As Wales aims for one million speakers in 2050, what are the motivations and benefits of adult Welsh learners across Wales?

Jerseys of green and gold, black and white, green, blue and crimson descended on New Zealand as rugby fans from across the globe congregated on the small island nation to support their teams in their bid for Rugby World Cup. With them, an array of languages danced through the streets, languages of love, of Germanic descent, and even from distant Celtic lands.

For Kierion Lloyd, a proud Welshman from Wrexham this was a watershed moment. He was far from home – some 11,000 miles in fact – and suddenly he was looking at himself and his national identity differently. He couldn’t speak Welsh and for him, that was not okay.

“I guess there was maybe an element of shame in myself,” he says. “These people who’ve heard of Wales or maybe never heard of Wales, wanted to hear me speak in my native tongue – and I couldn’t.”

Being in New Zealand, with its inevitable comparisons to Wales – a love of rugby, being the smaller sibling of a larger country with its own endangered native language – acted as an extra motivator. “They are fighting to protect their language. And there was almost a comparison,” he says. “Welsh is probably one of the oldest European languages going, certainly the oldest language in the United Kingdom. So why should I help kill it off by not speaking it?”

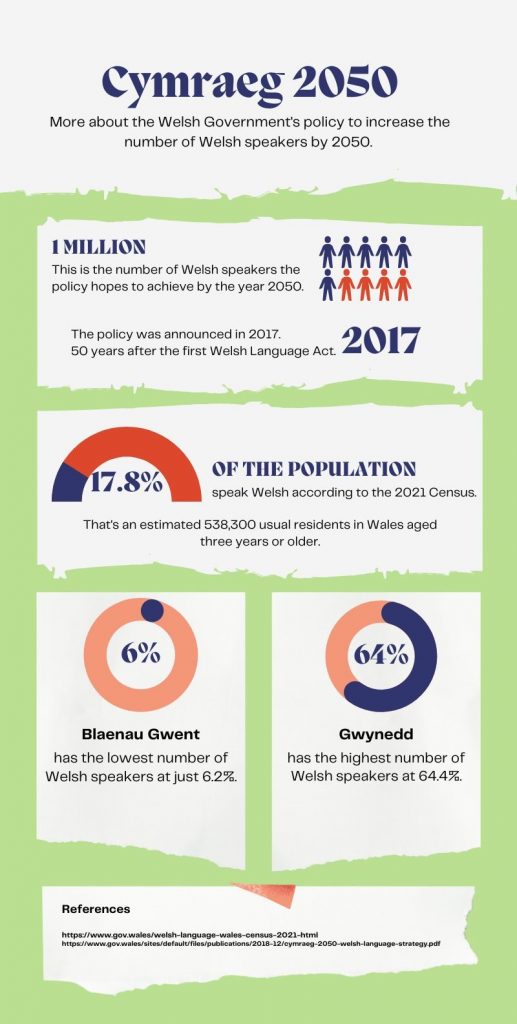

Keirion is not alone in his desire to keep Welsh alive. The Welsh Government want to ensure that Welsh is here to stay – so much so they’ve made it a policy, Cymraeg 2050, to ensure that there are one million Welsh speakers by the same year.

So, then, what do adult learners like Keirion have to offer for the preservation and rejuvenation of Cymraeg?

The Welsh coastline runs for 1,680 miles, taking in seaside towns like Tenby in the west and Colwyn Bay in the north before reaching the England-Wales border to the east. This line separates the two home nations for around 160 miles from north to south following roughly the same route as the 1,000 year old Offa’s Dyke.

At the southern end of the border lies the Severn Estuary and two towns – Sedbury and Chepstow. Though they are separated by just 100 metres of water, in reality, so much more divides them. One lies in England and the other, in Wales.

The market town of Chepstow, Wales, is where Millie Hitchcock grew up – a place where a person’s national identity was always up for debate. “People that are my age are much more likely to be either really strongly Welsh or really strongly English,” says Millie. “It’s sort of like you don’t want to be in between and kind of need to pick a side, because it’s such a mixture of people.”

Despite growing up in an English-speaking household and by her own admission sounding “English” Mille says: “I’m Welsh, not English.” This assertion may be rare, considering Chepstow is part of Monmouthshire, an area which would fit into academic John Balsom as “British Wales” – where people identify more with Britishness.

According to Balsom’s 1985 model, Wales can be broken up into three “fuzzy” categories, Welsh Wales, British Wales and Y Fro Cymraeg. In Welsh Wales, people don’t speak the language but feel Welsh in places like Rhondda, Merthyr Tydfil and Caerphilly. In Y Fro Cymraeg, people speak Welsh and identify as Welsh in places such as Caernarfon and Conway whereas British Wales includes Brecon, Wrexham and Monmouthshire.

Balsom also asserted that those who speak Welsh feel more Welsh, which is a view that Millie has experienced first-hand. She recalls a time when an orchestra teacher asked her where she was from, “Wales,” she replied. “Do you speak Welsh?” the teacher asked. Millie said no, only for the teacher to quip: “You’re not Welsh, then.”

This is something that the Welsh Government would seek to address with Cymraeg 2050 – given the assertion that “Welsh belongs to us all”. The larger vision of the initiative can be broken down into three categories, increasing the number of speakers, increasing the use of Welsh and creating favourable conditions for the language to grow with infrastructure and community support.

On this target, Martin Johnes, professor of history at Swansea University says: “Having a target makes some kind of sense, but a million is just a random number. To me, it’s the wrong thing,” he says, adding that having speakers is one thing but using it is when a language really lives.

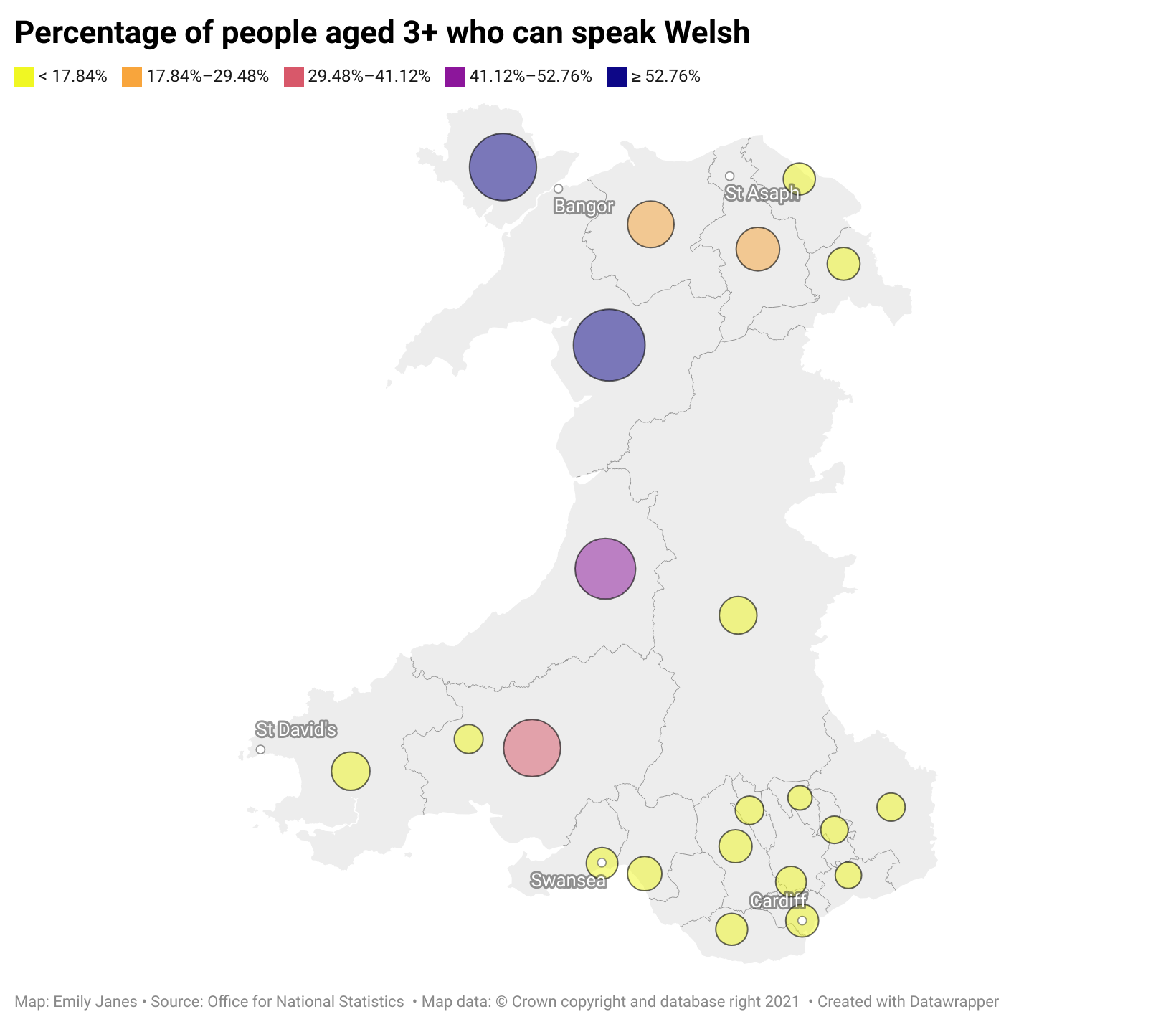

The numbers too have been disappointing recently. According to the Census 2021 by the Office for National Statistics, all local authorities except four saw a decline in people over the age of three speaking Welsh.

Millie’s Welsh journey started by attending an English-medium primary school where it was “taught by teachers who didn’t even speak Welsh” and views that the language was “dead”. She returned to it in a rather roundabout way in her early 20s, by studying French and Italian and then, linguistics and French minority languages. The latter made Millie think about another minority language – Welsh.

After starting with a tutor and then working with LearnWelsh – which, according to learnwelsh.cymru had 14,965 unique learners in the 2020/2021 academic year – she now has new opportunities. Those are academic, as her dissertation focuses on the language in Gwent and Glamorgan. “I’ve been able to reach out to so many different people and actually, like be able to communicate in Welsh,” she says, “that’s been really good.”

There’s also a chance to speak to some of her Welsh-speaking family too but there’s also something deeper. “Being able to speak Welsh would legitimise me a lot more in saying, I’m Welsh,” she says, “it kind of adds this sort of, like a layer of authenticity to my Welshness by being able to speak Welsh.”

The same is true for Kierion, who says the language is also about “reclaiming” his Welsh identity. “I don’t feel that this is something I judge others by. But I felt for me that I felt a little bit less Welsh by not speaking Welsh,” he says.

Kierion started to learn Welsh in school but spent a some of his childhood in Essex – where Welsh, unsurprisingly, wasn’t on the syllabus. Returning to live in Wrexham after his time in New Zealand allowed him access into a “club” that he didn’t have membership in before.

“I felt there’s almost there was maybe a little club that I was on the outside of by not being able to speak it,” he says. But now he’s got several memberships. “ It’s opened me up to these new experiences,” he adds.

He’s attended the Eisteddfod as a learner, he says: “It was getting a chance to practice my Welsh in the wild.” Welsh music is also something that has been a massive plus for him. “One of the main ‘doors’ that has opened is music – I was a music lover before learning Cymraeg, but have been exposed to bands and artists that I would have been oblivious to if I wasn’t learning the language,” he says. This has led to lots of performances and helped build his confidence after more and more chances to practise Welsh in the “real world”.

Like Kierion, Helen Murray is a Welsh learner who lives in Wrexham. after moving back home after working in Manchester for a number of years as a freelance journalist. Helen’s decision to learn Welsh includes a bigger challenge – completing a podcast interview completely in Welsh.

This is something she completed in November 2022. In fact, Helen’s Welsh has come on leaps and bounds and is now entering the ‘Advanced’ level after just two years of learning. This is despite Helen’s experience learning Welsh as a second language in school, where the atmosphere wasn’t exactly encouraging. “People just didn’t really care,” she says, “I don’t think anyone really loved it. I don’t think it was hammered into us that, actually, it could be quite a useful sort of skill to have.”

She does, however, think that times have changed. “That was just the attitude at the time. Whereas now, clearly, there’s a such a huge push to actually speak it.” One push is the Cymraeg 2050 policy which involves shorter strategies to reach the target. Education is a large part of the focus with the most recent strategy suggesting that a Welsh-medium Education Bill could be tabled.

But historian Martin Johnes notes that education is not going to be the key to increasing the number of Welsh language speakers. He says: “Education didn’t take it away and won’t bring it back.”

“Choosing to raise your kids in Welsh and sending your kids to Welsh schools. You know, those things are really important. But education alone is not going to save the Welsh language.

“For me, what’s important for the future of the language is that it’s a community language that people speak in the street, speak with their friends, speak in the pub. that’s never going to happen in the valleys or Cardiff or Swansea. The future of the Welsh language as a community language depends what happens in the north, on the west,” he says. This is where the “emphasis” of the policy should be in order to keep the language “ vibrant.”

In recent years there has been a great deal of media attention on how Welsh-speaking communities have been threatened due to people buying second homes in the areas, pushing up prices so that locals can’t afford to live in the area. The Guardian previously reported that Welsh language group Cymdeithas yr Iaith, has argued “destroying” Welsh-speaking areas.

I think it is respectful to try.”

Cathy Jackson

One of the areas affected by an influx of second home owners is Anglesey, the small northern island where Welsh learner Cathy Jackson lives. Cathy, who was born in Wales but brought up in Cheshire, came to Anglesey when Brexit took France off the table as a possible retirement destination for her and her husband. Wales, with its own language and unique culture, proved a valid second choice.

But in truth, Cathy, who has Welsh ancestors, had always felt a pull to Wales. Now, she says: “I don’t know why, this is the first place that actually felt at home.” And to make it feel even more like home among the other residents of Anglesey – where 55.8% of the island’s population speak Welsh as part of the ONS 2021 census – Cathy started to learn Welsh.

“I want to be part of where I am,” says Cathy, “I think it is respectful to try and even just …please and thank you if nothing else.” But her language learning journey has taken her much further than “plis” and “diolch” – even if she first “mangled” the language when she tried to speak it. “I think people too many people think you can just go to your two and a half hour lesson once a week and you’ll be able to speak. And it’s just not like that, is it?”

And so Cathy practised with neighbours on both sides, the receptionist at the GP surgery office who told her that they would help her “anytime” and with good friends from her village even though they had to speak English to her “a lot”.

Three years later, there was a moment with those same friends one summer evening over a glass of prosecco, Cathy says: “I hadn’t really realised that they had been speaking Welsh the whole time. Just understanding it, to chip in…it was such an amazing moment.”

Now, Welsh adds to her “lovely, friendly way of life” but also speaks to something deeper. “It’s the very first thing I’ve done for myself,” she says, “[I’m] absolutely fascinated with languages and what they tell you about…the people and the culture.” For Welsh – this is an innate kindness, reflected in the language and the people. “Welsh doesn’t have any really horrible swear words,” she says, “It’s just nice and gentle.”

It’s also about her family history “I suppose it’s like a missing piece,” says Cathy, “this is something that I feel was taken away from our family generations ago. And I feel like I feel like it’s my duty to get back.”

Rather than moving into Wales to learn the language, some, like Steven Griffin, learned once they left the country. Originally from Merthyr Tydfil, Steven has lived in Scotland and worked as a music teacher for decades. He didn’t come across any Welsh speakers until he went on a summer course with a national choir and met attendees from all over Wales – Cardiff, Aberystwyth, north Wales.

There, he felt “looked down upon”, he says: “I really felt a lot of polarisation there because the Welsh-speaking clique very much looked down on us Saes (English speakers) because we didn’t siarad Cymraeg (speak Welsh).”

Rather than inspiring him to learn the language, it put him off for quite some time. That’s not to say his home life was without Welshness. “We didn’t class ourselves as anything other than Welsh,” he says. Red shirts, leeks on St David’s Day and rugby were a big part of the culture. “Watching Gareth Edwards, JPR. And all that bunch,” he says, there was “pride in Welsh identity via rugby”.

Now, he’s a Welsh learner. He was prompted by time marching on, something to take his mind off the “difficult” pandemic but also by a family friend who took up French. Learning Welsh was a positive thing. “It’s opened my ears to language in general,” says Stephen. “the connections between different languages are something I find quite interesting.

Moving into his 50s and with the pandemic happening at the same time too, he says: “It really helped me suddenly have a new sort of sense of purpose, at a time when it’d be very easy to just stagnate.”

Purpose and motivation may be something that differs for every learner but remains a key question asked by non-Welsh speakers. To make things a little easier Kierion Lloyd apparently has a standard answer. “Why not?” he says, “why wouldn’t I learn the language of my father’s?”