In China, a growing number of young people in their 20s and 30s are returning to their family home and many of them are being paid to do domestic chores by their parents. How tough is life for these full-time children and what is behind this trend?

Hot oil sizzles in the pan as Gu Liuqi adds minced meat. She then adds pickled beans and crushed red chilli peppers, stir-frying for 10 seconds. Next, she adds soy sauce and other seasonings, cooking everything over high heat. Liuqi, 21, has to prepare dinner for her parents every night, but this isn’t the life she had in mind.

Her recently obtained graduation certificate is displayed on the shelf in the living room. Liuqi graduated in June with a degree in animation. Since entering university, she had expected to work as an animator. However, reality takes a different turn.

“I studied animation at university for years, so I always thought I’d work in this field. I dreamed of working in Chengdu,” she says. “But as the saying goes, the dream is beautiful, but the reality is harsh. I feel there’s a gap between my expectations and reality.”

Gu Liuqi is part of the growing group of full-time children in China. The buzzword “full-time children” emerged in late 2022, referring to a new phenomenon where Chinese young adults, who can’t find a job or feel burnt out due to the overwork culture, return home and are paid by their parents to do household chores.

More struggling Chinese young people are becoming full-time children. A group titled “Full-time Children’s Work Communication Centre” boasts over 4,800 members on Douban, a popular Chinese internet forum . The hashtag “full-time children” has garnered over 4 million views on Xiaohongshu, China’s Instagram.

Liuqi spends her day doing laundry, preparing meals for her parents and doing other household chores. Her parents pay her a salary of 5,000 yuan (531 pounds) a month, a respectable sum in her city.

After clearing away the dinner plates to allow her parents to enjoy a night in front of the television, Liuqi opens her laptop to search for jobs on Boss Zhipin, one of China’s largest online recruitment platforms. She doesn’t hold out much hope of finding anything suitable. “It’s really tough to find the right job,” she says.

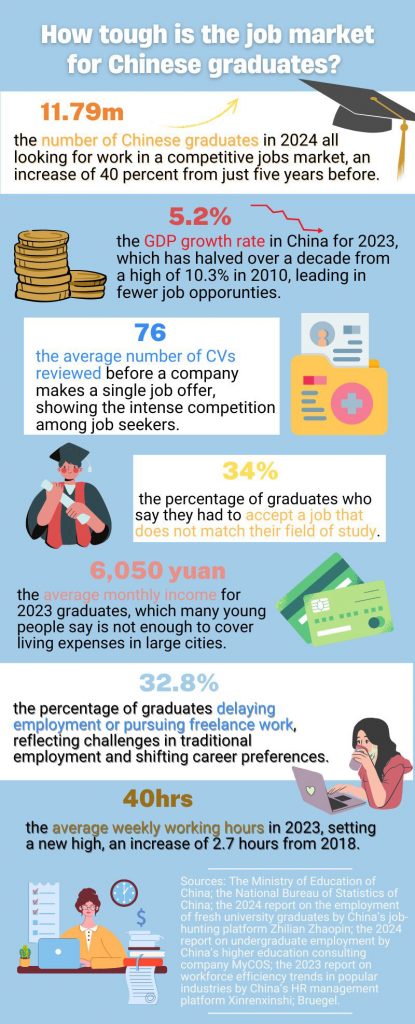

Chinese young people, particularly graduates, face significant employment challenges. The youth unemployment rate has risen since 2018 and hit a record high of 21.3 percent in June 2023 , almost double the pre-pandemic rate . A month later, China even suspended the release of the figure for five months, stating the need for improvements in statistical methods.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, youth unemployment was 14.2 percent in May 2024 using a revised method that excludes students . This is still higher than in other countries, such as Britain , Australia and Japan.

China’s economic slowdown in recent years has significantly impacted employment opportunities. Ka-Ho Mok, a professor from Lingnan University, says Covid has particularly affected China’s economy, making it harder for businesses to create new jobs.

Unemployment is a problem in many countries, but especially in China, according to George Magnus, a research associate at the University of Oxford’s China Centre. “This is mostly due to graduates not being able to find the jobs they want, and there is a mismatch between the skills people have and the jobs available,” he says. “It’s probable also that adult unemployment is higher than official statements say.”

The number of university graduates has been rising due to the expansion of higher education in China, which has intensified competition in the job market, according to Mok. “Two years ago, it was about seven million or eight million. Now, it’s over 10 million. It’s huge,” he says.

Some young people would rather stay at home and exchange housework for wages when traditional job opportunities are scarce. However, not all Chinese young adults facing employment challenges move back home or see staying at home as a permanent solution due to their parents’ expectations.

Chinese parents view staying at home as unacceptable and as a loss of face. They want their children to have decent jobs. Zhang Xiaoying, 22, stayed with her grandparents in their hometown for three months to take a break from the tough job market, but she had to start job hunting because of pressure from her parents.

“My parents don’t accept that I would just stay at home and do housework after so many years of education,” Xiaoying says. “Although they don’t put too much pressure on me to be extremely successful, they still hope I can have a job and earn more money.”

My parents don’t accept that I would just stay at home and do housework after so many years of education

Some full-time children even face conflict at home as their parents feel ashamed of having a jobless child. One young Chinese blogger wrote that during meals, her parents often ask about her plans for the future and compare her to their friends’ children who work at prestigious companies in big cities, which makes her feel pressured.

Many young adults also share that at family gatherings, they often face questions like when they’ll start looking for a job or which city they plan to build their careers in. Relatives often gossip about children’s jobs and incomes. Some full-time children don’t get respect from their families because they don’t meet the traditional definition of success.

Full-time children often clash with their parents over daily habits. One full-time child shared that her dad often argues with her about ordering takeout or sleeping in late. However, she has no other choice as she needs to stay at home to prepare for her graduate school entrance exam. Her post received around 160 comments, with many young people sharing similar experiences.

For some young people, staying at home enhances their bond with their parents instead of causing conflict. Some Chinese parents prioritise their children’s happiness over traditional career expectations. Liuqi’s parents are among them.

They respect Liuqi’s decision to stay at home and are happy to have her with them. “My parents just want me to be happy. As long as I’m happy, that’s enough for them. They don’t pressure me to find a good job,” Liuqi says.

Despite initially feeling anxious about not finding a job, Liuqi has come to enjoy being back with her mum and dad. “While I don’t contribute financially, I provide emotional support for my family,” she says. Tonight, she plans to make spicy boiled beef because she knows it’s one of her mum’s favourite meals.

Some full-time children are recent graduates who want to take time out to prepare for China’s highly competitive civil service exams. Zhao Wenya, a master’s graduate in nursing, feels fortunate to secure a position at a reputable local hospital, as her field isn’t too challenging for job placement. However, her friend, who aims for a government career, isn’t as lucky.

Wenya’s friend travelled around the country on a “test tour”, taking exams in cities from Beijing to Xi’an, but didn’t succeed. Even once, despite topping the written test for a position, she was rejected after the interview.

Wenya’s friend is struggling and feels stressed, often lying awake at night, tossing and turning, and frequently sighing. “She is suffering,” Wenya says. “The last time we talked, she cried, asking, ‘Why can others land a good job right after graduation, but I can’t?’”

To many Chinese parents, becoming a civil servant means having an “iron rice bowl”. Not only is it a decent job, but it also ensures their children are at no risk of unemployment in middle age. Wenya’s friend’s father, a civil servant himself, is keen for her to follow the same path. As a result, she has to stay at home and continue preparing for the next civil service exam.

Now, unlike Wenya’s friend, more young Chinese adults are rejecting the traditional expectations of becoming civil servants. Instead, they pursue careers they are passionate about. Liu Jie, 24, had worked as a freelancer in Guangzhou, the capital of south China’s Guangdong province, after graduation. Recently, she secured a satisfying position at a private company, despite her parents’ desires.

“My parents want me to return to my hometown and take the civil service exam because they see it as a stable job. But I don’t want that,” Jie says. “I think being a civil servant is boring, doing the same monotonous work for decades. I want to pursue a career that offers more freedom, and I don’t want to stay in my hometown.”

Covid has affected many young people’s careers, forcing them to return to their family homes. Li Feifei, 34, who once taught Chinese to foreigners, has been a full-time daughter for three years since losing her job. The language school where she worked had to close due to high rent costs and the lack of international students during extended lockdowns.

When she saw some neighbours working from home or returning to their workplaces while she remained unemployed, Feifei felt uneasy. “During the first few months, I felt extremely anxious and had trouble sleeping. I was in a really bad state,” she says. “I also didn’t know when the pandemic would end. It felt like the world was coming to an end.”

Feifei feels lucky because her family stays by her side, offering financial and emotional support. “My family never complains or blames me. They don’t pressure me. They just said that when the situation improves, I could look for a job, and if not, I could stay at home,” she says.

They just said that when the situation improves, I could look for a job, and if not, I could stay at home

The parents of young people usually have sufficient financial strength to support their children staying at home. “They benefited from the economic and productivity boom that’s no more,” George says.

On Chinese social media, full-time children are often criticised for taking their parents’ money and are labelled “ken lao zu”, which literally means “the group that gnaws on the elderly”. This term, once a popular buzzword, refers to young people freeloading off one’s parents.

Feifei says she is not part of the “ken lao zu”. “‘Ken lao zu’ are like parasites. They lack ambition and live off their parents’ wealth,” she says. “My circumstances are different. Due to the pandemic and the downturn in the teaching industry, I had no other choice.”

Many full-time children also take care of their ageing relatives. Feifei says that in addition to doing household chores, looking after her grandparents is her most important work. In return, her dad gives her 4,000 yuan (about 440 pounds) each month. “Paying me is like hiring a nanny, but at half the cost,” she says. Both Feifei and her dad benefit from this arrangement.

Feifei’s grandfather has diabetes, and her grandmother takes health supplements. Every evening, Feifei sorts their pills into small, colour-coded boxes and labels them with the times they should be taken. The next day, she assists them with their medication, offering them cups of water and placing the pills in their hands.

At mealtime, Feifei supports them one by one as they walk from the bedroom to the dining room. They move slowly, with one hand on the wall for stability and the other arm held by Feifei. At the table, she serves them, placing their favourite dishes onto their plates.

Looking after ageing parents and grandparents is about returning a favour, which is an important part of Chinese piety culture. Feifei says, “When I was young, my father worked in a distant city, so I was raised by my grandparents. I have a deep bond with them. Taking care of my grandparents is my way of repaying their kindness and upbringing.”

For many full-time children, staying at home is a temporary solution, according to Mok. “If the labour market gets better, young people will look for jobs,” he says.

Feifei has noticed more and more foreigners on the streets, whether for study or work, when she takes walks. She feels it is time to return to the workforce. “I plan to start applying for jobs in September,” she says. “I’m about to end my time as a full-time daughter.”

Though most full-time children view the role as a stopgap, others see it as a long-term solution, especially those who have elderly relatives with chronic health conditions. Dai Zhen, 31, quit her job in Shanghai and moved back into the family home to care for her parents last May.

At that time, her father had just undergone surgery for colon cancer, and her mother was dealing with chronic diabetes. Soon after she returned, her father also suffered a stroke and was hospitalised for a week. Although her dad has since recovered and her parents can mostly take care of themselves, Zhen still chose to remain home to support them.

She wants to monitor their health as they grow older. “Aging is an irreversible process, and my parents are getting old every day. Future health issues are also inevitable,” she says. “If my dad’s health isn’t properly managed or if he doesn’t take his medications regularly, there’s a high chance of a stroke recurring. Each recurrence could be more severe, potentially leading to paralysis.”

In addition to tasks like measuring blood pressure, monitoring blood sugar, and sorting medications for her parents, Zhen spends a lot of time with them. Zhen and her parents cherish the moments they spend together.

After dinner, in her family’s courtyard, a shuttlecock flies from her mother’s racket, and Zhen hits it back. She often plays badminton with her parents after dinner. “Rather than saying I’m taking care of them, it’s more like I’m here to keep them company,” Zhen says.

Rather than saying I’m taking care of them, it’s more like I’m here to keep them company.

Life in the hometown for full-time children can seem dull compared to the vibrant urban life in a developed city. Zhen’s weekends and evenings in Shanghai were filled with social activities and cultural experiences. When Zhen first moved back home, she found it hard to adapt to the more monotonous lifestyle.

Though familiar and comforting in its way, her small city lacks the theatres, concerts and malls that she enjoyed in Shanghai for several years. “When I was in Shanghai, I would spend my weekends or free time watching shows or shopping with friends. But there isn’t much of that now,” Zhen says. “There are no friends here, and there are no places for performances or concerts.”

Social interaction is a problem for full-time children, and digital social lives offer a solution. In the evening, after hanging up the clothes from the washing machine, Feifei lies on her bed, opens a group on Douban that interests her and interacts with netizens. She says, “Chatting online is my way to share interesting things and thoughts with others. It also makes me feel less alone.”

Many full-time children don’t give up on their ambitions and regularly send out CVs to secure employment or enhance their skills for better opportunities.

Feifei has been working on enhancing her teaching skills. “Before, I could only teach intermediate Chinese, but now I can teach HSK Level 6 and have become a senior teacher,” she says. “I’m most proud of surpassing my past self. Even though I stay at home, I am gaining valuable skills. This is also preparation for my next job opportunity.”

Being full-time children also gives young people the freedom and time to figure out what they really want to do with their lives, rather than simply settling for a job they don’t like or find unsatisfying. Liuqi considers her role as a waystation and plans to continue her education to enhance her job prospects.

“I still want to work in a field related to my studies, but it appears that a higher degree is required,” Liuqi says. “I plan to take the graduate entrance exam. Over the next few months, I will be preparing for the exam while also spending time with my parents.”