass protected Van Gogh wasn’t vandalism, but a desperate, symbolic alarm bell. “That’s why I do it… so I can live with myself in years to come, so I know that I can say to a displaced person, or to someone even younger than me that I did everything I possibly could.” her two-year sentence is the stark price of that conviction.

Anna Holland

(Just Stop Oil, Extinction Rebellion)

Anna Holland, alongside Phoebe Plummer, made headlines during the 2022 Van Gogh soup protest. A committed Just Stop Oil and former Extinction Rebellion activist, Holland’s actions were driven by a deep-seated belief that conventional protest forms had failed. Her 20-month prison sentence underscores the personal cost of committing such a media-grabbing act of civil disobedience. Holland embodies the discourse that when faced with governmental inaction on existential threats, disruptive tactics, regardless of their contentious nature, become a necessary moral imperative to force once-under discussed issues into the public and political agenda.

Anna Holland reiterates this sentiment, focusing less on abstract future victims of the climate emergency, and more on the immediate, collective need for resistance. “What matters…” she states, her tone urgent “is that action is being taken. What matters is that line is being crossed, and that people are standing up. It doesn’t matter who those people are, it’s the fact that they’re doing something. That’s the important thing. That’s the thing that gets lost in this all the time.” For Holland, the identity of a protestor, whether they’re a seasoned veteran activist, or an inexperienced first timer, is secondary to the act of resistance itself. Holland envisions a mass-resistance movement of overwhelming pressure.

“We need to see the government, the system being attacked from all fronts. You know, wherever they look, there’s someone in the road, there’s someone chained to everything… there needs to be direct action. Now, more and more, people are stepping up into direct action, which is what we need to see.” Her 20-month prison sentence stands as a symbol to her belief that crossing the line is not only justified, but essential to our state.

James Skeet

(Just Stop Oil, Extinction Rebellion, Animal Rising)

James Skeet is an early and ongoing activist with Just Stop Oil who was deeply involved in their foundational wave of protest actions, having been brought into the group due to his expertise in organising direct protests for Animal Rising. He has participated in numerous high-risk protest operations, including the multi-day occupation of oil terminals, strategic sit-ins on key transport arteries, and scaling gantries above motorways. Arrested multiple times, Skeet’s activism reflects a pragmatic, yet somewhat reluctant embrace of direct-action tactics, born from a profound disillusion with the traditional political process and a deep conviction that only sustained, direct economic disruption to the state, will force the government to take action on fossil fuels.

Skeet embodies the weary end of the activist spectrum. He admits openly that he finds no enjoyment in confrontational protest “I don’t particularly like the method. It’s really unpleasant for me, but the fact of the matter is we wouldn’t be doing it if it didn’t work…” his frustration with the status quo is clear “History’s shown time and time again… It’s a really uncomfortable thing for people to be engaged with [direct action] because whenever you ask them ‘what would you suggest?’ they never have a fucking answer. Their answer is ‘oh, well, you should vote because we live in such a functional democracy.’ well, we fundamentally don’t… Or they’re like ‘write to politicians.’ well politicians don’t serve the interests of ordinary people. They serve corporate interests overwhelmingly.” For Skeet, occupations and sit-in protests are not stunts, but necessary acts of state sabotage against a system he sees as inherently corrupt and unresponsive to the climate crisis. The arrests he’s suffered are simply an occupational hazard, a necessary sacrifice in a war he feels has already been declared on the future by those who hold power.

This consuming disillusionment with the democratic process is a common thread, pushing activists beyond traditional methods of engagement. Activists point to continued subsidies for fossil fuels, and climate targets constantly missed despite government promises. This perceived betrayal of the people by the officials who elected them only fuels the belief that direct, economically disruptive protest, is the only way to break the climate inertia.

Julian Wiltshire

(Revolutionary Communist Party, Extinction Rebellion)

Julian Wiltshire was a disgruntled student during Extinction Rebellion’s initial surge, heavily involved in their early protest waves of mass civil disobedience that brought central London to a standstill. Since departing Extinction Rebellion, his activism has taken a more explicitly political-economic turn. Wiltshire now campaigns under the red banners of the Revolutionary Communist Party, focusing on systemic critique and driving radical political transformation. His journey from environmentally focused civil disobedience to revolutionary politics highlights the trajectory of some activists who conclude that solving the climate emergency is inextricably linked to replacing the unsustainable and exploitative capitalist system in which Britain resides.

Wiltshire’s path reflects another dimension of this evolution. During Extinction Rebellion’s first wave, he witnessed the power of mass disruption. Yet, his focus has now shifted. “The climate crisis isn’t a standalone issue,” he argues. “it’s simply a symptom of a system built on endless extraction, exploitation, and inequality. Extinction Rebellion were moving in the right direction, absolutely. But they didn’t get to the real cause – capitalism. Protest isn’t enough if the system we live in is destroying the planet and immiserating the masses.” Wiltshire’s move to campaign with the Revolutionary Communist Party signifies a belief that solving the climate crisis required not just policy change – but fundamental systemic transformation – a revolution against the very systems activists like Plummer and Rendel and trying to disrupt. “You can glue yourself to an oil terminal, but if the economic system that demands oil keeps functioning, what then?”

Wiltshire’s shift underscores a fracture in the broader protest landscape. While groups like JSO focus on stopping new fossil fuel projects through direct action, others increasingly frame the struggle as one against the system itself. This ideological divergence highlights the breadth and depth of the crisis, and the movement against it.

Beyond prison sentences, activists face job loss, family rifts, social ostracization, and the unending strain of legal battles. The psychological toll of living in a state of perpetual crisis and confrontation is heavy. Activists are often vilified in the media, by politicians, and the public. They are called extremists, vandals, eco-zealots, and loons, their motives for protest questioned and their condemned.

What Comes Next?

Yet, they persist. Like the Greenham women who left warm homes for the cold surrounds of a base and the stark interiors of police cells, today’s activists share their moral compulsions. They’re not blind to the disruption they cause or the anger they provoke. But weighed against the unfolding catastrophe – droughts, floods, heatwaves, extinctions, and the displacement of billions, the greater crime is inaction.

The legacy of Greenham Common goes on, posing a persistent question: at what point does conscience compel law-breaking? History ultimately judged the women of Greenham Common differently: the missiles were removed, the Cold War ended peacefully. Today’s climate activists operate on a similar hope – that future generations will assess their actions not primarily through the lens of disruption (splattered paint, halted traffic), but through the context of escalating scientific warnings and institutional responses deemed insufficient by the activists themselves. Their gamble is that the focus will fall on why they acted with such urgency.

Ordinary people are increasingly crossing the line into civil disobedience. Their driving force is not chaos, but an innate conviction: that systemic responses are failing, time is critically short, and the viability of a stable future stands in the balance. Whether viewed as heroes, villains, or something more complex, their willingness to accept significant personal consequences, including arrest, imprisonment, societal censure, stands as a stark indicator of how deeply they perceive the crisis, and how desperately they seek to alter its course.